In the spring of 1989, the fax machine was China's Twitter -- the miracle technology connecting Chinese democracy activists with each other and the outside world. In Berkeley, Calif., the apartment of one Chinese expat student who owned a fax became a 24/7 information clearinghouse. Documents produced by students camping out on the square would emerge magically from the machine in all their subversive glory.

It wasn't as sexy as a YouTube video seconds removed from someone's cellphone, but for China-watchers accustomed to gleaning everything they knew about current events in the People's Republic from the reports of a New York Times or Washington Post foreign correspondent, it was as if a magnificent firehose had been turned on. Years before the Internet exploded into mainstream consciousness, we made grandiose declarations to each other about how advances in communications technology were breaking the tyrannical hold that authoritarian governments had over their citizens. Life in the PRC would never be the same, we knew.

I say "we" because I, like the thousands of Chinese expats in the Bay Area and elsewhere, was living and dying on the daily news from Beijing with almost unbearable intensity. I was a graduate student in the Journalism and Asian Studies programs at U.C. Berkeley, I spoke Chinese, and I'd been studying China for almost 10 years. I had toured the mainland in 1984 and 1986. I was writing a thesis on freedom of the press in post-martial law Taiwan, and I believed I could see in the mainland what had previously happened in South Korea and Taiwan -- economic growth was mobilizing the middle class to demand greater freedom. No one had expected something like this to happen so quickly after Deng Xiaoping's economic reforms, but the pictures on CNN could not lie. Change was in the air.

It was a giddy time. The power of totalitarian communist governments seemed to be disintegrating everywhere. I did not have Andrew Sullivan collecting every last YouTube video and tweet from Beijing on a minute-by-minute basis, but I hung on cable news reports with exactly the same strain of desperate exuberance. Something incredible was happening. China would never be the same. We were witnessing one of the fulcrum moments of history.

If there's one career move I regret most in my life, it is that I didn't drop out of U.C. Berkeley that spring and head directly to Beijing and report for myself what was happening, without the intermediation of any technology other than my glasses. Instead, I decided to wait until the end of the school term. I had tickets booked for June 6.

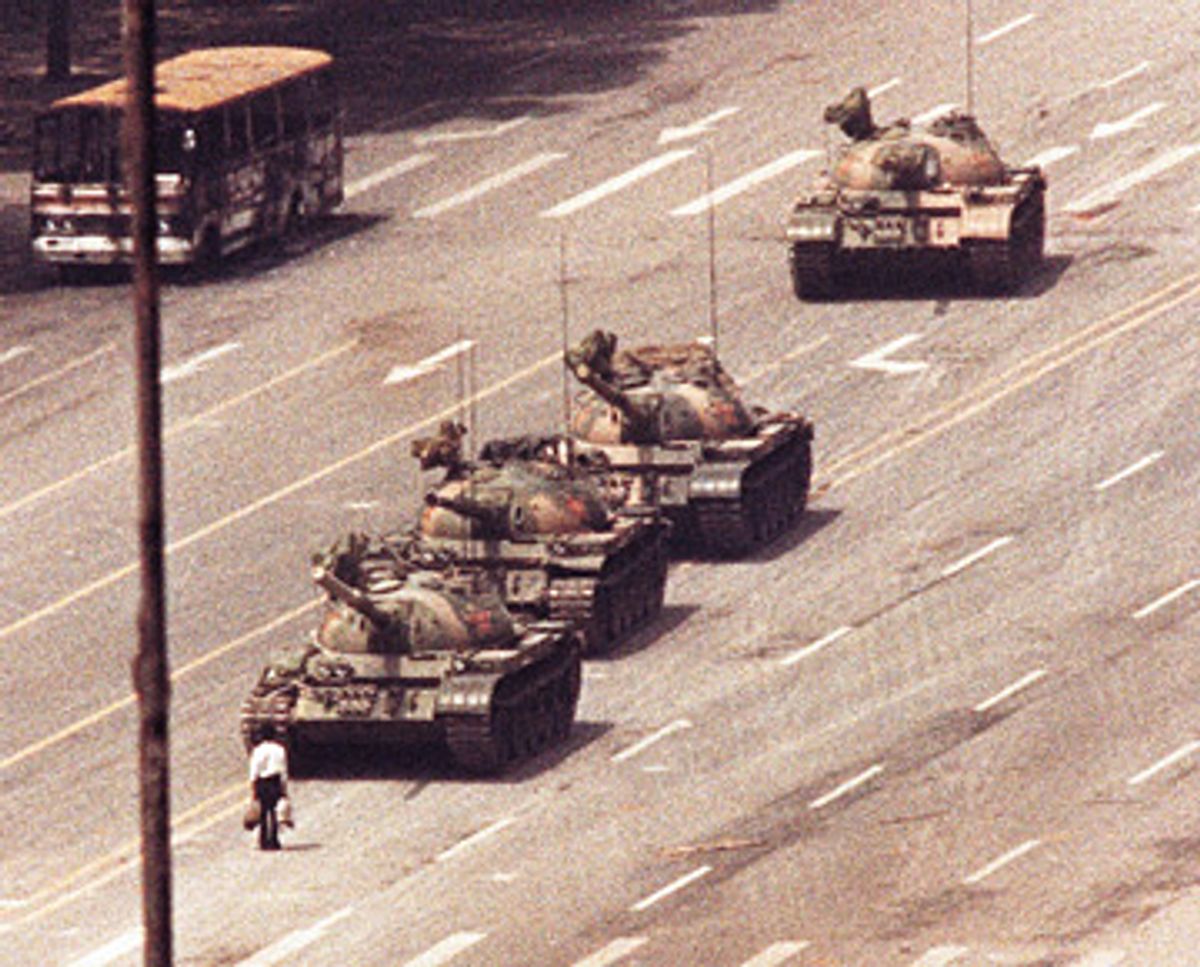

We all know how the endgame played out at Tiananmen on June 4, but I'm not so sure everyone has truly internalized the awful lessons. As I've been reading coverage of the events in Iran all week long, I've been feeling increasingly sick to my stomach. There will be no Velvet Revolution here. When a government is willing and able to use murderous force against its own people, all the good will and giddy excitement and Internet access in the world is as so much dust.

And so, the tweets from Tehran are breaking my heart. Because who can doubt that Ayatollah Khamenei and President Ahmadinejad have the same iron resolve to maintain power as Deng Xiaoping did in 1989?

This morning's tweets recognize that. "The situation in Iran is now CRITICAL -- the nation is heartbroken -- suppression is imminent," reads one. "Can you believe what Khamenei said?! I feel sick to my bones ... and the people listening to him and shouting slogans; THINK," reads another. After the declaration at the Friday prayers by Iran's supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, that there was no rigging in the election and Mahmoud Ahmadinejad had won a "definitive victory," the writing is on the wall for all to see. A hard-line regime has taken a hard-line stance, and blood can be the only outcome.

Even the most passionate of Iran protest chroniclers, Andrew Sullivan, could not miss the ominous portents embedded in Khamenei's speech, but even so, he is still hanging on to a sense of hope that reminds me far too much of how I felt in the spring of 1989 (minus the religious posturing).

I fear deeply what is about to happen. But I also sense that the Gandhi-strategy of the majority is a winning one. If they can sustain their numbers and withstand the nightly raids, and if they can overwhelm the capital tomorrow in another peaceful show of strength, then they can win. And the world will change. This is their struggle now, requiring the kind of courage that only God can provide. Their God, my God, the God of the Torah and the Koran and the Gospels.

Something is happening in Iran.

Yes, we thought the same thing before the tanks rolled in in 1989. And then we realized that a mass movement melts away when the rulers are determined to open fire. And whether your weapon of choice is a fax machine or a re-tweet, there's not a whole lot you can do.

Shares