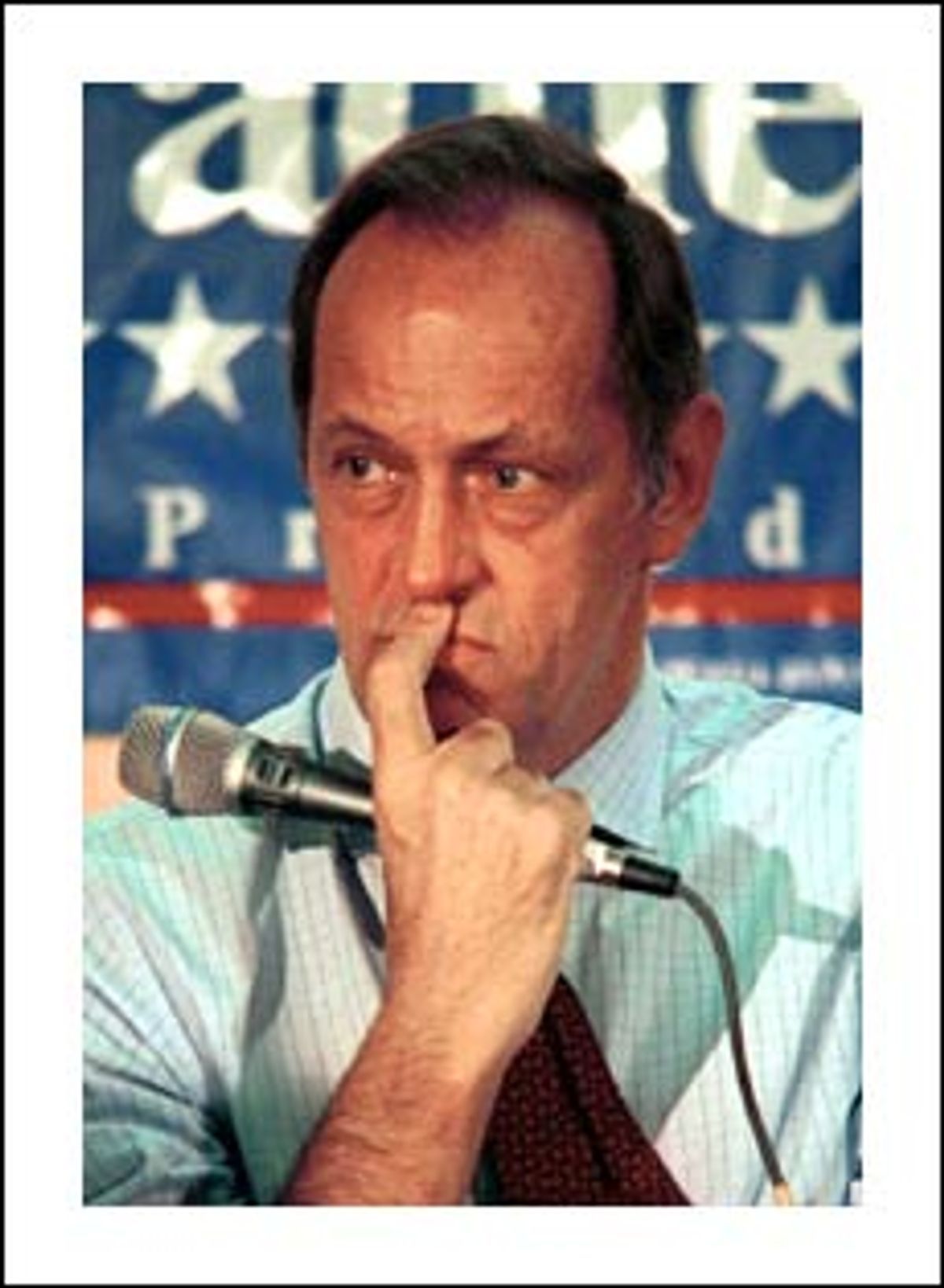

The last time I saw Bill Bradley, he wasn't looking terribly presidential. Speaking at a local community center here, clad in a rumpled red sweater-vest, Bradley gave a meandering presentation to a small group of latte-sipping San Franciscans. He took some questions, gave tangential answers, and raised some offbeat notions that got no coverage -- possible statehood for post-Castro Cuba, for instance.

There were no television cameras, just a couple of local newspaper reporters tucked away in the audience scribbling into notebooks. At a time when he was making a big deal of his concern about race relations, his staff had given reporters the wrong address for a local Juneteenth celebration Bradley was attending in the city's black community, which seemed a metaphor for his aimless campaign.

Much has changed in the last three months. Bradley's candidacy has caught fire at least with the media, thanks in equal parts to the struggles of front-runner Vice President Al Gore, Bradley's head-turning fund-raising success, and reporters' crowning boredom with a Democratic presidential primary that six months ago looked like it would be a coronation.

When Bradley came to Oakland on Thursday, for instance, to discuss his new $65 billion health care plan, a half dozen television cameras were there to watch, while another dozen kneeling photographers snapped away. On the same day that Bush was in town for a Silicon Valley fund-raiser, Bradley's appearance still commanded attention from local and national media.

Many of them were there to get a response to the surprising announcement that his campaign had raised more money than had Gore's over the last three months, and has more money in the bank than the Gore campaign. In typical fashion, Bradley downplayed the news. "I don't think we have momentum," Bradley said. "I think we have a little traction."

It's still a far cry from the pomp and circumstance of the motorcades that accompany Gore, and it doesn't quite compare to the scores of television cameras that routinely follow Texas Gov. George W. Bush. But Bradley has proven skilled at forcing the media come to him. He is cashing in on the momentum of his impressive fund-raising totals. As the vice president's campaign struggles to get off the ground, Bradley is planning two more major policy speeches while he still has the attention of the fickle media.

During his campaign kickoff in his hometown of Crystal City, Mo., the former Olympic gold medal winner and NBA star told a story about the countless hours he spent alone in the gym working on his shooting. This is the approach Bill Bradley has taken to running for president. Watching him, you get the sense that campaigning is simply a matter of repetitive motion, a mechanical exercise to be repeated over and over until he gets it right.

The persistence of the Bradley campaign has allowed him to stave off a once-inevitable Gore endorsement from the AFL-CIO. While the Bradley camp is under no illusions about the likelihood of an eventual labor endorsement for Gore, campaign spokesman Eric Hauser said the signs thus far have been promising. "They didn't endorse last winter when Gore thought they were going to, and they didn't endorse in August when Gore thought they were going to. It just shows that people are beginning to listen and that we're making progress."

Clearly, the days of the stealth Bradley candidacy are over. While Gore's attempts to label Bradley the front-runner seem far-fetched and contrived, there is no question that the Democratic race is generating as much if not more interest than the Republican presidential primary. Of course, it wasn't supposed to be this way. Gore has lobbied hard to inherit the political support President Clinton has enjoyed, but he's had a rough go of it thus far.

But will all this attention benefit Bill Bradley? Is he being set up to be knocked down again when his spacy, not-quite-ready-for-prime time persona is broadcast live? Or will voters thrill to the reality of an honest candidate who doesn't bother to hide his big-picture wonkishness, his disdain for back-slapping and his utter unsuitability for the 24/7, sound-bite-driven, all-gladhanding-all-the-time pace of the modern presidential campaign?

It's hard to get a handle on Bradley. He simply doesn't move at the pace of a modern-day politician. Like Oakland Mayor Jerry Brown, he has a reputation for being something of a political philosopher and not having much patience for detail or down and dirty legislating. But Bradley has none of the frenetic energy of Brown. Even Gore, for all of his stodginess, is more personally animated.

Bradley is certainly not without charm. It would be easy to imagine him with a loyal, quasi-cultish following if he were a college professor. His deliberate style and deadpan wit just seem more suited for the classroom than modern-day presidential politics. When a reporter asked him about a recent remark by Gore to the effect that the difference between him and Bradley was like the difference between Coke and Pepsi, Bradley quipped, "I always thought of myself as diet wild cherry."

And though his awkwardness with people has been well-documented -- he is not a "feel-your-pain" politician à la Clinton -- Bradley is not under the pressure Gore is under to be like Clinton. It helps underscore the undeniable fact that while Bradley and Gore have both admitted to past marijuana use, Bradley could pass for the first true stoner president.

Bradley is often described as disconnected and aloof. It is not an arrogant aloofness, just, in the words of one Democratic political operative, "weird." California Democratic campaign consultant Steve Gray-Barkan said Bradley tried to change his image as "an ideas guy" over the course of the last election, when he set up his own political action committee to raise funds to help Democratic congressional candidates locked in tough races.

"That's a pretty common tool, and it's a good way to earn some political loyalty and debt," he said. But when Bradley went to stump for Democrats in those races, Gray-Barkan heard stories of his unorthodox political presence.

"The way he communicated with people face-to-face wasn't typical," he said diplomatically. "It wasn't that people felt he was distant. Everyone felt like he was thinking about what they were saying, but there was something sort of absent-minded professor about him."

Even in the midst of fairly fawning media coverage of late, Bradley's essential strangeness is coming through. In Time magazine's glowing cover package on Bradley, "The Man Who Could Beat Al Gore," the hagiographic headlines and photo gallery are a little undermined by Eric Pooley's honest report. He describes Bradley at his climactic campaign moment to date -- his kickoff speech in Crystal City, Mo., "visibly withdrawing, pulling back into himself ... looking bored and distracted one minute, uncomfortable the next."

Pooley goes on to describe him ignoring his second grade music teacher, "gaz[ing] into the distance, even forgetting to thank her as she goes by -- until his wife, Ernestine Schlant, elbows him and he hauls himself out of the chair and gives the old lady a hug."

A similar Bradley was on display as he sold his health-care plan in a roundtable discussion in Oakland Thursday. He shook hands with all present with the somber mien of a eulogist at a funeral. With his grim, policy-wonk face on, Bradley listened to the crowd's health-care concerns, prefacing his remarks with questions like, "I want to get a context for the world you're operating in." This is not your typical presidential sound bite, but it's pretty standard for Bradley. His idea of a joke was warning the crowd, "I have one question -- but it has five parts."

But many of those in attendance Thursday praised Bradley's new $65 billion health-care proposal, even while quibbling with details. "I commend him for putting the idea of universal health care back on the table," Berkeley resident Susan Tom. And with two more major policy speeches set for later this month -- an Oct. 7 speech in New Hampshire about work and families and an Oct. 21 speech in New York on child poverty -- Bradley is doing what Warren Beatty says he might maybe sort of want to do. Bradley is the only non-Christian conservative in the race who is actually moving the debate on key policy issues.

The two-horse race for the Democratic nomination has allowed Bradley to trudge along, playing tortoise to Gore's hare. While candidates in the jam-packed Republican field must struggle to differentiate themselves, Bradley has the luxury of a two-man race. Democrats who are simply curious about alternatives to Gore are finding their way to Bradley.

But to most Democrats, Bradley is just that -- a curiosity and a cipher. While he may be hard to pin down, however, there is little doubt about his sincerity. People who have spent time with him one-on-one consistently marvel at his grasp of issues. But the people who are turned on by Bradley are normally an eclectic bunch. John Vasconcellos, a state senator from San Jose and one of the state's most liberal and eccentric legislators, said he decided to endorse Bradley after an hour-long conversation in the car with Bradley last summer, driving between the Bay Area and San Jose.

"He exudes dignity," Vasconcellos said. "He has the vision, integrity and authenticity to be a great president."

Vasconcellos also applauded Bradley for his promise to make race the centerpiece of his campaign. "He's like Reagan was with communism. In every Reagan-era policy, there was always the thought of how is this going to affect the Soviet Union. With (Bradley), the question is "how do we deal with race?"

But for all of Bradley's focus on race, it is difficult not to notice that he is surrounded by a campaign team of all white staffers. Oakland has large, politically active African-American, Asian and Latino communities. At a reception after the town hall meeting there, Bradley was greeted by more than 200 overwhelmingly white supporters.

This is not to question Bradley's sincerity on the race issue. It is obvious from reading his 1996 memoir, "Time Present, Time Past," and talking to people who know him well that the issue is close to his heart. But the abundance of white faces listening to a candidate talk about racial reconciliation makes the speech feel like a college lecture, an abstract principle not enforced by reality.

And while Bradley has eroded what was supposed to be Gore's fund-raising advantage, he still has a lot of work to do. Bradley has apparently pulled even with Gore in two key states -- New Hampshire and New York. But in California, the nation's largest state and a key piece of Bradley's early campaign strategy, the former senator still lags in the polls.

California Gov. Gray Davis is a friend of the vice president and has already endorsed Gore. The state party, led by former state Sen. Art Torres, is firmly in the Gore camp, as are many of the state's Latino leaders, including Lt. Gov. Cruz Bustamante and Assembly Speaker Antonio Villaraigosa.

But three months ago, Bradley's campaign seemed a long way from the cover of Time magazine, too. Clinton-Gore fatigue could make this anti-campaigner the perfect candidate. As he told supporters in Oakland, "You don't want momentum in the second quarter. You want it in the fourth quarter." He and Al Gore could be fighting over who's the underdog until the final buzzer.

Shares