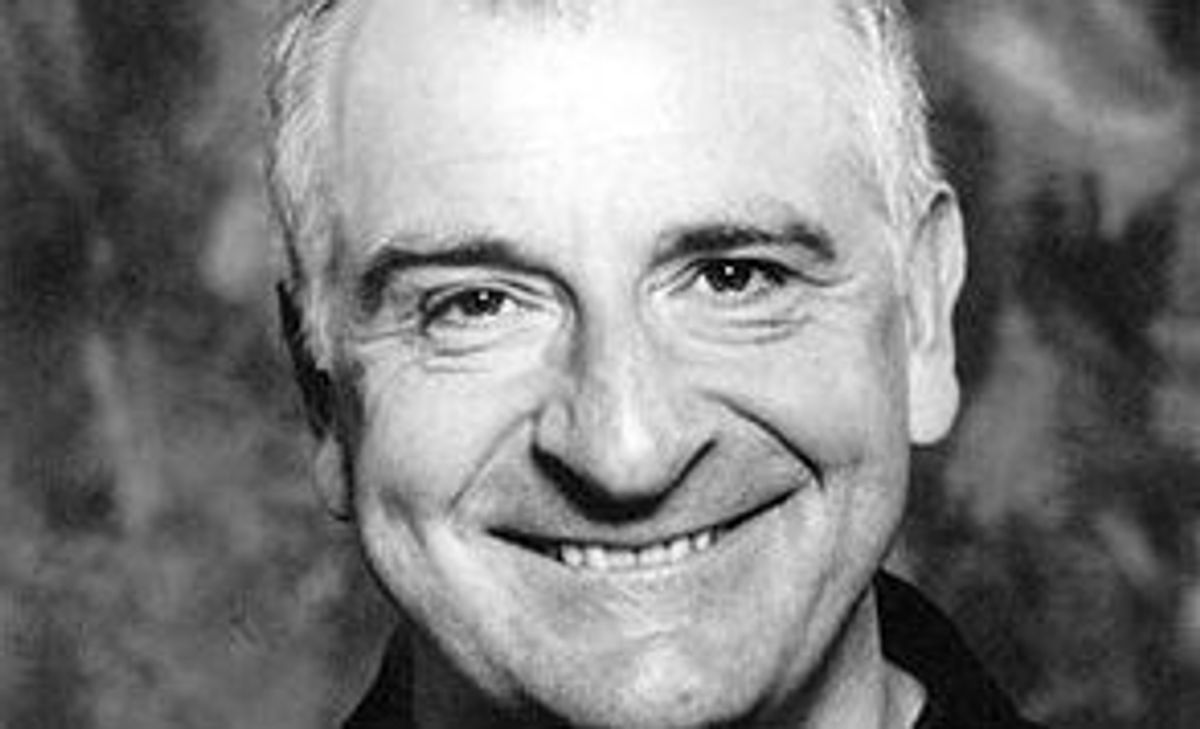

As soon as the news began to spread that author Douglas Adams had died Friday from a sudden heart attack at age 49, tributes to the science fiction humorist began to blossom all across the Internet. There has always been a strong correlation between computer geekdom and science fiction, so it's not that big of a surprise that the author of "The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy" would be remembered fondly online. But Adams was more than just a science fiction satirist -- he was also passionate about technology in the here and now, a geek's geek who was paying close attention to current developments even as he focused his fiction as far ahead as the end of the universe.

On April 10, I had the chance to attend one of Adams' last appearances, when he gave the keynote address for an embedded systems conference at San Francisco's Moscone Center. He was clearly chosen because he knew how to appeal to geek sympathies, and he didn't disappoint. Addressing a packed audience of more than 1,000 while standing in front of a black curtain speckled with twinkling white lights and models of Earth and Saturn, he delivered a speech filled with visions for the future, as well as eloquent defenses of both micropayments and peer-to-peer networking.

Adams drew applause from the audience when he said record companies were fighting the Napster file-trading program to protect a business model being rendered obsolete by technological advances. Napster users were building a peer-to-peer distribution network, downloading and uploading music files among themselves, but for all we know, Adams pointed out, they might have been willing to pay, given a chance. "Until we have digital micropayments," said Adams, "I'm not sure we have the right to call these people thieves."

Micropayment technology would enable vendors of intellectual property to charge fractions of a cent for individual uses. "Piracy would be pointless at those prices," said Adams. He also confessed a grudging calculation he had performed when fans told him they'd read his book 10 times. "Yeah, but you only paid for it once."

Adams' focus on the unrealized promise of micropayments was a subtheme in a much larger message: the tendency of civilizations to be baffled by new technologies.

"Anything that's invented after you're 35 is against the natural order of things," said Adams. The very young, in contrast, aren't even aware of a natural order that's supposedly being violated. "Anything that's in the world when you're born is considered ordinary and normal." He illustrated his point with a story from his own family. When Adams eavesdropped on his 6-year-old daughter pushing her doll's baby carriage, she was mimicking the satellite navigation system in her father's car.

Future technological developments would no doubt be more baffling than ever before, he said. Adams dazzled the audience with a vision of a world where information devices are ultimately "as plentiful as chairs."

"We are participating in a 3.5 billion-year program to turn dumb matter into smart matter," said Adams. When the devices of the world were networked together, they could create a "soft earth" -- a shared software model of the world assembled from all the bits of data. Communicating in real time, the soft earth would be alive and developing -- and with the right instruments, humankind could just as easily tap into a soft solar system. Think of it: a peer-to-peer networked universe!

After the keynote, Adams worked his way through the auditorium for a book signing and drew a small cluster of fans. He cheerfully answered questions, and when I reached him he agreed to answer questions I e-mailed him about mobile technologies. True to his word, he shared his thoughts on hand-held systems, saying they hadn't lived up to his expectations. The last PDA he'd really liked was the Newton.

But I noticed how his theme subtly changed through the presentation, from the curmudgeonly "Technology is our word for stuff that doesn't work yet" to a more visionary pronouncement: "Technology is our word for stuff we don't understand." Adams pointed out that originally the telephone was envisioned as a device for alerting someone that you'd sent him a telegram. The role of the personal computer was also muddled as it progressed in its early days from adding machine to typewriter.

Ultimately Adams' central message was that the only viable approach to surviving in the technological age is an open mind and some common sense -- and he illustrated the message with a complicated anecdote from April 1976. He'd placed a package of cookies and a newspaper on the table in a Cambridge railroad station, across from another traveler. The mysterious stranger had reached across, opened the bag of cookies and started to eat them. There was obvious confusion over the cookies' ownership, Adams remembered. "I did what any red-blooded Englishman would do," he said. "I ignored it." Both men exchanged meaningful glances as they alternately removed cookies from the bag, and it was only when the stranger left that Adams realized what had happened. Adams had placed his newspaper over his own bag of cookies and had actually been eating from the stranger's bag.

Somewhere in England there was now another man telling the exact same story, Adams quipped, "except he doesn't know the punch line."

That story has been borrowed and retold by other inspirational speakers unaware of its origins, Adams pointed out, but he drew a much grander conclusion.

"The world is controlled in a top-down way by large hierarchies that have control over us." The networked computers he'd envisioned promised "a bottom-up world," and it would bring revolutionary changes.

World and industry leaders would do well to keep in mind the evolving new perspectives, Adams concluded.

"Otherwise, you'll wonder why it seems that someone else is eating your cookies."

Shares