The specter of 1937 is haunting the world again. Today's installment comes from The New York Times' David Leonhardt, who warns that the global decision to cut government spending and tighten the austerity belt runs a very real risk of cutting short a shaky economic recovery -- a repeat of the events the occurred in the United States 73 years ago.

Wednesday morning's U.S. job numbers underline the danger. The ADP private sector job report counted only 13,000 new jobs in June, coming in considerably below the consensus economist forecast of a 60,000 increase. A sharp drop in Census hires means Friday's non-farm labor report from the government is already bound to produce a topline negative number, but now the worry is that the underlying trend for non-Census hiring may be pointed in the wrong direction. And the U.S. government, which can't even get an extension in unemployment benefits passed, appears powerless to do anything.

(Leonhardt reports that even Goldman-Sachs economists are calling the Senate's inability to function "an increasingly important risk to growth.")

The irony here is that the initial global response to the financial crisis and worldwide recession demonstrated that politicians and central bankers had learned the lessons of the Great Depression. World leaders executed an effective strategy of coordinated fiscal stimulus and expansionary monetary policy. A lapse into depression, for the nonce, was averted. But now they're reverting to their old bad habits.

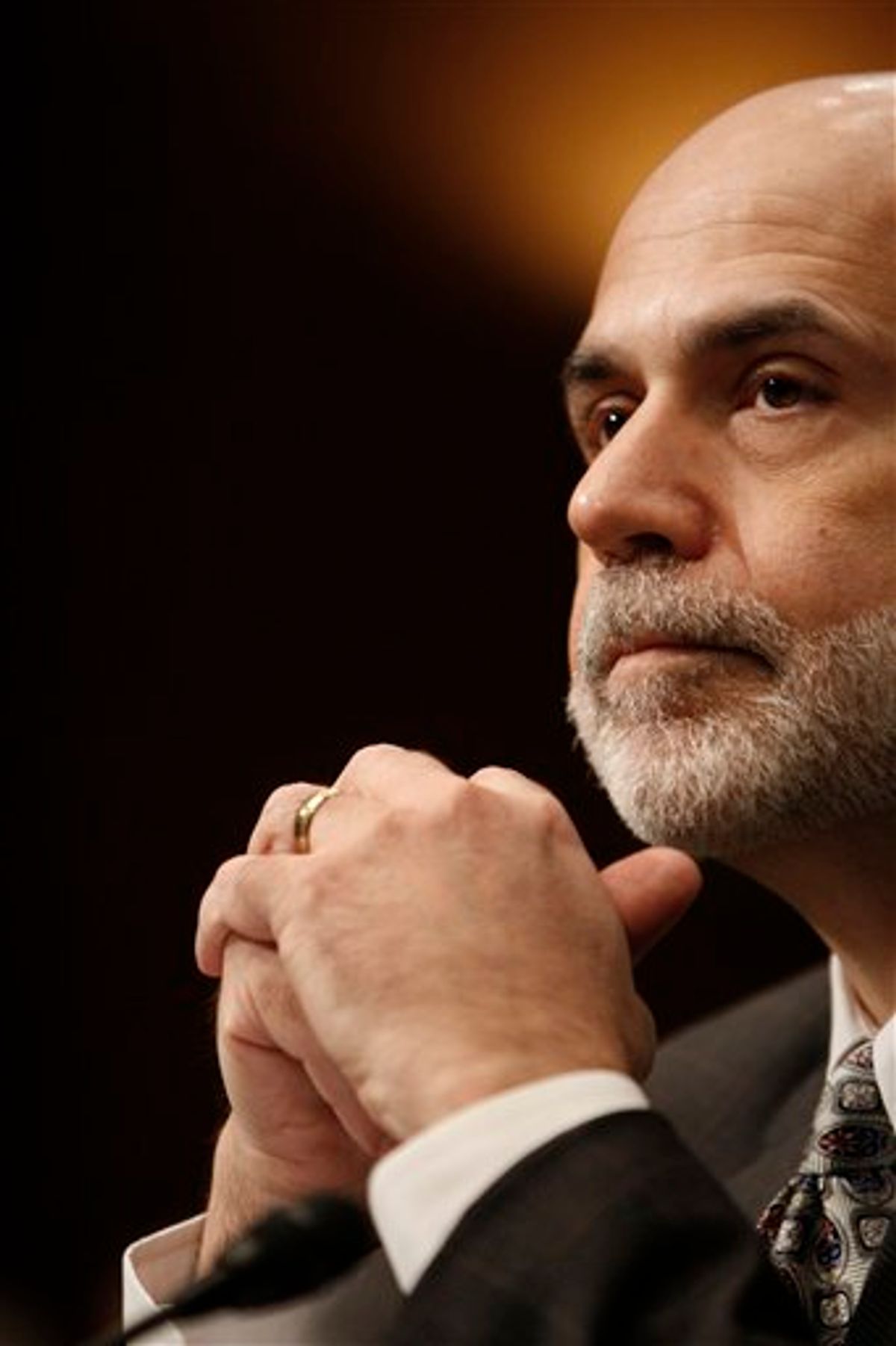

Or are they? Tyler Cowen argues this morning that not enough attention is being paid to monetary policy. In 1937, he argues, "monetary policy was not just insufficiently expansionary, it was absolutely draconian. " And since the main selling point for Ben Bernanke's tenure at the Fed is that he is supposed to be one of the greatest living experts on monetary policy and the Great Depression, there's no way he too will repeat the mistakes of 1937, right?

"If monetary policy is sufficiently accommodative, I do not see that we are risking a 1937-8 repeat," writes Cowen. There's still time to drop money from helicopters.

But in a real head-scratcher, to help illustrate his point, Cowen links to two pieces of analysis that both argue that Bernanke has already repeated the monetary policy of mistakes of 1937.

David Beckworth and Scott Sumner both point to the Fed's decision in 2008 to start paying interest rates on "excess reserves" as functionally equivalent to the Fed's decision in 1937 to increase reserve requirements. In both cases, the result is that banks are encouraged to sit on more cash, rather than put the money to work by lending it out.

The only ray of hope here? If the Fed really is pursuing an effectively contractionary economic policy, Ben Bernanke has the power to change course at a moment's notice. And the U.S. Senate can't do a damn thing to stop him.

Shares