The 44 remaining inhabitants of Pitcairn Island -- the tiny British colonial possession in the South Pacific, inhabited for the last two centuries by the descendants of the mutineers from the notorious HMS Bounty -- are currently facing a crucial choice: Pay the full market price for the curious luxury of living lives of magnificent isolation or abandon their rocky mid-ocean home forever.

The British government, which has subsidized the minuscule possession almost as long as it's been a colonial outpost, has in recent weeks made it clear to the islanders that it is no longer prepared to do so. At the beginning of this year, the authorities freed the basic necessities of island life -- electricity and freight, mainly -- from the price controls that made them affordable to an island people who have for years lived no more than a frugal subsistence.

But at the same time, Britain has also held out the vague promise that later this year it might begin work on building a tiny airstrip on the mid-oceanic outcrop. This would allow people who want to remain -- and who will pay for the privilege -- to have at least rudimentary contact with the outside world.

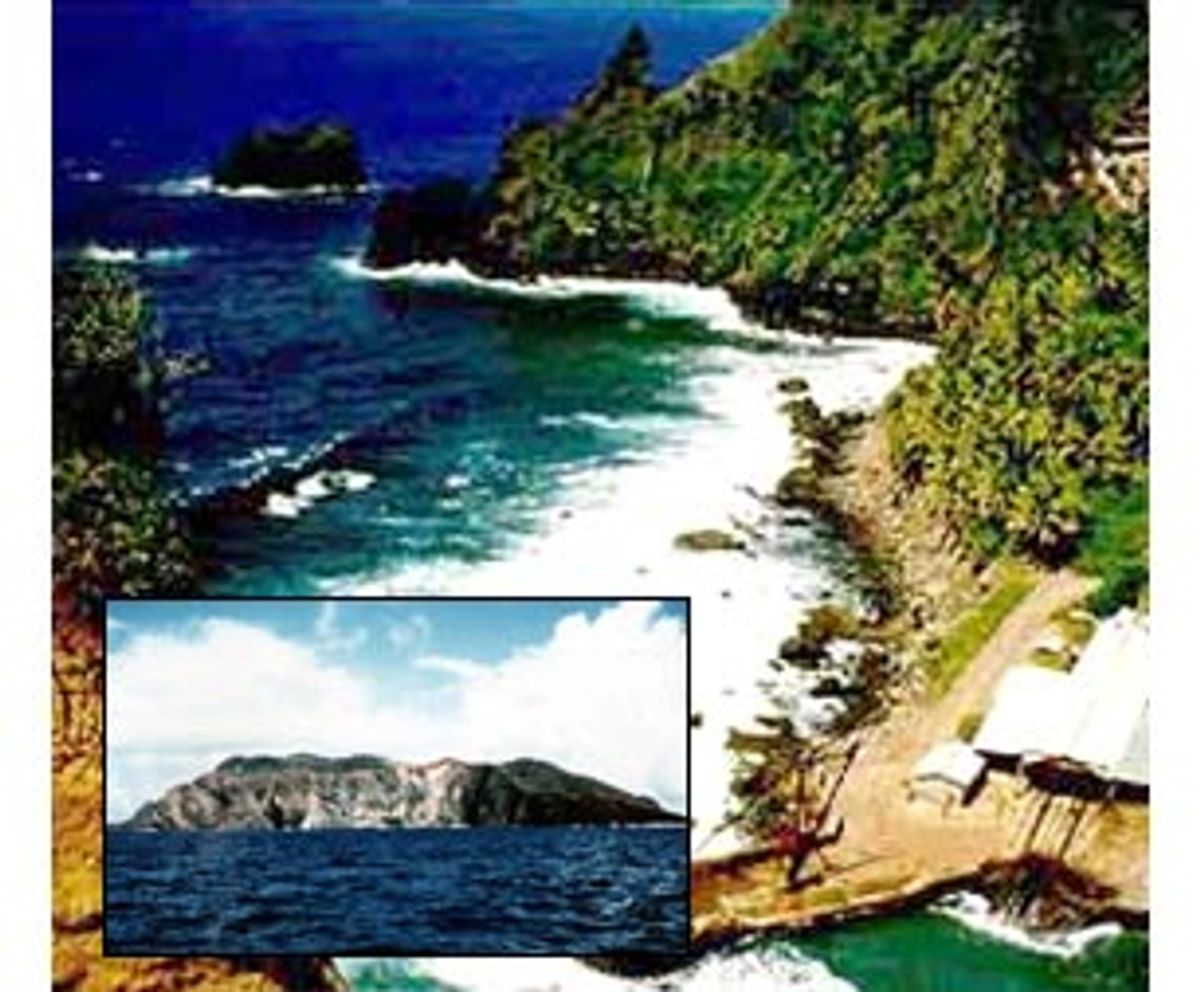

Currently it is only the occasional passing passenger liner and a thrice-annual cargo ship that deliver goods to the island. More often the passing ships that stop do so to take Pitcairners away. The ships take them to New Zealand and Australia for education, employment or, as emigrants, the chance of a better life. The population, which 50 years ago stood at more than 200, is now down to the smallest number that can properly be called a community. The remaining 44, defiant in their pride as British citizens and determined -- at least until very recently -- to cling to their precarious existence, have become one of the world's more charming curiosities. They are the stuff of Trivial Pursuit questions and gawking from the few tourists who are rich or adventurous enough to make it here.

Pitcairn, first seen by Europeans in 1767, was settled in 1790 after the infamous mutiny against Capt. William Bligh -- well known to fans of Charles Laughton and Marlon Brando, who starred in the two epic movies based on the story. Fletcher Christian, his eight fellow mutineers, six Tahitian men, 12 women and one child landed at Pitcairn in what is now Bounty Bay, burned the British man o' war to the waterline and settled. They remained undiscovered for 17 years: Smoke from their cooking fires was eventually spotted by an American whaling vessel, whose skipper on his return home broadcast the news of the settlement to an incredulous and fascinated outside world.

The romance of the Pitcairners' early story has never quite been matched by the realities of the islanders' insufferably dreary lives. The island itself is hopelessly cut off from outside contact -- it is 300 miles from the nearest inhabited atoll, it is well off the normal trans-Pacific shipping lanes, its coast is too rocky to allow many landings from most vessels able to heave-to offshore and its topography is too mountainous to allow enough agriculture for more than a few score inhabitants to live on. A century ago, with famine and privation depleting the colony's numbers drastically, the entire population decamped to the former prison colony of Norfolk Island, midway between Australia and New Zealand. Today many of the lineal descendants of Fletcher Christian and his men continue to live there, comfortably and in some prosperity.

But at the turn of the century a determined minority of Pitcairners decided to return to their tiny island, and -- with British colonial assistance -- to try to eke out an existence. It is these people -- most bearing the historic Bounty surnames of Christian, Young, Warren or Adams -- who are at the center of today's agonized discussions: Should they be encouraged to stay put on the island, and should the extraordinarily high cost of keeping them there be paid for by the British government? Or should the colony be closed down for good, and the people moved back to Norfolk, or elsewhere, with the tacit acceptance that some colonial anachronisms are simply too much of a luxury to afford?

Keeping Pitcairn going costs someone, somewhere, a great deal of money. Electricity costs about U.S. $1 per unit to generate. Each time a cargo ship stops, the island has to pay $3,000. Cargo costs several thousand dollars per ton to transport. A qualified nurse must be supplied to deal with medical problems that arise -- and a real emergency, involving ships or perhaps helicopters, can mean unimaginable expenditure.

One young islander has to be trained (by an officer temporarily posted from London) to perform police, customs and immigration duties. A teacher has to offer the compulsory education to the half-dozen island youngsters. And once each child has reached high school age, he or she has to be shipped to New Zealand, taught and given board and lodging -- all at the expense of the someone, somewhere, who pays the Pitcairn-bound taxes. And that, most certainly, is not the Pitcairn islanders, for the simple reason that they do not earn any appreciable money on which any taxes could be levied.

No one on the island works -- beyond a half-dozen able-bodied men who occasionally repair the rutted mud roads or drive one of the community's aluminum longboats out to greet passing ships. The only official island revenue comes from the sale of postage stamps; the only income for the islanders comes from the sale of carved Bounty models, sharks and T-shirts to sympathetic tourists. The former sum is barely sufficient to pay for the official running of the island; the latter allows the islanders to buy basic goods, beyond what they grow and farm.

Twice in recent years, schemes that might have proved their salvation have failed. The first came 10 years ago when an eccentric coal-mining millionaire named Smiley Ratliffe, from Frog Level, Va., offered to buy Henderson Island -- part of the four-island colony, about 60 miles from Pitcairn -- so that he could start a community of like-minded Virginians. For a 99-year lease, he offered the British government $5 million, a small airstrip on Henderson and a ferry that would allow Pitcairners easy access. For the first time, in other words, the islanders would have real contact with the outside world.

But the World Wildlife Fund objected, claiming that Henderson Island sported a flightless rail, a fruit-eating pigeon and a uniquely rare species of snail. The British agreed and turned down Ratliffe's offer. To this day, the islanders smart at the memory: "So close to some kind of prosperity," snorted Mavis Warren in an interview, "and then it all failed because of one wretched snail. What do we care about a snail, for heaven's sake?"

The other scheme, which is still being pursued, is the drying of island-harvested fruit -- mainly pineapple -- and the marketing of it in New Zealand. The much-vaunted Bounty brand of Pitcairn fruit, which was supposedly grown in "the world's cleanest air," soon fell victim to rumors of contamination from the French nuclear testing site at Mururoa Atoll, 500 miles west, and well out of the track of the prevailing southeasterly trade winds. If that were not enough, the British government's sudden removal of the island's generous electricity subsidy now seems likely to doom the project altogether.

Tom Christian, the great-great-great-grandson of Fletcher Christian, and one of the most publicly determined to keep the tiny community together, said that by raising the electricity costs 150 percent, as has just been announced, "our one chance of making a go of things seems to have been condemned."

"Now what is going to happen to us?" he asks. "If we cannot pay our way, if we cannot survive without help, and that help is taken away -- what will happen to the community?"

The question is all the more pertinent now, considering the current discussions about building a 2,000-foot gravel airstrip on the eastern side of the island -- a project that would be underwritten almost wholly by the British government. Soldiers, like the British Royal Engineers who built the island jetty 15 years ago, will probably construct the airfield as part of a training exercise. If built, it could provide a link with the outside for those willing to pay for the privilege of remaining on Pitcairn. There could be regular connections with Mangareva, 300 miles away in the French possession of the Gambier Group.

And it is this French connection that seems to offer -- heresy though this will sound to most British imperialists -- the best long-term solution for Pitcairn's current dilemma. For if the airport were built, if connections to the Gambiers were established and if Pitcairn and its three sister islands were then to be handed over, sold or leased to the French colonial authorities, then some logic and perhaps cost-effectiveness would settle on this remote corner of the South Pacific. The French have vast territories in the region: For Paris to add four more tiny islands and a few thousand more square miles of sea to their possessions would be a trivial new responsibility.

The Pitcairn islanders, who have seen all too often in recent years the appearance of French warships and aircraft in their territorial water and airspace, have long been hostile to the idea of a French-run Pitcairn. But now that the choice is being offered to them so very bluntly -- pay up or prepare to leave -- the French choice may turn out to be the only one that makes sense and will permit this curious relic of mid-ocean history to survive at all.

Shares