Can't get enough of those rare earth elements! David Cay Johnston, former New York Times reporter and ace exposer of tax law shenanigans, writes in to remind HTWW that chapter four of his book, "Free Lunch: How the Wealthiest Americans Enrich Themselves at Government Expense (And Stick You With The Bill)," includes the interesting, if disturbing, story about how China ended up with a monopoly on the neodymium-boron magnet industry.

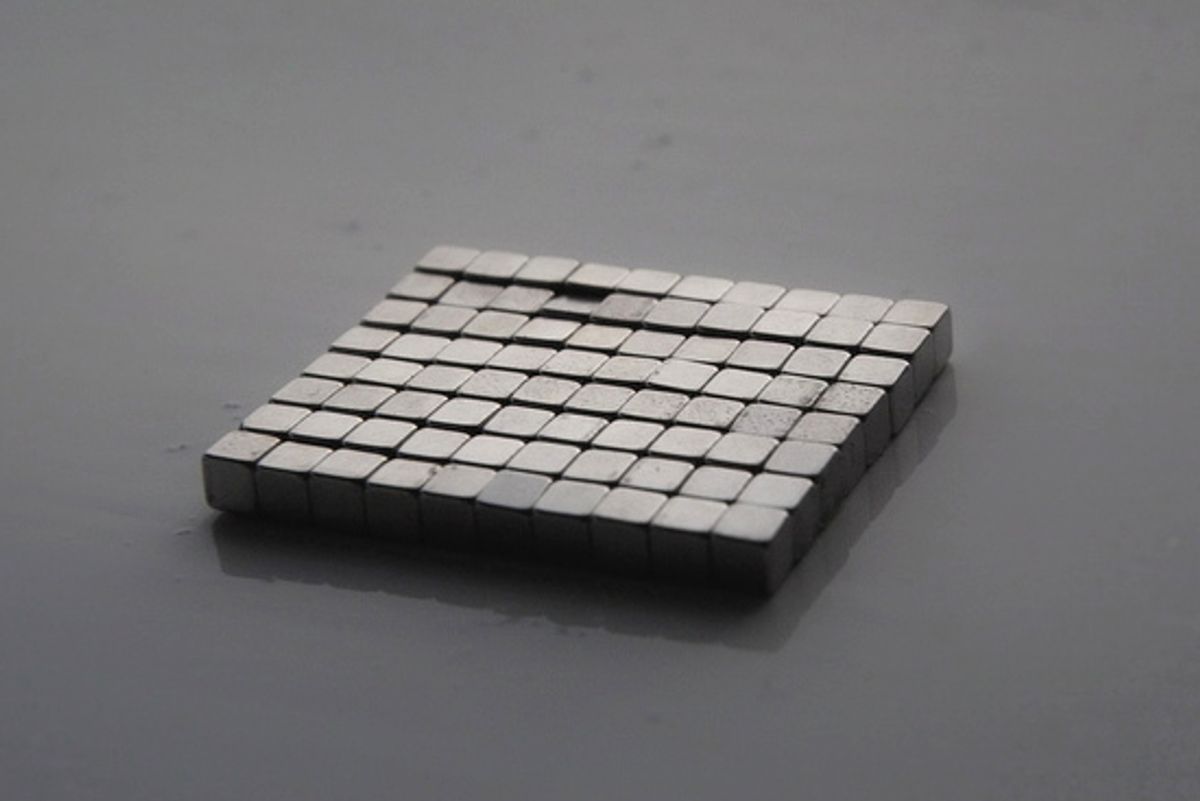

(Readers will recall that neodymium is one of the rare earth elements that the United States no longer has the capacity to process. Neodymium magnets are used in computer hard drives, smart bombs, wind turbines, and hybrid car engines.)

Once upon a time, the U.S. did make neodymium magnets. A subsidiary of General Motors called Magnequench pumped them out, and employed 260 people to do so.

Then in 1995 the automaker decided to sell the division. Because the deal was for only $70 million it attracted little attention. The buyer was a consortium of three firms led by the Sextant Group, an investment company whose principal was Archibald Cox Jr., the son of the Watergate special prosecutor whom President Richard M. Nixon famously fired.

In the few press reports Sextant got most of the notice, but the real parties behind the purchase were a pair of Chinese companies -- San Huan New Material High-Tech Inc. and China National Nonferrous Metals. Both firms were partly owned by the Chinese government. The heads of these two Chinese companies are the husbands of the first and second daughters of Deng Xiaoping, then the paramount leader of China.

Johnson portrays the deal as a quid pro quo. General Motors wanted access to the domestic Chinese auto market, while China wanted to get its hands on militarily significant technology. The new owners were originally required to keep magnet production and technology in the United States for five years after the deal closed, but shortly after the term expired, the U.S. facilities were closed. Now China has an effective monopoly on the production of the raw ore from which neodymium is derived, the processing technologies that produce neodymium, and the manufacturing of neodymium magnets.

Johnston uses this tale as a launching point for how U.S. tax law encourages American corporations to offshore jobs and manufacturing production. HTWW supports vigorous international trade, but Johnston's reporting on how U.S. companies have manipulated tax laws to increase their own profits at the expense of American workers and the U.S. manufacturing base is appalling. And while the nepotistic corruption hinted at by the presence of Deng Xiaoping's family in an immensely important strategic sector of the Chinese economy definitely should give pause to anyone who thinks economic growth in China will lead to more openness, its hard to avoid the conclusion that the Chinese are playing the game of capitalism a lot more adroitly than the U.S.

Shares