In the past quarter-century, there has probably never been a better time for a presidential candidate to charge into downtown Manhattan and make a speech arguing for more regulation of the financial industry. The moral authority of market fundamentalism (if such a thing ever existed) is in tatters, and even Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson, the former CEO of Wall Street's crown jewel, Goldman-Sachs, is acknowledging that new rules are necessary to clean up the current mess.

So for liberal critics of capitalism as currently practiced in the United States, there was much to admire and appreciate in Barack Obama's speech Thursday morning at Cooper Union in New York. The address provided yet another example of what the senator from Illinois does best: It was an eloquent, nuanced, smart defense of the pressing need to roll back decades of government irresponsibility and ensure that the interests of, as he put it, "Main Street and Wall Street" are better aligned.

"Our free market was never meant to be a free license to take whatever you can get, however you can get it," said Obama. He reached all the way back to the first secretary of the treasury, Alexander Hamilton, in his effort to argue from first principles that government has the right and responsibility to intervene in the economy to ensure that the few do not benefit at the expense of the many. He referenced the 1999 repeal of the provision in the Glass-Steagall Act that previously separated commercial and investment banking. He even declared that it was "time to realign incentives and compensation packages, so that both high level executives and employees better serve the interests of shareholders" -- a broadside unlikely to win him a lot of votes in downtown Manhattan (or at the fundraiser at the investment bank Credit-Suisse that Obama headed to after his speech, as was helpfully pointed out by the Clinton campaign).

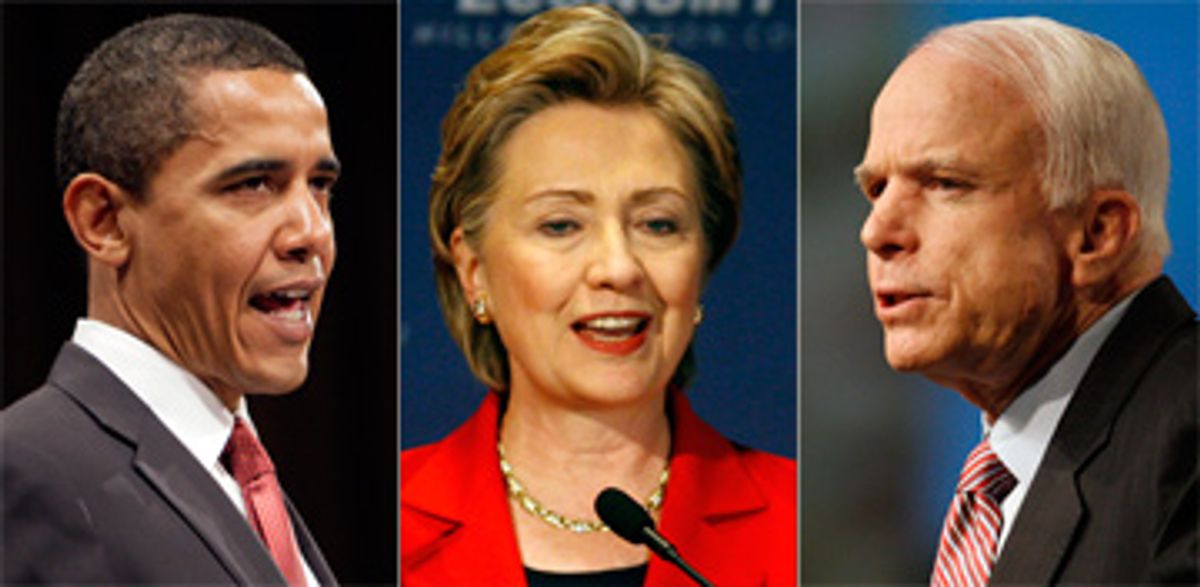

The comparison with Sen. John McCain's speech on Tuesday could not be more stark. Obama's jibe -- that McCain's "plan ... amounts to little more than watching this crisis happen," is not off the mark. McCain took great pains to stress his intent to intervene in the workings of Wall Street as minimally as possible. For those deluded souls who might still think there is no significant difference between the two major parties in the United States, a review of McCain's and Obama's speeches this week is in order. They are like bookends at opposite ends of the economics shelf. Obama snuggles up to John Maynard Keynes, while McCain seeks the warm embrace of Milton Friedman. Obama sounded like he understood what he was talking about. McCain sounded like he was reading a speech designed to make him look like he understood what was going on.

Which raises an obvious follow-up: Where does Hillary Clinton fit in? Obama did not mention Clinton in his speech. He drew no distinctions between his policy platform and hers. In part, this is understandable: The differences between Clinton and Obama are far smaller than the differences between either candidate and McCain. They both support Sen. Dodd's proposal to give mortgage lenders an incentive to buy out or refinance existing mortgages. Both support direct help to stressed homeowners and communities. Both support changes to the bankruptcy laws.

Obama does not support a five-year mortgage interest freeze or a moratorium on foreclosures -- two prominent planks of Clinton's economic agenda. One could make the argument, therefore, that Obama's approach is less far-reaching than Clinton's, or, conversely, one could argue that Clinton's wilder promises are politically unrealistic, even with a congressional majority. But the clearest difference between the two speeches is this: Hillary went to Philadelphia and promised Pennsylvania voters a gift basket of direct government assistance. Obama went to New York and made a case for long-term, fundamental change, along with a smaller gift basket.

How does that play out politically? Do working-class Pennsylvania voters care what Alexander Hamilton thought about government's role "in advancing our common prosperity" or how the repeal of Glass-Steagall plays into Wall Street's current troubles? That seems unlikely -- and the Clinton campaign was quick to seize upon that point, claiming in a press release that in his speech "Senator Obama announced a series of broad, vague principles, while offering no new concrete solutions to provide Americans with greater confidence in the market or keep them in their homes."

To which one could respond, back in 1980, Ronald Reagan announced a series of broad, vague principles, and then proceeded to drastically change the direction of American politics and economics. If we take both Clinton and Obama at their word, we have Clinton promising a boatload of quick fixes, and Obama promising a profound change of course. What unites them, in opposition to McCain, is that both understand that the U.S. is facing a real problem.

Shares