Women I know, namely lesbians, are wont to inquire whether I'm a femme top or a

soft butch bottom. They ask if I have an inner gay man or an inner straight

woman. Do I like straight-acting, straight-appearing dykes, or do I prefer

more traditional-looking Sapphists?

Never having composed a personal ad, I retort, I possess answers to none of

these questions. "Well," these women ask, "what were you like as a little

girl?"

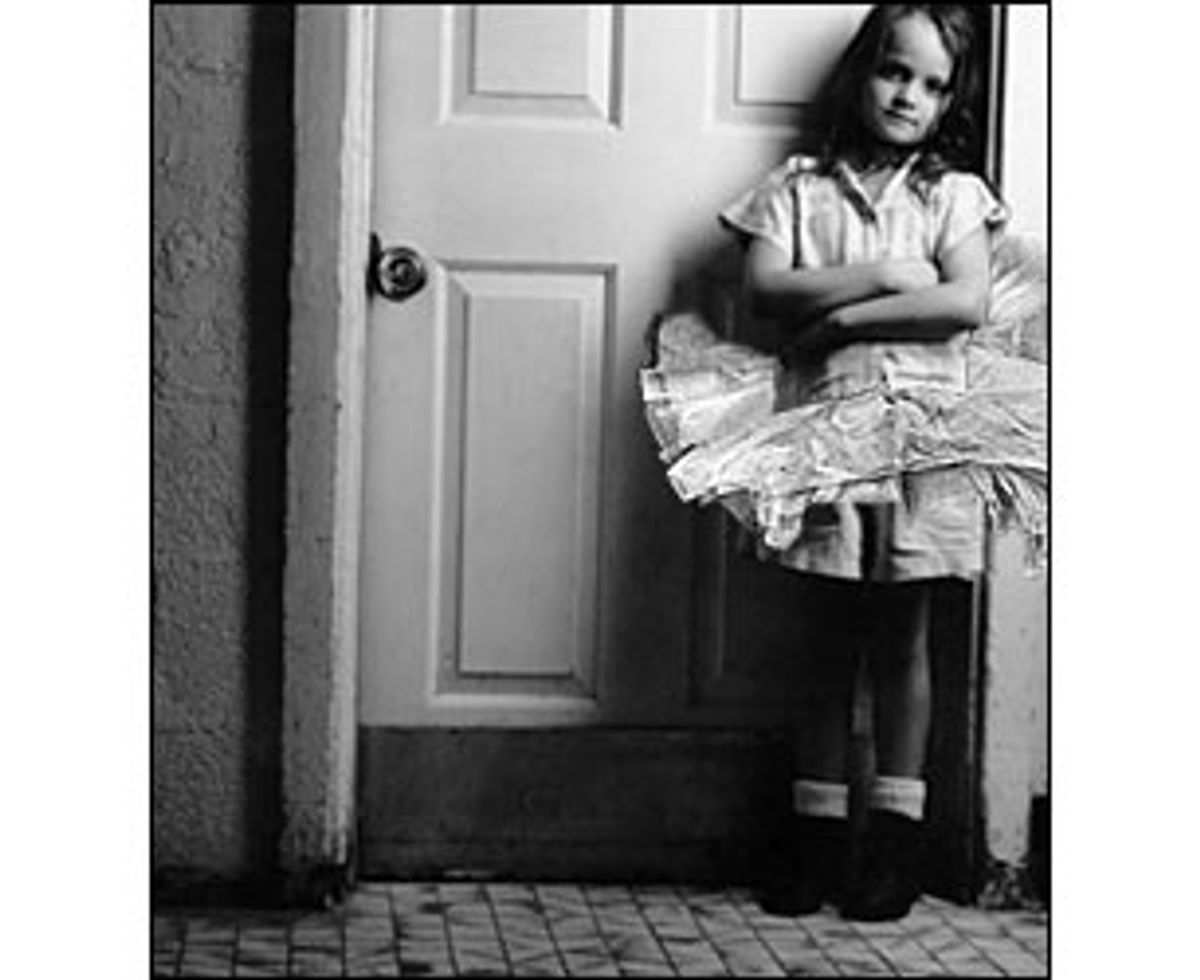

One thing I'm certain of: I was never a little girl.

It is not that I was robbed of a childhood. I was very much a kid, a small

one at that. But while other girls my age immersed themselves in play worlds

that included rainbows and unicorns, Barbie and baby dolls, kiddy kitchenware

and cosmetics, I was drawn to boy toys like "Star Wars" action figures,

Matchbox cars, Erector sets and the like. I coveted male privilege. From the

age of 4 until I was 10, I actually prayed to God, Santa Claus, "My

Favorite Martian," Samantha on "Bewitched" -- anyone who, in my mind, posessed

the power to grant me a wish -- for a penis. The boys I knew had license to be

kids, to play with games that were designed for children, not

adults-in-training. I wanted those games. I longed for those privileges. Give

me a dick, was my cry, or give me death.

I hated wearing dresses and refused to put barrettes in my short hair to

relieve my 'do of its androgyny. I was loath to get my nails painted

and would have given anything to trade in my Mary Janes for Chuck Taylors.

This fashion choice, though, was in no way indicative of any athletic

inclination I may have possessed.

As I grew older, my interest in all things "boy" refused to wane. I walked

with a swagger, insisted on wearing jeans, sneakers and T-shirts, and kept

male company. I prided myself on how often I was mistaken for a boy. Although

I was hesitant to do so, I actually had to insist to people that I was, in

fact, a girl -- even though that too felt like a lie. By the age of 11, my

bravado was starting to try my mother's patience. She felt that my

gait resembled that of a truck driver, and despite my compliance in getting

my ears pierced two years before, she wasn't appeased. She

decided to enroll me in a beginner-level ballet class at the Academy of

Movement, along with my hyper-feminine 8-year-old sister, Shana.

I'd seen the girls around school who went to the academy. They were in the

intermediate and advanced levels, had aspirations to a life of dance and

didn't strike me as particularly feminine. When they had ballet after school,

the girls would sweep their thin hair back into severe buns perched atop

their heads. Their bodies were wiry and lithe. Even the older, puberty-age

girls had flat, broad chests, shoulders held back like soldiers and

prominent, very strong thighs and calves. While they didn't exactly walk like truck

drivers, they did strut like ducks. I didn't understand how emulating these

aspiring ballerinas was going to make a girl out of me. These dancers looked

like eunuchs.

So I fought. I screamed. I even went so far as to cry like a girl. But there

was nothing I could do to get out of taking ballet. In addition to my

rigorous regimen of Hebrew School on Tuesday and Thursday evenings and Sunday

mornings, and my sixth-grade homework load, I had to sacrifice my Friday

evenings for what my mother referred to as a "lesson in grace." Not that I

had an active social life, but a kid likes to have choices, no? I had a very

bad feeling about ballet, but the check was already cashed by the Academy of

Movement, and money spoke volumes about commitment in our home.

The first Friday, we were informed that we had to purchase a uniform that

included pink Danskin leotards, pink opaque Danskin tights and pink Capezio

ballet slippers. Toward the end of our eight-week session, we would each be

presented with our very own complimentary pink tutu for a recital we'd

perform before the entire Academy.

I surveyed the room. It was filled with 15 7- and 8-year-old

girls gasping in delight at the prospect of pinkocity. I turned to my 8-year-old sister on my left. Her eyes were gleeful. To my right

sat a big girl who looked a few years older than me. I breathed a discreet

sigh of relief that I wasn't the oldest girl in class. But upon closer

inspection, I noticed that the girl's glasses were at least an inch thick, her dopey smile, unwavering. When she clapped her hands in joy at the

thought of a free tutu, I suspected that she might be retarded. When

she turned to me and cackled, my suspicion was confirmed: she had Down's

syndrome.

When our mother came to pick us up after our lesson, Shana ran to her,

excitedly reciting the shopping list of pink things. I remained silent.

"So, was it so bad, Kera?" goaded my mother.

"I'm not going back there. I am the oldest girl in the class, and I refuse to wear baby pink."

Then Shana piped up: "Georgie-Ann is 14!"

"See, Kera," retorted my mother, "You're not the oldest."

"Mom, Georgie-Ann has Down's syndrome."

"Oh." My mother was rendered speechless, if only for a moment. "Well, the

class has already been paid for, so you really don't have a choice. At least

you can learn something."

"Yeah, like you can't get your money back," I muttered.

My mother insisted I give it a chance. She was so invested in my pathway to

grace she actually tried to convince me that I might enjoy it. She knew nothing of the embarrassment I would endure, passing my middle school classmates in their

intermediate- and advanced-hued leotards, while I wore my beginner's pink. I would be voted the official butt of all school jokes. I dreaded my immediate future.

As an incentive, my mother offered to register me for softball in the spring

if I successfully completed the ballet course. I couldn't recall ever revealing

any interest in sports, so the incentive was lost on me. Would it be so bad

to return home after school, and just do my homework? Wasn't Hebrew School enough?

At first, I complied. I did the pliis and the demi-pliis, learned all of the

positions, performed them as well as anyone else in the class. But when I

caught a glimpse of myself in the full-length mirror, I was mortified. I

stood at least 5 inches taller than most of my classmates. I watched my Dorothy Hamill haircut as it bounced in the air. My

pink get-up, which gathered in rolls at the ankles and revealed the tangle

of my bunched-up cotton panties, was about as graceful as a body cast.

And if that feast for the eyes failed to satisfy my hunger for self-consciousness,

my gaze found its way to the small window in the door, where I discovered

three fellow sixth-graders peering into the classroom, fingers pointing at

me, hands covering giggling mouths. This class, and my presence in it, was so

"gay" -- in the sixth-grade, misappropriated sense of the word. How was I going to face seven more weeks? And how could I possibly show my face at school on Monday morning?

Each week that followed, I devised ways to get out of attending the next class.

My mother would not relent. Fine, I thought. I resolved to take the class

less seriously. No longer would I try to master beginning ballet. I would

resist. I would perform half-heartedly. I would become the class cynic, the

reluctant beginning ballerina.

This only served to get me paired up with Georgie-Ann. While she was trying

in earnest to perfect her movements, I was equally earnest in making mine as

clumsy as possible. Together, we became the anti-Fred and Ginger. I took her

stunted fingers in my sweaty hands and tried to spot her as best I could,

given my new cool and disinterested demeanor. She attempted to return the

favor, but more often than not, one if not both of us ended up on the floor.

I laughed at the spectacle of it all. My amusement was shared by no one -- not

by my seasoned and underpaid teacher, not by the kids in the class and

especially not by my younger sister, who looked at me in horror. Only

Georgie-Ann laughed along with me. And it was when she laughed that I

realized I might literally be dragging her down with me. I had no intention

of mocking her -- I was too self-absorbed to mock anyone but myself. I mean, I

had a job to do. I had to shame my mother enough to lose hope in me, and get

me out of beginning ballet before the recital.

It was not to be. The impending performance loomed larger with each passing Friday. The tutus arrived via UPS and were handed out two weeks before

the recital. Shana pranced around the kitchen in hers, with her hair wrapped

in Princess Leia-style danishes on either side of her head. I put

my tutu on for my parents, in an effort to prove how ridiculous my developing body looked swathed in infantile, pre-Lycra, limited-stretch nylon. My mom

stood her ground. She insisted that I looked just as she'd hoped.

When the night of the recital finally came, my instructor had enough sense to

put me in the back row of the stage. I mustered all of my courage to look

through, not at, the audience. Sitting behind my parents in the second row

were a middle-school classmate from the advanced level and several other girls

I sought to avoid. My eyes darted around the room, taking inventory of the

audience members who would witness my humiliation. My face alternated between

bright fuchsia and deathly white. And we had only just taken our places

on the makeshift stage.

I don't actually remember what happened during the performance. I can assume

that it passed without much ado; I was just relieved that it was over. I

sauntered over to my parents after the recital, only to learn that my mother

had enrolled Shana and me for another eight-week session, beginning in June,

after softball. Shana was promoted to the intermediate level. Georgie-Ann and

I would become reacquainted with beginning-level ballet.

In a rare instance of consistency, my mother remained true to her promise,

and decided that my dedication to ballet rendered me worthy enough to

register for the softball league. A small reprieve, or so I initially

thought. Here was an activity that required no grace whatsoever. I borrowed

my father's Wilson A-2000 mitt. I got to wear sneakers, a polyester mesh

baseball cap, a forest green T-shirt, jeans. There was only one problem: I was scared

of the ball. I would dodge when it was pitched to me, and run away from it

when it was flying toward my glove out in right field. My teammates hated me.

My coach tried to teach me to slide between second and third bases, but I was

too frightened to risk scraping my thighs. I ran in hesitant leaps, if I

remembered to run at all. I flinched at the plate when the ball was pitched

to me, even with my batter's helmet protecting me. If I could even achieve a

base hit, I was a guaranteed out. I was plagued with nightmares of

oversized softballs, wrapped in stiff baseball gloves, bludgeoning me to death.

Even as a faux boy, I was Queen of the Sissies. I spent a

lot of time on the bench, praying for rain.

Ballet proved that I had failed to become a girly girl, but that hadn't troubled

me because I knew as much going into it. But my stab at softball demonstrated

that I also fell way short of being an adequate tomboy. Where did that leave

me?

Perhaps this is not a unique quandary of pre-adolescence. But I must confess

that this legacy continues to plague me. While my adult body is undoubtedly

feminine, with curves and fullness, it belies my utter lack of grace and

athletic coordination.

In an effort to work with and not against my sex, I

wear my curly hair just above my shoulders, and my pouty lips are often

slathered in the fine Bobbi Brown products. I boast an

impressive clunky-shoe collection, and two pairs of heels. I wear lacy bras, and own an essential black dress. I even have a knack for accessorizing.

Yet when I put on a dress, I see myself as a football player in drag.

When I stand naked before the mirror, I half-expect to see a small-framed,

flat-chested, hipless androgyne. Instead, I am confronted with a strange

womanly body, one that apparently belongs to me.

I still walk with a slight swagger, but I can also be spotted wearing a Prada

knockoff purse. After years of studying gender theory and psychoanalysis

and undergoing psychotherapy, I remain at a loss about who or what I am, just as when I was 11.

For the sake of personal ads, bar inquisitors, matchmakers and any other

interested parties, I will venture to say that I am versatile. In bed, to borrow from the

gay lexicon, I am neither a top nor a bottom, but a "side." As an aesthetic, I alternately

confess to being femme with an inner soft butch, or perhaps a femme

top. I occasionally find that I possess an inner gay man, but am equally

inclined to relish my inner straight woman. Like many women, I strive to feel pretty, sexy, captivating and even ravishing, but I also want to feel strong, sexual and in control.

And when I was young, I just wanted to be a kid.

Shares