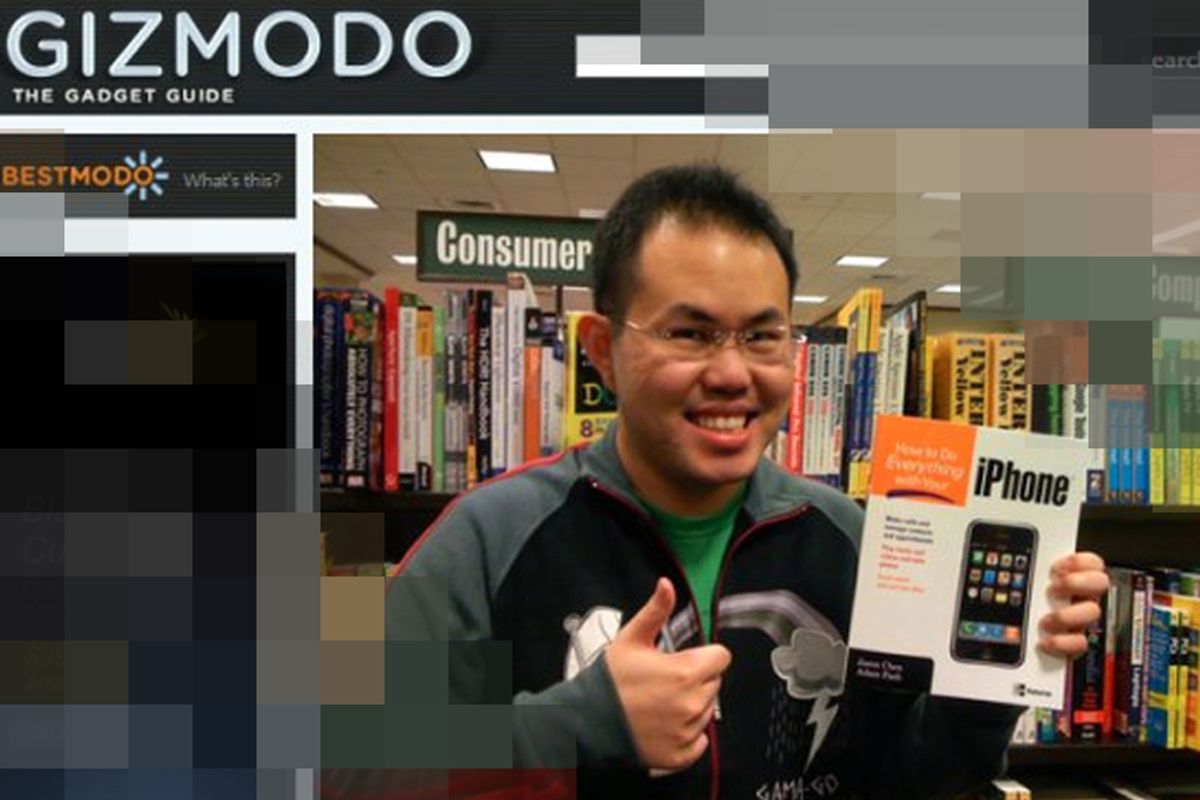

Finally, the world of new media has its own version of the Pentagon Papers. The enthralling lost-in-a-bar-iPhone-prototype saga took a dramatic turn Friday night, after a special task force of Silicon Valley police busted into the home of Gizmodo editor Jason Chen and seized a laundry list of computers, documents and other electronic devices.

Last Monday, the gadget-news site Gizmodo riveted the attention of the tech world by exposing the details of a next-generation iPhone that had been carelessly left in a Redwood City, Calif., bar by an Apple employee. Gizmodo, part of the Gawker new media blogging empire, admitted that it had paid $5,000 to the finder of the iPhone for access to the device. Gawker also revealed the name of the Apple employee who had lost the iPhone, but kept secret the identity of the seller. After Apple lawyers sent a no-nonsense letter to the news organization, Gawker agreed to return the device, albeit only after generating millions of page views for its scoop.

Four days later, on Friday evening, the Rapid Enforcement Allied Computer Team launched into action. Terrorists can waltz into New York City with pounds of explosives loaded in the trunk of their car, but in Silicon Valley, you mess with Steve Jobs and you are going to get an unfriendly visit from The Man. Maybe Mr. Jobs should be appointed the next head of Homeland Security?

Granted, we all knew Jobs was an all-powerful despot worshipped by a fanatic cult and capable of extraordinary feats of techno-magic. But the fact that he can twitch his fingers and send local police smashing through the locked doors of a private citizen's home gives one pause. Apple fanboys are cheering him on, and a noxious aura of sleaziness surrounds the entire "lost" iPhone saga, but any serious journalist who makes a living reporting on anything Apple-related is likely to be feeling a tad nervous about the news. Isn't getting a scoop, by any means necessary, part of our job description? What if a Salon reporter paid money for documents proving the maltreatment of Chinese workers in Apple's offshore iPhone assembly plants -- and then came home to find police rifling through his or her computer?

Of course, that's exactly the point. A lost iPhone, which everybody knew or should have known belonged to Apple, is not morally equivalent to an abused worker -- even if an exhaustive breakdown of its technical specifications will generate umpty-zillion page views. But to Gawker, which has made a habit of thumbing its nose at staid, boring old media, First Amendment principles are now suddenly sacrosanct. Paging Jason Chen: White courtesy telephone, Daniel Ellsberg is calling!

Gizmodo's COO, Gaby Darbyshire, immediately condemned the seizure of the computers and other devices as illegal under California law. Darbyshire cited Section 1524(g) of the California Penal Code, which states that a search warrant may not be served for "any items or items" covered by Section 1070 of California's evidence code, which in turn states: (italics mine)

a) A publisher, editor, reporter, or other person connected with or employed upon a newspaper, magazine, or other periodical publication, or by a press association or wire service, or any person who has been so connected or employed, cannot be adjudged in contempt by a judicial, legislative, administrative body, or any other body having the power to issue subpoenas, for refusing to disclose, in any proceeding as defined in Section 901, the source of any information procured while so connected or employed for publication in a newspaper, magazine or other periodical publication, or for refusing to disclose any unpublished information obtained or prepared in gathering, receiving or processing of information for communication to the public.

It will be interesting to see what a judge thinks of such an argument. Protecting the right of a journalist to protect a source is a non-trivial bulwark of a free society. But does someone who pays cash for a consumer product that could technically be considered a stolen good deserve the special legal protection normally granted to reporters? Just because someone found a lost iPhone doesn't give that person the automatic right to sell it to Gawker -- under California law it may even make Gawker guilty of theft.

And whatever happened to a simple subpoena? Did the Rapid Enforcement Allied Computer Team really have to break Jason Chen's door down? (And why aren't they busy fighting Russian and Chinese hackers, anyway?)

No one ends up looking good in this mess. Steve Jobs is a control freak with police powers. Apple employees don't know how to take care of super-secret prototypes! Finders of lost iPhones are perfectly happy to sell them to on-the-make media outlets. And the pursuit of the page-view jackpot turns reporters into black market entrepreneurs. It's a wonderful world.

But in the final analysis, I guess there's no question that this is "news." Heck, if you concede that the smartphone market is crucially important to the future of media, banking and democracy simply because phones are bound to be the nexus point for connecting everybody to everything in the not-so-distant future, then a first look at the next Apple iPhone is about the newsiest thing a gadget reporter could pull off. And it would be wrong if Gawker's habitual smirking snark or National Enquirer-style fast-and-loose checkbook journalism obscured our right to inform ourselves about what's important.

Shares