I can't decide whether to frame or burn the receipt from a Chevron filling station in Berkeley, Calif., that documents how much I spent to fill the tank of my 12-year-old Nissan Quest minivan on Sunday morning. At $4.09 a gallon for regular unleaded, the total came to $65.68. That's the most I've ever paid for a tank of gas, so I feel inclined to treat the paper record with respect. But a couple of weeks from now, if recent trends hold true, my unwanted milestone will be eclipsed again, and the receipt transformed into a trigger for nostalgia. Four-dollar-a-gallon gasoline? Ah, those were the days.

On Tuesday gas prices hit record highs in the United States for the 21st day in a row. Many Americans are understandably upset and angry. Partisans on both sides of the political aisle believe they know why this is happening. The left blames greedy, customer-gouging oil companies; the right pillories environmentalists for blocking the construction of new refineries, preventing offshore oil development and opposing drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

But there's much more going on here than good old greed or restrictive environmental regulations. Explaining the high price of gasoline at my local pump requires taking into account surging demand for oil in China and India, the falling value of the dollar, the impact of commodity price speculation by energy traders and a whole constellation of factors exerting steady downward pressure on supply. Those include the Iraq war, political instability in Nigeria and anti-American intransigence in Venezuela and Iran. There's also the ever-popular peak oil thesis: As the production of existing oil fields in Russia, Mexico, the North Sea and possibly Saudi Arabia inexorably declines, discovery and exploitation of new sources of oil are becoming steadily harder and more expensive.

Even the people who have spent their entire lives studying the price of oil don't know for sure how to weigh each factor for responsibility in the total equation. Perhaps the safest thing to say is that it's all in there, in my $65 receipt. Kidnappings of oil executives in Nigeria and the nationalization of Exxon-operated facilities in Venezuela. Chinese economic growth and hedge fund manipulation. ANWR and air quality. The price of gas in the United States is a consequence of global economic growth, rising standards of living, greed, politics and the stresses induced by 6.5 billion people going about their business on a planet with limited resources.

Sound complicated? It most certainly is, which is one reason why we should avoid the temptation to simply blame greedy oil companies or radical environmentalists. But it's also strangely simple -- the world, and its manifold dilemmas, can be seen in a single gallon of California gas. Let's take a closer look.

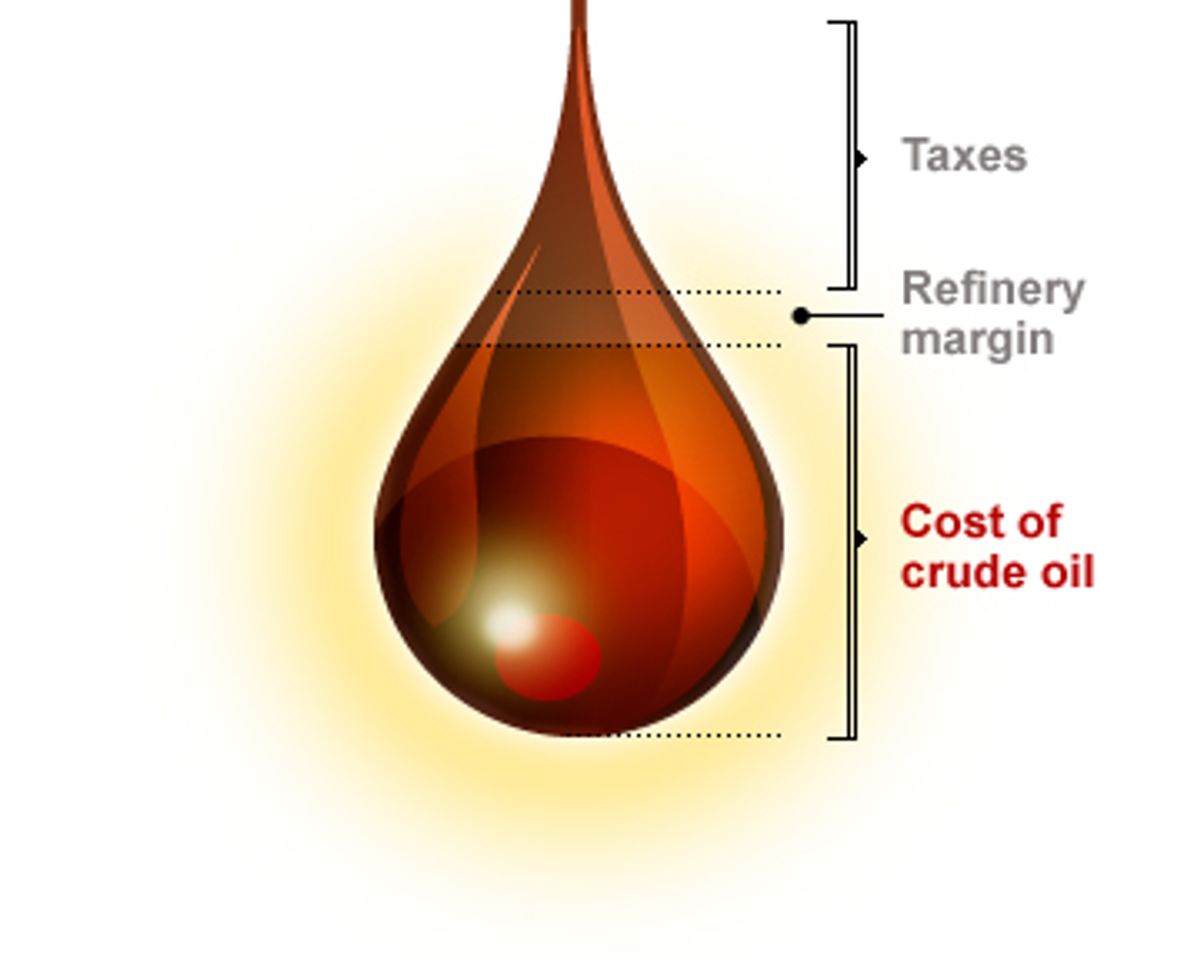

On May 26, the average price of a gallon of regular unleaded gasoline in California was $4.09 (remarkably, exactly what I paid on May 25). A variety of taxes account for 66 cents of that total. The federal government and the state of California both charge separate 18-cent excise taxes. State and local sales taxes account for roughly 29 additional cents. There's also a 1-cent "state underground storage tank" tax that funds the cleanup of groundwater-polluting tanks.

In mid-May, 19 cents of the total price of a gallon of gas in California could be chalked up to the "refinery margin" -- the costs of refining crude oil into gasoline along with the slice of profit extracted by the refinery operator. Over the course of 2008, that number has fluctuated, from a high of 48 cents in late March to the current low. Another nickel or so of the price of each gallon accounts for the "distributor's margin" -- the costs of getting the gasoline from the refinery to the filling station, marketing the gasoline and the profit cut taken by the retail dealer.

The drop in the refinery margin from 48 cents to 19 cents over the last two months suggests that refineries are having trouble passing on the full costs of the most recent increase in crude oil prices to their customers. Refineries are caught in a bind. Even as Californians are cutting back on consumption, the cost of crude is continuing to rise. But if the refineries continue to raise their own prices for gasoline at the same rate that the cost of crude is rising, they run the risk of depressing demand even more.

The disjunction between the enormous profits to be made drilling for oil and the much tougher business of transforming that oil into gasoline and selling it can be confusing, especially when the same company is handling both parts. My gallon of gas was purchased from a Chevron gas station -- which is not surprising, considering that Chevron controls 25 percent of gasoline refinery production in California.

In 2008, Chevron recorded its largest first-quarter profit ever: $5.17 billion. But according to the San Francisco Chronicle, Chevron's profits from refining and selling gasoline in the United States were actually down 99 percent in the first quarter of 2008 from a year earlier, and "during the previous two quarters, the company actually lost money making gas." That $5 billion in profits is derived primarily from extracting the oil out of the ground and selling it on the open market where prices are set.

The relatively small percentage of the price of a gallon of gas that goes toward refinery profit margins pokes some holes in the notion that environmental regulations -- at least as applied to refineries -- are a primary villain in inflicting high gas prices on the public. According to this theory, which seems to get more media time with every nickel jump in the price of a gallon of gas, "extremist" air quality regulations combined with legal harassment by environmental activists have inhibited refinery owners from building new refineries.

Central to this proposition is the idea that the real bottleneck for gas prices is not in the supply of oil, but in the ability to process it and refine the oil into gasoline. An example of how this works came after Hurricane Katrina, when numerous refineries in the Gulf Coast region were knocked out of commission, and the price of gas spiked because the remaining refineries couldn't make up the difference. If environmentalists hadn't prevented new refineries from being built, argued the critics, there would have been enough slack in the system to avoid such oil shocks.

It is true that no new refineries have been built in the United States since 1976 and hundreds have closed down. Between 1985 and 1995, laments the California Energy Commission, 10 refineries closed in California alone. It is also true that overall refining capacity is down, in both California and the entire United States. But total production of gasoline is up, nearly 20 percent, since 1976. Instead of building big new refineries, refinery owners closed smaller, inefficient -- unprofitable -- facilities and expanded and improved the production lines at their existing complexes.

So, sure, environmental regulations have added to bottom-line costs, but they have by no means crippled the industry -- and anyone who has ever lived downwind of a refinery complex is probably deeply grateful for the restrictions that make the air breathable. In fact, at least one study of California refineries in the Los Angeles area found that even though environmental regulation compliance costs rose significantly, overall productivity rose faster at the refineries that were forced to upgrade than at refineries not subject to comparable environmental regulations.

To understand why California gas prices are historically above the national average, the likely explanation isn't environmental restrictions on refinery operations, but the reality that California's strict air quality regulations require a special blend of gasoline that only a few refineries outside of California are capable of producing. So when demand spikes in California, or a disaster (or simple maintenance overhaul) takes out even just one refinery complex for any extended period of time, prices rise quickly across the state because supply can't easily be found to replace the lost production.

This problem is not unique to California. The U.S. gasoline market features scores of different blends of gasoline mandated for different regions. Blends vary within states, according to seasonal change and depending on local wild-card factors such as state mandates for ethanol content. It's a crazy-quilt system that is fundamentally inefficient because refineries optimized to produce the blends required in one region cannot quickly turn around and make up for shortfalls experienced in other regions. It also plays to the advantage of local refineries by limiting their competition -- a Government Accountability Office study asserted that California gas prices were 7 cents higher than the national average for this very reason.

The federal government could eliminate such madness with a stroke of a pen. It could mandate that all gasoline adhere to some uniform fuel standard. But depending on where the line was drawn, as economist and oil price expert James Hamilton notes, such a move would likely raise pollution in some areas and costs in others -- ruffling feathers all across the country. It would also work against the interests of refinery operators, who benefit from not having to face full competition in their protected districts.

But questions about refinery capacity, environmental regulations and Balkanization of the overall market shrivel when compared with the real force responsible for the dramatic rise in gas prices over the past eight years. Far and away, the largest factor contributing to the total price of a gallon of gasoline in California (and anywhere else in the United States) is the cost of crude oil.

As of 2005, about 40 percent of Californian gasoline is derived from in-state wells, 40 percent comes from foreign sources, and 20 percent comes from Alaska. The California Energy Commission uses the price of Alaskan North Slope crude oil as the benchmark for calculating its breakdown of gas prices. On May 19, it pegged Alaskan North Slope oil at $3.03 per gallon of gasoline -- or about 75 percent of the price Californians pay at the pump.

As for any other grade of oil, the price of Alaskan North Slope is set on the open global market, according to what bidders are willing to pay for it. Such bidders include traders who are merely hoping to cash in on steady price appreciation, but also include anybody who actually needs to take physical ownership of the product for whatever purpose. This is one reason why accusing oil companies such as Exxon and Chevron of gouging the consumer misses the point. Exxon doesn't set the price of crude oil, nor does it unilaterally set the price of gasoline at the pump. Those prices are set by what buyers -- refineries, industrial complexes, distributors -- are willing to pay. And for years now, buyers have outnumbered sellers.

According to the California Energy Commission, "for every one dollar increase of the cost of a barrel of crude oil, there is an average increase of about 2.5-cents per gallon of gasoline." In 2000, the price of a barrel of crude was about $25; in May 2008, $133. You can do the math.

Just as there are manifold reasons explaining why global demand is currently growing faster than supply, there are a variety of things that governments could do to assuage the problem. Some would make absolutely no long-term difference (and could even contribute to higher prices by boosting short-term demand), such as the gas tax holiday proposed by John McCain and Hillary Clinton. Others could chip away at pieces of the problem: We'd know a lot more about the role of speculation in setting prices if the electronic exchanges that currently don't have to report trading activity to the government were properly regulated.

It seems reasonable to assume that the price of oil will rise to a point at which even the seemingly bottomless appetite of China begins to slake. At that juncture, we could see a massive bubble pop, as traders scramble to unload their futures positions. But it also seems increasingly likely that the world has reached that critical point at which it is simply impossible to find and develop new sources of cheap oil to replace what we have already discovered and are daily consuming.

In that case, price will be the ultimate regulator of both the market and consumer behavior. A few years back, when crude oil and gasoline prices were just getting started on their historic run-up, American driving habits failed to change much in response, and we heard that demand for gasoline was what economists like to call "inelastic." In other words, our willingness to consume wouldn't stretch up or down as prices fluctuated. People had to drive to work or to the grocery store or to the kids soccer tournament. So we filled our tanks and cut back on the fine dining.

But the drumbeat of record gas prices has changed that equation. We now realize that we just hadn't reached the proper price point necessary to make a real difference in our behavior. Today, Americans are driving billions of fewer miles than they did a year ago. Sales of fuel-efficient cars are surging and the price for a used Ford Expedition is plummeting because the market is glutted by SUV owners desperate to unload their gas guzzlers. It's clear that millions of Americans, just like me, are staring gape-mouthed at their filling station receipts and thinking, “There's gotta be a better way.”

And there is. But it's not likely to come about by political attempts to twist OPEC's arm or legislating lower prices. Nor can (or should) Americans try to stop Chinese or Indians from buying new cars and installing air conditioning. Instead of striving to remake the world so it gives us cheaper gas, maybe we should listen to what the price of a gallon of gas is trying to tell us: Use less.

Shares