During rainy season, Dharamsala, India, home to the exiled Tibetan community, is transformed from a mountaintop village into the enchanted forest of Robin Hood folklore. The clouds descend over the ridge like a scrim and the feeling -- the inability to see anything -- can be claustrophobic, can make you blink and squint and hyperventilate in the thick, wet air. Anything might suddenly appear -- cars, monks, cows -- where once was only thick gray fog. Unable to see more than 10 feet down the steep, winding path, you can almost imagine a band of merry horsemen emerging from the pine trees lining the road.

Our guidebook told us the 14th Dalai Lama had a presence so large he filled up the room during his public audiences in Dharamsala. Now suddenly we -- a traveling American writer and photographer -- had been granted a private audience with him. Would his presence, I wondered, overwhelm me? Would I be rendered inarticulate? Would I feel a transcendence afforded legends standing in the presence of this reincarnated demigod? It occurred to me that the cleanest clothing I had was an orange T-shirt that said "Life is Good" -- which seemed mildly inappropriate when meeting a man in exile.

Before leaving Chicago a month earlier, I had not been granted an interview with the Dalai Lama. In fact, I had been told by his private secretary that he would be in Portugal when I was due in Dharamsala. But my photographer, Ann Maxwell, and I had been delayed in Tibet by mudslides and closed roads and we had arrived in India days later than anticipated. Infuriating at the time, this now seemed like a wondrous stroke of dumb luck.

We were on a two-month exploration of all things Tibetan. Our itinerary included Nepal, the first stop for all incoming Tibetan refugees, Tibet, Dharamsala and London, where the Tibet Information Network is based. We investigated increased violence inside Tibet, forced sterilization of Tibetan women, refugees, feminist nuns and dissident groups like the Tibetan Youth Congress. Meeting the Dalai Lama, of course, had always been our greatest hope for the trip, our apogee.

The night before our interview, our nerves nearly combusted. Ann checked her film, flash, batteries and lenses half a dozen times. I checked my tape recorder, pens, batteries and questions; I read more than half the Dalai Lama's autobiography in one sitting; my Chicago Tribune editors called at midnight and went through my questions twice.

Ann believed we would feel it, feel that something that was missing from the presence of ordinary mortals. I was more skeptical. Perhaps he had grown into his power and title not because he was exceptional, but because he had been groomed from age 2 to believe in his own preordained position, in the same way that geishas, slaves and royalty evolve into the roles they're told they command. Perhaps any man would have a presence as large under the same conditions.

And yet, in "Civilization and Its Discontents," Freud begins by discussing the attraction that all people have for power -- in themselves or in others. But the greatness of those we admire, he says, rests on "attributes and achievements which are completely foreign to the aims and ideals of the multitude." Certainly 50 years of peaceful perseverance in his campaign for Tibetan autonomy put the Dalai Lama in this category.

In Lhasa, the capital of Tibet, we had spent a great deal of time at the Potala Palace, the Dalai Lama's former 1,000-room winter home, from which he had fled the Chinese in 1959 disguised as an armed guard. Both the Potala, where 10,000 monks once lived, and the Norbulingka, his summer palace, have been left exactly as they were when he fled them -- a Phillips radiogram in the bedroom, two 1927 Austins and a 1931 Dodge parked behind the palace. The Potala now has just a handful of monks who attempt its upkeep and wait for the Dalai Lama's return. Though the Chinese advertise that it's open for tourism only several days a week, I went often, again and again, through its dark labyrinth of hollow rooms where plain-clothed monks sit quietly and refill yak-butter candles in silver chalices; they smile at the tourists studying the deity reproductions, the faded blue, red, green and yellow silk cloths that hang from the ceiling, the white scarves draping over Buddhas. Here flickering candles shoot wavering shadows on the dark red walls and the quiet is the kind reserved for places where tragedies too big and too close to accept reside: Dachau, the killing fields, Rwanda, My Lai.

In broken English, translators attempt to explain the Tibetan Buddhist sects -- the yellow-head sect or the red-head sect; they point out the Green Tara, or the Buddhas of compassion, wisdom, patience. If asked, they will say the Chinese have offered them opportunities that they never got under the Tibetan government -- though these 20-year-old translators, who smile at the naiveti of Westerners believing Tibet should be free of China, are themselves rarely old enough to remember when their country was ruled by its own people. And in each room of the Potala, far up in a dark corner, drilled into the 300-year-old wood and charting each movement of the monks, each conversation, each wistful gaze they offer, sits a bolted white camera.

I closed my eyes in one room, breathed in the thick scent of yak butter and tried to imagine the voices of 10,000 monks, the chant of the Dalai Lama in his home, his footsteps on the stone ground, the flowing silk robes he once wore when both freedom and country belonged to him. The Potala was like an ancient building undeserving of the historical status afforded it because its history was still alive and well on a misty mountaintop. I opened my eyes and for a long moment, stared into the dark lens of one camera.

The Dalai Lama's home in Dharamsala is much less

grand. Armed Indian guards stand behind an iron gate

leading to his residence and offices; two metal

detectors are positioned in front of and next to the

gate. Among pine trees, several one- and two-story

buildings dot the land beyond the fence, but the fog

was so heavy I could never see more than a few feet

past the gate.

Before meeting the Dalai Lama, journalists are

required to give their questions to the private

secretaries, partly for security and partly because

his holiness has a reputation for long-windedness;

knowing this, the secretaries often help to rephrase

questions in order to fully utilize the time allotted

in an interview -- in my case, 20 minutes. As I sat there

going over my questions about India's nuclear testing,

Tibetan autonomy and Clinton's last visit to China in

June of 1998, I felt as if I'd entered a parallel

universe, a place where this interview should not have

been happening. What would we have discussed, I

wondered, if it was happening at the Potala.

The Chinese have allowed portions of Lhasa -- encouraged

it even -- to become a shrine of all things Dalai Lama,

all things Buddhist, as long as references encapsulate

only the first through the 13th Dalai Lamas and

as long as the numbers of monks and nuns remain far

below the pre-1950s population. Praise could be

bestowed upon the fifth for expanding the Potala to

its present glory, but the 14th Dalai Lama,

the current exiled leader and winner of the Nobel

Peace Prize, was relegated to the memories of his

followers and his enemies, neither of whom spoke of

him publicly. Denouncing a fact, though, hardly makes

it less true.

As I wandered the narrow, cobbled streets of the

Tibetan side of Lhasa, I thought often about the Dalai

Lama. I didn't know then, of course, that I would meet

him, but I felt a sort of shame in knowing that,

unlike him, unlike the refugees who had fled, unlike

his countrymen who had been jailed, persecuted and

killed under Chinese rule, I was free to enter and

leave the country almost at will. Even though the

Dalai Lama, when he lived there, never roamed the

streets like an ordinary citizen but was in public

rarely and only with an entourage, the streets still

felt as if they belonged to him. I met many who

carried thumb-sized photos of him in the folds of

their robes and I wondered what it was like inside the

Dalai Lama's memory. Surely the city, even without the

obvious Chinese influence, had changed. When he longed

for Tibet, I wondered, what was the Tibet he was

longing for?

Before our interview, Ann and I bought white scarves

to offer him and we learned how to prostrate and hoped

he would recognize our cultural sensitivity. I was, of

course, in internal pandemonium, my stomach ached, my

hands shook, but I also knew there was safety in this

interview. Above all else, he was nice. I'd read his

book, I'd visited his country, my editors believed in

me, I knew to look him in the eye, and most

importantly, Ann believed I could do it, which was

worth more than everything else combined.

When the time finally came, we, with our equipment

and our white scarves, were led to a sidewalk where the

Dalai Lama, flanked by two men, waited for us. He wore

his standard maroon robe with a gold tank top

underneath and stood, arms at his side, stoically,

watching my approach. He was taller than I had

guessed. I wondered if the walk toward him was

included in my 20 minutes. It was, in memory, both

the longest and shortest walk of my life, akin to what

a bride must feel when the aisle stretches out before

her, yet suddenly there she is, in front of the

minister. I offered a half-grin -- I am a habitual

smiler. He didn't flinch. Before I could speak, he

snatched our scarves and tossed them to his secretary,

grabbed my hand firmly and pulled me into his

reception room. "Not much time," he said gruffly.

I nodded vigorously. His voice was deep and loud, not

at all the gentle monk I'd envisioned and my hand was

red where he'd grabbed it. I took a deep breath and

launched into a question about India's nuclear

testing. The phrasing was important. He did not

support nuclear weapons, war, or military action in

general; he wanted a demilitarized world. What he

supported was the right to such testing if, and only

if, world powers like the U.S. also engaged in such

"rights." By most accounts, he was misquoted. As he

answered the question, I began to wonder if he missed

Lhasa's thin air, if the Dharamsala dampness bothered

him, if he envisioned the sparkling minerals that

glinted like jewels off mountains in the sun all along

the Tibetan plateau. I wished I'd brought him

something from Tibet -- some yak butter or prayer flags,

a story of hope. Did he miss the Kham warriors who

wove turquoise into their long hair and the days when

the words foreign policy, United Nations and refugee

meant nothing to him? Today, would he get in that '27

Austin and plow through the winding alleyways near

Lhasa's Jokhang Temple? Did he envision himself

wandering the hallways of the Potala? Would he

recognize its hollow silence?

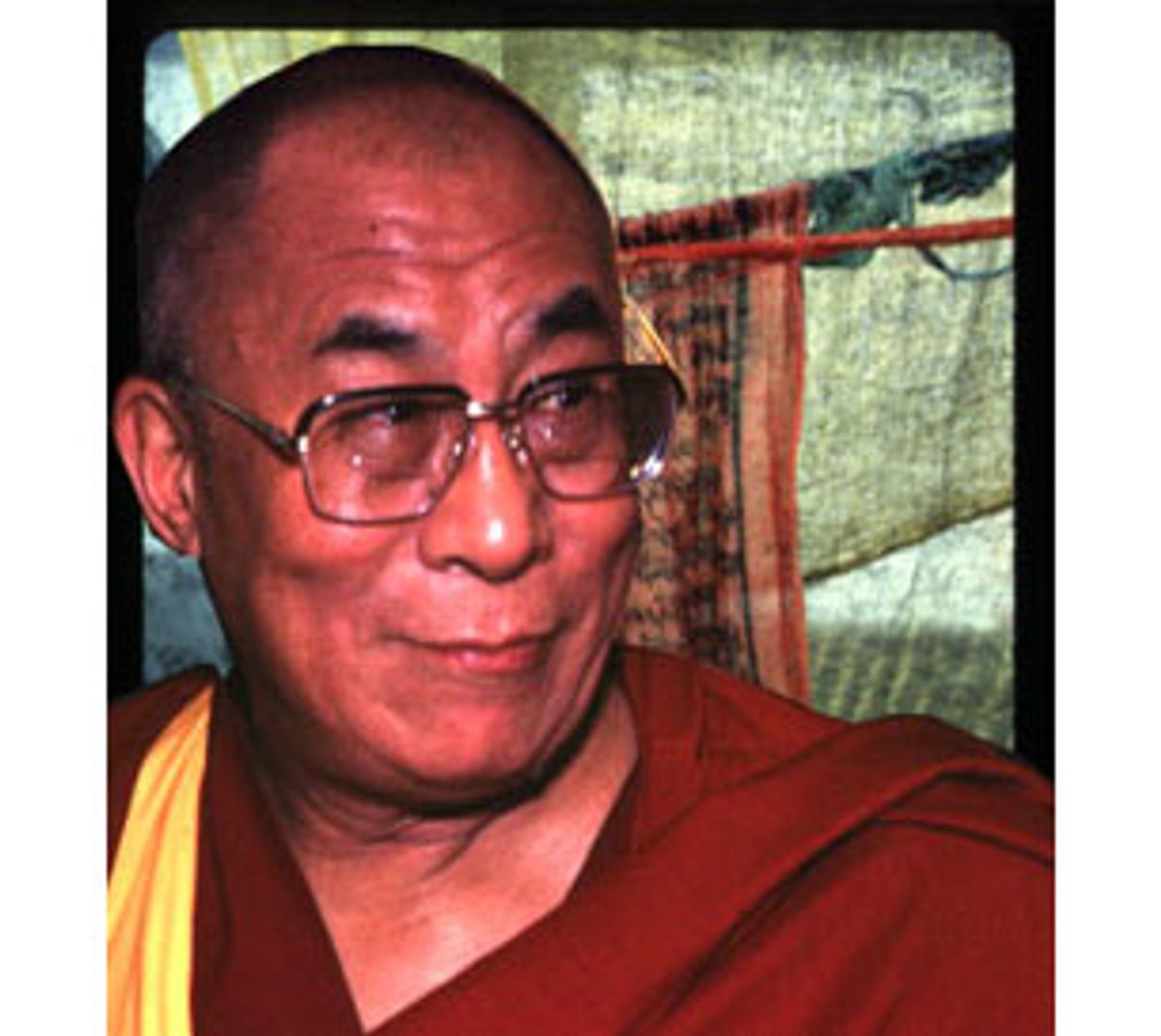

He was a stocky man with gray stubble on his head, a

long face, and large, metal framed glasses. His

answers were complex and his English halting. Every

few moments he looked to his two secretaries who sat

in the room with us and asked them to clarify words in

Tibetan, which they would then translate into English

for me.

The day I interviewed the Dalai Lama happened to be the day after President Clinton admitted to having an improper relationship with Monica Lewinsky. This was before the U.S. had split down the middle, before the partisanship, the hatred, the petty slandering and questioning and distrust. We knew only that the news had reached even the mountaintop in Dharamsala and that we felt betrayed and disappointed and hurt by our president. In my second question, I'd begun with Clinton, intending to ask about his visit to China. Before I could finish, the Dalai Lama drew his head back in surprise and looked at me incredulously. "You mean with Lewinsky?" he shouted.

I froze. Behind me, Ann's camera shutter stopped. I bumbled an apology on behalf of my president. But suddenly I realized the irony of discussing the world's biggest sexual faux pas with the world's most famous celibate man and I burst out laughing. That the Dalai Lama, Bill Clinton and Monica Lewinsky had entered my mind's trajectory simultaneously seemed sacrilegious even for a democratic agnostic. I realized that I hadn't broached this issue with his secretaries, but I pressed ahead anyway. "Actually," I laughed, "that's not my question, but I would like to know what you think."

He threw his head back and laughed with me. All at once, the tension dissolved, he slapped his hand on his knee and together we cracked up. Even his secretaries, who were largely humorless, laughed; Ann snapped photos and suddenly I saw that the way to the Dalai Lama was through his laughter. Here was a man who had escaped his country, who had endured for nearly 50 years without wavering, indeed who never even called his enemies such and he had a laugh as big as the sky. I've heard that he knows the power of his own laugh, that he has used it to manipulate other journalists, but with me it felt wholly sincere. I couldn't help thinking of my country, of the ultimatums we offer to the Iraqs and the Bosnias and the Vietnams of the world, of the shame we all feel, Democrat or Republican, at having officials who lie and get caught. But if a man like the Dalai Lama, who had lost an entire country and countless friends, could still lose himself in gales of giggles, surely there was hope for the rest of us.

We discussed politics, religion, autonomy, refugees, opposition groups and Chinese oppression, but the thing I remember most was his penchant for laughter. "You know," he spoke in a conspiratorial whisper about midway through the interview, "you really are spoiled. Your generation."

I told him my grandmother had said likewise for 30 years.

"I think the younger generation of America all have great potential if utilized properly," he said. "They can think, and that's important."

My 20 minutes turned into a half hour and my half hour turned into an hour and we laughed and talked and joked. He grinned at Ann's camera. He asked if we had enjoyed India. He put his hand over mine when we talked of refugees. When it was all over, I asked him how he had endured for 50 years -- with that deep well of laughter -- and he told me this story: "One Tibetan monk who is now close with me came [to Dharamsala] in the early '80s [and] joined with me. He [had] spent more than 18 years in a Chinese prison labor camp. So we used to talk and he told me on a few occasions he really faced some danger. So I ask him, 'What danger? What kind of danger?' -- thinking he would tell me of Chinese torture and prison.

"He replied, 'Many times I was in danger of losing compassion for the Chinese.'"

Ann and I gasped. He paused and studied us.

"That's marvelous, isn't it?" he grinned.

Save for that story, most of his answers to my questions have faded from memory. But I will never forget the sound of his big, booming laugh. I don't know if the Dalai Lama fills a room because of who he is or because of what we've made him, but I think now that it doesn't matter. I think what people really mean when they say he fills a room is that he fills their hearts.

When the interview was over, he motioned to one of his secretaries who then disappeared into a back room. Reappearing moments later, the secretary handed each of us a tiny white envelope. Inside, was a silver Tibetan coin -- the kind not used since the Chinese takeover -- made sometime between 1906 and 1912. On one side was inscribed "Gaden Phodrang," which refers to the Tibetan government; on the other was a lotus circle, which, in Tibet, represents victory in all directions. The Dalai Lama wanted us to have them. The secretary later told me that he gave them out only to those he felt an affinity toward, those "new friends and old," in his words, who "constantly refresh me." The secretary also handed him the two white scarves we'd brought with us. Placing one around my neck, the Dalai Lama peered closely at my shirt. "'Life is good,'" he read aloud. "That's good, yes." Then, taking my hand in his, he squeezed it and leaned in toward me. "Now tell me," he whispered, "about Tibet."

Shares