Six-year-old Dustin stares out from the computer screen and offers

a "say cheese" smile. Dustin, a caption tells us, enjoys "playing soccer, riding bikes and watching cartoons." He's also been known to "hit, bite, kick and grab," but with "appropriate services" is expected to outgrow these behaviors. Dustin is looking for a family. Specifically, he is looking for a "two-parent home and would do best in a home with no other children."

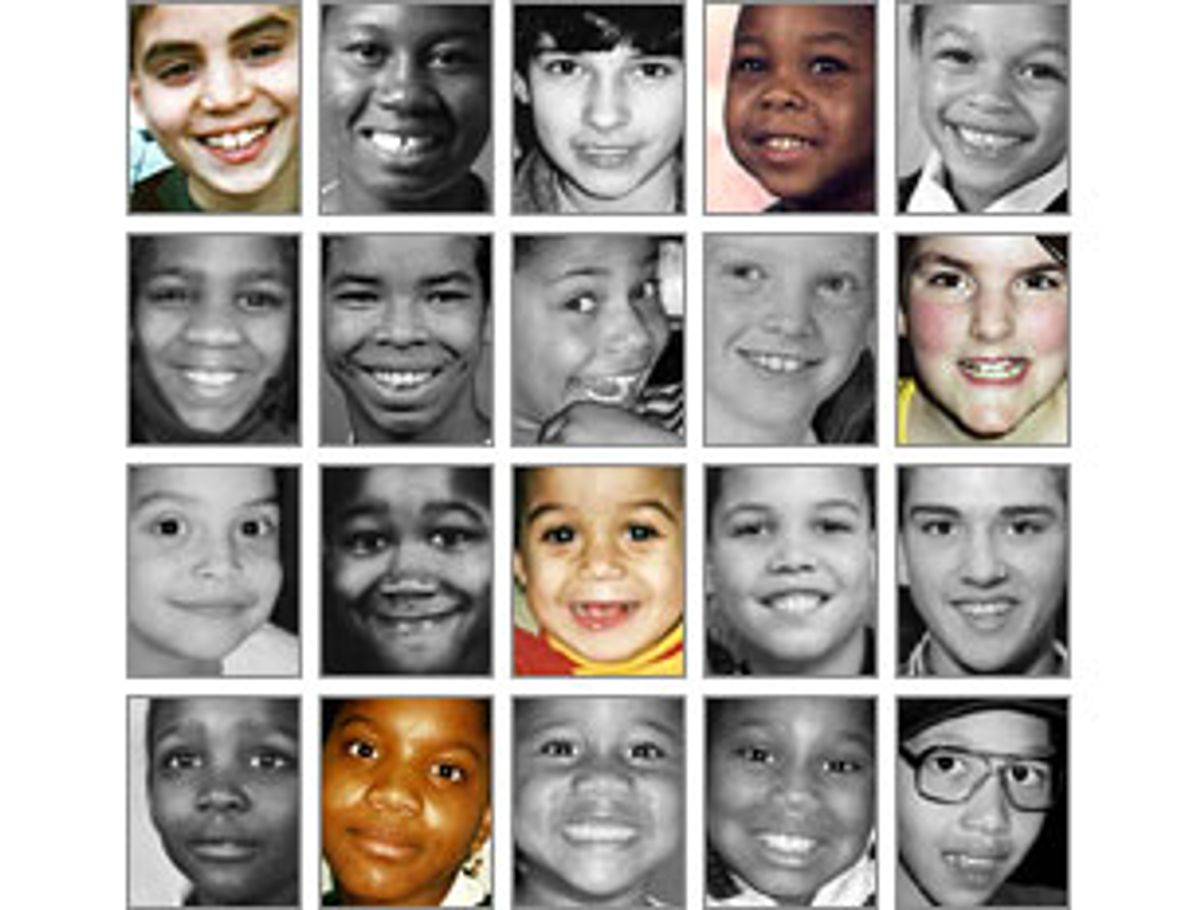

The little boy's bio reads like a personals ad but functions more like the prelude to an arranged marriage, since Dustin himself was not involved in its composition. Dustin is one of 1,400 foster children currently listed online in FACES of Adoption, a database maintained by the National Adoption Center (NAC) in Philadelphia and Children Awaiting Parents in Rochester, N.Y. Thirty-seven states run their own "photolisting" sites as well, and the federal government will soon be taking bids for a comprehensive national site. The Clinton administration

has pledged to double the number of adoptions out of foster care by 2002 and

has proclaimed the Internet central to its strategy.

Exploring the FACES database is an unsettling experience, one that

forces even a casual visitor to examine, however briefly, her own

prejudices and capacities. The search engine allows you to enter criteria

such as race, gender and age, and to indicate, on various numeric

scales, the level of physical, mental and emotional disability you feel you

can accommodate. A search for the most desirable adoptees -- healthy white children, or infants of any race -- will yield zero to very few. As you move up the disability scales,

photographs of children begin to download by the dozens or hundreds.

The descriptions of each child -- submitted by social workers across the nation, who generally list only those "hard-to-place" children for whom they have been unable to find local homes -- are hyperlinked to definitions of their various deficits and disorders. Once prospective parents e-mail their

interest in a particular child, the NAC staff puts them in touch with local

social services departments, which take the process from there. The NAC

has facilitated 114 adoptions, most

of them interstate, since it launched the Web site in 1995. The first, and farthest, was from Pennsylvania to

Alaska.

Susan Marshall came across the Web address in an adoption

magazine a few years ago. Now she's hooked. She uses the Internet

regularly -- she's studying for a master's degree in teaching through an

online program -- and checks in at FACES every time she logs on.

Susan, 38, and her husband, Jeffrey, 36, already have nine adopted children of

various ages, races and levels of disability. (Jeffrey also has one biological daughter.)

The Web wasn't around when the Marshalls started adopting children. It has, however, made it a little harder to stop. A bulletin board in the couple's bedroom is papered with ink-jet images from the FACES Web site: Duane, Tanesha, Molier, Christina, Tanka, Nykkole, Latisha, Octavia, Angelica. "If I had my way," says Susan, "I'd have every one off that Internet and adopted."

Turning onto the long dirt driveway that leads to the Marshalls' home in north central Pennsylvania, past the wooden sign in the shape of a pig that bears the names of each of their children, it's tempting to imagine a scenario out of "60 Minutes": A saintly country couple tending to their personal rainbow of damaged and abandoned children. But the Marshalls, who built this two-story modular house on family land after their trailer home was destroyed in a fire last year, aren't like that.

Jeffrey, a school custodian, is no Cliff Huxtable and doesn't aspire to be. When an older boy threatened to jump out the window a few years back, Jeffrey says

he dared him, "Go ahead." ("You forgot to mention the window of the double-wide was 3 feet off the ground," chides Susan.) The Marshalls both have Native American ancestry -- Iroquois on Jeffrey's side and Sioux on Susan's -- and like to think that their home replicates the gathering of tribes out of which the Sioux Nation was formed. When a neighbor called his wife a "nigger lover," Jeffrey came across him later in town and slammed the man's arm in the door of his truck. (That part was an accident, Susan interjects.) Jeffrey says he relates to his children not because he's so good but because he grew up bad -- poaching, brawling and some other things he won't specify because he never got caught for them -- and he knows what it's like to be an angry kid.

This is how their son James -- a sandy-haired, serious boy of 15 with

an extravagant spray of freckles -- describes what it means to be a Marshall:

"There's nothing better than having a set of parents that really love you

and want to take care of you the rest of your life. Like, if something is

wrong with your car and you need help, you can call your dad. But if

you're out there by yourself, who are you gonna call?"

Before coming to the Marshalls' home, James and his older brother, Vic, spent their toddler years moving from one foster home to another. It

was confusing, James recalls -- he'd get up in the middle of the night and

head for what he thought was the bathroom, only to find himself staring

into a closet. His memories of those early homes are mainly of emptiness.

"One time my foster parents were watching 'Wheel of Fortune' and I lost my

tooth. They said, 'Go throw it in the garbage.' I said, 'What about the

tooth fairy?' They said, 'OK, put it underneath your pillow.' When I

woke up, there was a dollar under the pillow, but the tooth wasn't gone."

When James and Vic were adopted six years ago, the process was

typical of the time: They had spent several years in foster care and then,

when their biological parents' rights were eventually terminated, they were

adopted by their foster parents of four years, the Marshalls. Their newest

siblings, 9-year-old twins Kandice and Katrice, joined the family via the

more contemporary channel. The Marshalls located them online and decided

to adopt the New Jersey girls before they even met them -- a process Susan describes as much faster and easier than any of their previous adoptions. She used to have to travel two hours to look at photos of children in the caseworker's office, then drive home and describe them to Jeffrey. "Now I just hit print," she says.

The years between the adoptions have seen significant changes

in how the nature and purpose of foster care are perceived. Traditionally, a central goal of federal child-welfare policy was to reunite children with their birth families; foster care was seen primarily as a way to keep kids safe until

their parents were able to take care of them. In practice, however, this left many of the nation's 520,000 foster children in the system for years, moving from one inadequate placement to another in a phenomenon that came to be known

as "foster-care drift." As the number of children in the system has grown, the pendulum has swung back in the other direction.

Now states are aggressively pushing for more -- and earlier -- adoptions. Parents whom the state has deemed unfit to care for their children are being given less time to redeem themselves before their rights are permanently severed. In 1997, at the urging of President Clinton, Congress passed the Adoption and Safe Families Act (ASFA), which requires the states to initiate termination proceedings after a child has been in foster care for 15 out of 22 months, or after six months for children under 3 years of age. ASFA also includes incentive payments to states of $4,000 to $6,000 for every adoption over previous levels. Other recent federal legislation prohibits using race as a consideration in foster-care adoptions (while requiring "diligent efforts" to recruit families of color) and authorizes tax cuts and subsidies for families that adopt.

Figures released in the spring reveal a 40 percent increase in adoptions of foster children since 1995, to a total of 36,000 in 1998. While the increase appears dramatic, it may actually reflect speedier processing of the easiest adoptions -- healthy younger children and those whose foster parents or relatives already wanted to adopt them. For the remaining 110,000 kids whose "permanency plan" (a court-approved agenda formed by a social worker) calls for adoption, theory has yet to meet practice. For that to happen, thousands of American families will need to adopt the children who are traditionally the most difficult to place: the older kids, the non-white ones, the members of sibling groups who need to

be kept together and the kids with physical or psychological problems.

The demand for healthy white newborns is at an all-time high in

the United States. So is the demand for homes for children who don't meet those

criteria. Of the foster children available for adoption, more than

35 percent are teenagers and another 17 percent are between 9 and 12. Forty-eight percent are African-American, 33 percent are white and 11 percent are Hispanic. Two-thirds have been in care for two years or more, almost a third for more than five years. Finding permanent homes for these children and the new ones who pour into the system each year may prove significantly more difficult.

The Internet is one widely heralded solution. "Technology will be

an ever more important part of achieving our national goals as we approach

the new millennium," President Clinton stated in a 1998 memorandum promoting

Internet adoption. "To give [waiting] children the future they

deserve ... we must infuse the public child welfare system with the power of

technology."

The idea of online adoption has also fueled the faith of tireless adoption crusaders such as NAC director Carolyn Johnson. When Johnson adopted her three children as healthy babies in the 1960s and '70s, they were considered "hard-to-place" because one was African-American and two were biracial. Johnson, who is white, began exploring the barriers to foster-care adoption.

"I was outraged that there were these children who were waiting to be adopted and nobody was doing very much about it," she recalls. "The attitude was, 'We don't want to push these children on people.' I said, 'You can't push children on people. People adopt the children they want to adopt. But how about just

telling them?'" Johnson has been telling people for more than 25 years now, through a number of old-media means, including a weekly column in a black newspaper

in Philadelphia, a segment on a local television program, annual

appearances on the Maury Povich show and periodic features in Essence

magazine.

But the Internet, she believes, "will be the vehicle to accomplish the dream I've had since I started this -- for every person to know we have wonderful children in this country who need to be adopted. People are more aware of Chinese baby girls than they are of U.S. kids. I believe that if you let the American public know who these children are, they will come forward to adopt."

Despite such high hopes and the triumphant language issued from the executive branch, however, many of those involved with Internet adoption caution that new software does not a revolution make. "Some people think that because the kids are on the Internet, it changes the process," says Gloria Hochman,

communications director for the NAC -- "but there are no shortcuts, no magic, no packing the kid up and shipping him off." After locating a child online, prospective parents must go through the same steps they would have had they found the child via the local social services department, including a "home study" by a social worker and a series of visits with the child.

Still, the use of the Internet is very much in keeping with

the mandate for faster adoptions. The children listed on FACES are legally available for adoption -- which is to say, their parents' rights have been permanently terminated, a process that has become swifter and more frequent in the wake of ASFA, although three out of four children who leave foster care still do so by returning to their families. One rationale for the tighter time lines is that children who are freed for adoption when they are younger stand a much higher chance of finding adoptive families than those who have spent several years in a series of foster homes and are well past the "cute" stage by the time the state starts marketing them to prospective parents.

On the surface, there is an appealing simplicity to the new

time lines, one that is very much in keeping with the current obsession with

"personal accountability": Why should children "languish" in foster care

while their parents squander chance after chance to get their lives

together? In practice, however, the question of termination is

contentious, complicated and painful.

One 14-year-old girl in foster care described to me a recent visit from a new social worker that left her shaken and angry. This young woman had been in "kinship" care with her grandmother for several years while her mother went to parenting classes, looked for housing and struggled to meet the

requirements for reunification. Her mother, she said, had never mistreated

her; her father, who had abused both her and her mother, was no longer in

the house; and she was looking forward to being returned to the mother she

loved dearly. Instead, the social worker informed her that a new law had

been passed and her "permanency plan" had been switched from reunification

to adoption. If her grandmother was not willing to adopt her, they would

find a stranger who would.

Her story may be the exception, but it illustrates

the dangers of applying sweeping federal guidelines to the complicated sets

of circumstances and relationships that make up individual families. And the

new two-year limits on welfare benefits raise the prospect of more children entering foster care -- and potentially being adopted -- primarily because their families' extreme poverty manifests itself as "neglect." For some children, adoption may be the best option, for others it may not. But the states get their $4,000 to $6,000 either way. If the state successfully restores a child to his biological family -- which is certainly in the best interests of many of the children -- it gets nothing.

According to Madelyn Freundlich, executive director of the Evan B. Donaldson Adoption Institute in New York, "Some people have expressed concern as to whether incentives might create a situation in which adoption would be considered too readily." But, she adds, state laws "set forth strict procedural requirements for terminating parental rights and fairly high evidentiary standards for proving parents unfit, so I don't know that the incentives would be tied to prematurely terminating parental rights."

- - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - -

-

Erin Albright is a tiny woman with a long blond ponytail and big

blue eyes. She and her husband, Jim, live in Alexandria, Va., with their

two adopted children -- Manuel, 19, and Alberto, 18 -- and 6-year-old

Eduardo, whose adoption is pending.

Like the Marshalls, the Albrights have experienced adoption at both

ends of the political pendulum. Jim Albright, a 35-year-old environmental

consultant, has cystic fibrosis, a hereditary condition, so he and Erin,

38, an educator, decided to adopt in 1991. They went to an adoption event

held by the county, where would-be parents were divided by interest into

three groups: international adoption, foster-care adoption and adoption

of African-American children. Jim went to the foster-care group; Erin

headed for the African-American group. The first question the woman running

it asked her was whether her husband was black. When Erin said he was

white, she was told she wasn't eligible to adopt a black child, so she went

and joined Jim in the foster-care group. At the end of that session, Erin

asked what portion of children in foster care were adopted each year and was told it was about 4 percent. "That was when we said, 'Bag

this,'" Erin says. "We were doing our best trying to find kids, but we

thought sometime in our lifetime would be nice."

Jim Albright's father had been in the State Department, and Jim had

grown up in Mexico, so the Albrights decided to look there. They got in

touch with a local social services department in Mexico and adopted Manuel

and Alberto, then 13 and 11, from a Puebla orphanage in 1992. By 1998, when they started thinking about adopting another child, the climate had changed.

Jim, who says he is logged on most of the day at work, is on a cystic fibrosis mailing list. About a year ago, someone posted a note saying there was a Mexican-American child with cystic fibrosis in Texas who needed an adoptive home and included the URL for the FACES Web site. Jim printed Eduardo's profile and brought it home to Erin. Three and a half months and piles of paperwork later, Eduardo joined the Albright family.

Like the Marshalls, the Albrights were not inspired by the Internet to consider adopting, but it did make the process easier. And in Eduardo's case, the Internet appears to have proven an astute matchmaker: Halfway across the country, he found brothers who share his ethnicity and parents who understand his medical condition.

On a recent afternoon, I watched Eduardo, an energetic child with the

posture of a boxer and the musculature of a miniature man, climb a tree

under the close supervision of his older brothers. The child in cyberspace

is an unsettling facsimile -- a human life reduced to a smiling photo and a

few flat lines of text. But the boy in the tree is as real as the day, the

fact of his presence obliterating the existence of his online double.

If the pretty sight tempts a visitor to drift into sentimentality, however, Erin Albright is on hand to yank her back. She and her husband are

passionate proponents of "special needs" adoption, of the rewards that come

from making a lifelong commitment to a troubled child. But they won't let

you underestimate how difficult it can be. Manuel and Alberto were

orphaned as small children. Both had lived in the street, rooting through

garbage cans for food; Alberto, in particular, had been terribly abused. He

arrived filled with a rage that sometimes seemed bottomless.

"Why didn't you adopt me before?" Erin remembers Alberto screaming

at her on a family vacation during his first year with the Albrights.

"Where were you? Why didn't you protect me?"

According to the NAC's Gloria Hochman, about 15 percent of "special needs" adoptions "disrupt" and the child is returned to foster care. Sometimes, adoptive parents are not given complete information about the range of problems children may bring with them -- not because agencies intentionally withhold information but because they may not have complete or accurate records on children who have been passed from home to home and social worker to social worker. In other cases, parents may find that love is not the panacea they thought it would be for older and deeply wounded children.

"My experience is that people are willing to help kids up to a

certain limit," Erin Albright observes. "They'll say, 'This is the

reasonable amount a human being needs in order to be able to function in

the world.' Alberto took us far beyond that -- way past what we ever thought

would be our limit." Their adopted children made the Albrights face a

question few people ever do, Erin says: "What if you really have to live

everything you say you believe? What if you have to live that day in and

day out when it's really hard and it just keeps on being hard and you never

know if it's going to end?"

On the other hand, Erin avows, "Having your life be easy is highly

overrated. There is definitely something about the amount of difficulty

being matched by the amount of reward. I'm sure most mothers have never

had their kids say to them, 'If you weren't my mother, I'd be dead by now.'"

The Albright family has grappled with just about every issue that

has made the question of foster-care adoption contentious. Race. Older

children. Attachment issues. Ongoing connection to the birth family.

They have responded with a combination of thoughtfulness and action. When

Manuel and Alberto returned from a visit to another brother and sister in

Puebla, missing their siblings and feeling guilty for having more than they

did, the Albrights offered to adopt the pair's 14-year-old sister and to try to obtain a visa for their 25-year-old brother. The sister got married instead, but the family is still trying to help the brother.

I ask Alberto, a sturdy young man with a full head of hair and

dramatic eyebrows, what his first thoughts were when he met his

parents-to-be. "They're white!" he recalls observing with alarm. Other

children in the orphanage had told him stories about white Americans: They

were big, strange, rich, with funny eyes. But over time, the white

Americans became Alberto's parents. Now, when someone asks Alberto why his

parents are white, he replies, with some impatience, "Because they're

white."

Asking Alberto a question is like turning on a tap: He goes

straight from silence to a prolific stream of talk. "I really like

adoption," he begins, "because all my life has been horrible, really

hell. Since I was a baby, every morning I wish I had a mother just to say,

'Good morning.' And a father to take me to soccer games and to see things

together."

Alberto remembers his first meeting with the Albrights in Mexico.

"The people were hugging me. Very strange. And they were crying. I thought, 'Why you crying, man?' I was not that happy. OK, I need a mother, but I was not that used to people touching me 'cause a lot of people beat me up. So I was a little bit scared of people, scared of adults."

At the Albrights' home, Alberto recalls, he would get angry when Jim and Erin embraced, because he thought it meant they were excluding him. "I was the loneliest child who needs so much love," he says. "I was scared if I would do

something bad they would take me back to Mexico." Over and over, they reassured him that was never going to happen. Eventually, he came to believe them.

"Attachment disorder? What do you expect?" says Erin, dismissing the notion that some children may be so emotionally scarred that they will never connect to a new family. "The question is: Are you willing to stay with it, to rebuild that kid emotionally not just from zero but from way down deep in negative numbers?"

Is there a search engine powerful enough to locate thousands of families willing to take on that question? The Albrights aren't necessarily true believers in the technology that brought them their youngest son. "The typical adoptive parents want a little baby that looks just like them," observes Jim. "Meanwhile, there are plenty of kids out there of various ages, in various circumstances, available for adoption. Is better publicity going to change that? There are so many societal issues at stake, publicity is not the biggest obstacle."

But watching Eduardo set off with Alberto to buy a fish for his new aquarium, or Kandice twirl through the Marshall living room in a gauzy tutu alongside her new sister Kayla, it's difficult not to marvel at the hand that cyberspace had in bringing these children home. Many adoptive parents have a strong sense of fate -- that somehow, by means that remain mysterious, the right child was delivered to them. The potential of Internet adoption may lie somewhere between President Clinton's techno-optimism and Jim Albright's guarded view. But if, as Carolyn Johnson believes, the way to get the wheels of fate turning is "just telling people," the Internet may prove to be a promising means.

As the late-morning sun lights up the green hills that surround the

Marshall home, a black pot-bellied pig nudges a red ball around the living room floor while an elderly beagle rests his head against a large-screen Sony TV that is permanently tuned to Nickelodeon. Energy seems to wash through the house in tidal cycles -- periods of television-watching and leafing through books alternate with bouts of spontaneous dancing. Children roll in and out of

Susan's capacious lap, nestle under her arm one and two at a time or

clamber over Jeffrey as he sits on the couch with an oversized mug of

coffee. When Susan gets up to do something in another room, two or three children trail behind.

The Marshalls' extended family -- grandparents, aunts and uncles,

cousins -- arrives for a "Rugrats"-themed birthday party for 4-year-old Ean.

As the children eat blue-frosted cake at low plastic tables set up in the

middle of the kitchen, the relatives comment quietly on the improvement

Katrice, who is autistic, has made in her table manners.

There are foster homes that look like this -- concerned parents,

bunches of kids, toys, games and birthday parties -- but they don't feel the

same. The difference here is that the kids all know they'll stay.

"Permanency" -- the stilted term that has become the buzzword for the

adoption crusade -- comes to life inside the Marshall home. Even when the

house itself burned down and the whole crew trooped across the field to

sleep at their grandmother's, these kids knew they had a home.

The younger children have no idea that their family exists at the

vortex of any number of bitter controversies -- over race, parental rights,

federal child-welfare policy. Because James is older and knows that

people tease children whose lives are in any way unusual, he has come to

understand that many things about his family are complicated. But Jeffrey

Marshall has passed on to his son the gift of a quick tongue, and James

uses it readily in defense of his family. In grade school, when his

classmates were harassing his brother, who has learning disabilities, James

walked to the front of the room and held up his hands. "I had my fingers

broken when I was a baby," he told the other children. "Did any of you

experience that? My brother's different. I'm different too."

Still, James also understands that some things are simple. "Being in foster care is like four people in a room, one in each corner," he explains. "Being adopted feels like all the people are in the middle, all talking to each other. It's not just you and the wall. Everyone's one."

Shares