The scene creeps in again, dog-eared.

Julian is almost a year and a half old. The furniture is pulled away from the southern corner of the living room, where his babysitter, Liu Yen, practices Chi Gung each day. When I come home, Julian is lying in her lap. She holds his hand with the pink palm up.

"How was he today?" I ask, tossing my bags and kicking off shoes at the same time.

"Oh, OK," she says, looking at her slippered feet.

She is still mad about our conversation yesterday. That must be it. I had told her for the last time that Julian must not go in any cars without his car seat. It's not only dangerous, I told her, it's illegal. I had tried to make my ultimatum less personal, less my own neurotic mothering. Liu Yen didn't like being told to do anything. It's why she married a younger man, a taboo in her culture. It's why she took part in the demonstrations in Tiananmen Square. It's why she left China.

"Is anything the matter?" I ask.

Liu Yen speaks softly, but her eyes are direct, sure in their gaze to the floor, then to me. She holds Julian's fat little starfish hands that never stop grasping at things.

"I have thought many times to leave here," she says.

She had been a chemist in Beijing, an apprentice to a scientist researching traditional Chinese medicine. She is precise, intelligent, spiritual. I was drawn to these qualities and to her warmth, her laugh, the way she lifted Julian from my arms the first day she met us and distracted him from a cry by taking him to the window. "See baby? See the bird. Ah yah." He was transfixed.

Now Liu Yen opens Julian's hand and strokes his palm.

"You are lucky I have stayed so long. It is too much responsibility." She says "responsibility" slowly, getting every syllable right.

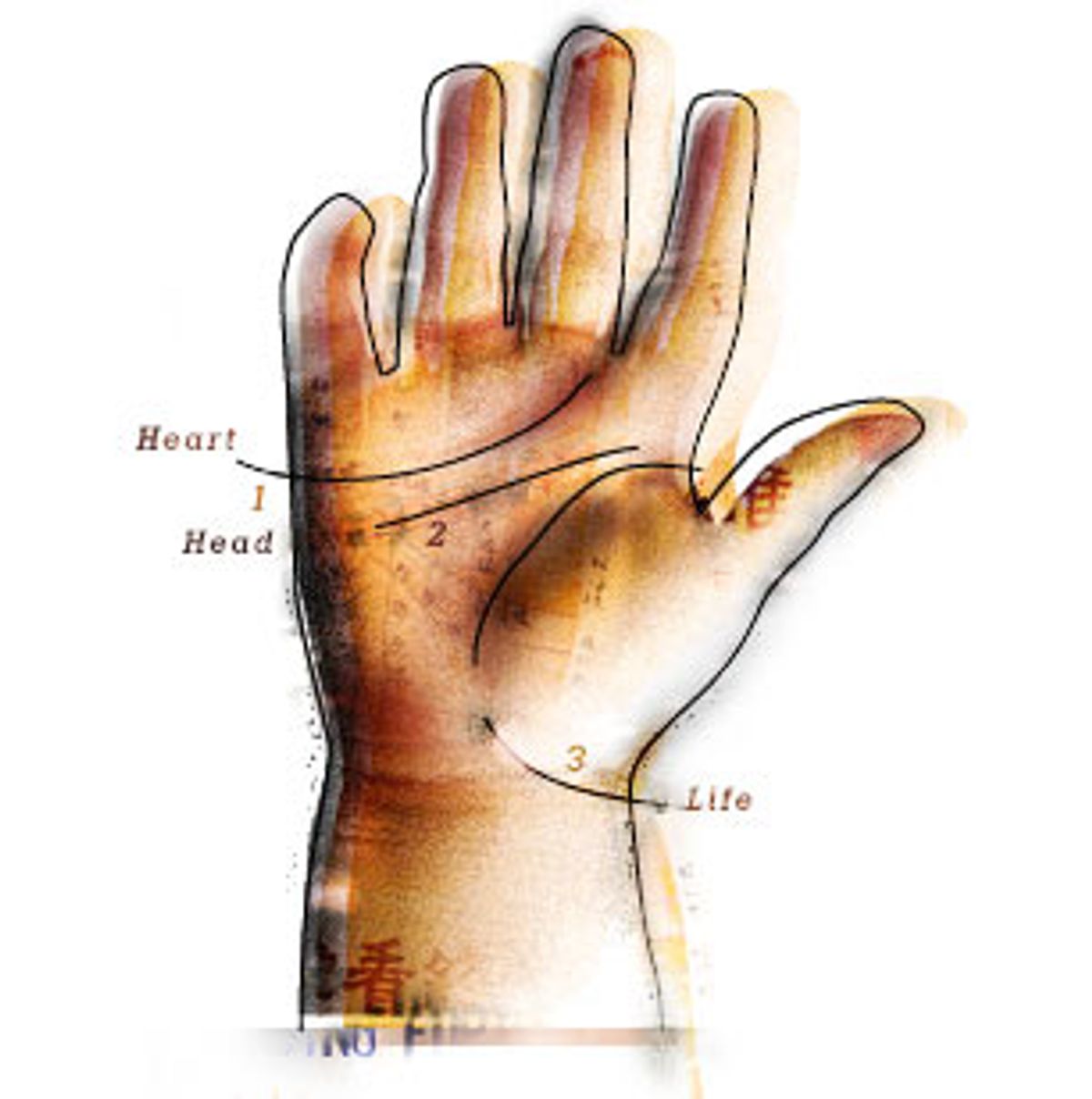

"You see," she says, looking down into his palm, "his lifeline is broken. It stops here."

She looks at me. I don't understand.

"Whenever that happens," she says, "there will be a terrible accident. I knew a girl who fell out of a third-floor window, and another, worse ..."

I think I am smiling.

"But he will not die." She lifts his hand. "You see?"

I am nodding.

"The line continues over here. But there will be an accident. That is why I can't ever take my eyes off him. I sit by the cradle when he sleeps."

When Liu Yen left for the day, I moved Julian from my hip to my heart and held him with both arms.

In the midst of this sort of trauma, the kind that breaks your faith, not your bones, things happen in slow motion. Fear brings astounding clarity to detail. Vision narrows to prevent sensory overload. When I was 15, a friend told me she was pregnant. She told me how they told her at Planned Parenthood. They said to her, "The test was positive," and she was thinking, "positive, that means good. I'm not pregnant." Then they said to her, "That means you are pregnant." She remembers those words and the dent in the silver coffee pot with the black handle that sat on a small table across from her.

I remember flickers of that afternoon with Liu Yen: Julian's hand in hers, the sofa with its pattern of bronze squares stamped on brown cotton. Between us there is something. I imagine that she has tossed me a stone, and I can't catch it. It's a rock that in traversing the arc between us grows bigger and heavier. I start taking steps backwards, sensing the weight of it coming toward me, trying to figure out how I'm going to hold it when it lands.

Six months later, in the July heat, we tethered balloons to the fence for Julian's second birthday. Inside, twisted streamers crisscrossed the ceiling and the dining room table was pushed to one side of the room and covered in a paper table cloth. I can't remember what was printed on it. I remember the tablecloths of other years, talismans of his changing passions: farm animals, pirates, the Beatles. Maybe I don't remember this one because there were no pictures taken for his second birthday party. We left the moment it began.

We heard the first guest: It was his best friend, Coleman, with his parents. At last! Julian ran out to see them. As soon as he reached them and knew that the party was really going to be now, he turned and ran toward the house, a blur of blond. I turned away to reach for a bowl of chips to bring outside. Then I heard the wail, one of those screams that follows a too-long delay of breath after the thunk of a crash.

Then blood. Blood was pouring out of his mouth. I dropped the bowl and ran. Held him. Felt his blood soaking through my shirt. Brought him inside. Tried to calm him. Get a towel! I don't know what happened! Calm him. He is arching his back. He wants me. He doesn't want me. People are coming in. His grandfather, my father-in-law, laughs. It's one of those tales we'll tell, he's already thinking. OUT! My mother shoos my father-in-law with a gentle arm behind his back. My own father, Julian's other grandfather, slips up the carpeted stairs. There is nothing he can do.

We apply ice, and things begin to slow. His face is red from blood and tears and fear and rage. He is on my lap all this time, all these four minutes, maybe five. I can see: His tongue is still whole, but his lower teeth have gone all the way through his lower lip. His father, by nature so calm, raises his voice. Fucking shoes! He yanks the brand-new navy blue sandals from Julian's feet.

And I'm thinking, is it bad enough? Is this swelling gash across his lip the break in his line, the empty section in his palm? And as soon as the thought comes to me, I know it isn't. It's going to be worse.

Over time, I allow Liu Yen's prophesy to fade from my maternal consciousness. It recedes, and I relax, only to have it lurch forward with the unsuspected force of an earthquake.

Riding home from school when he is 5, Julian says, "Mom, I have a choosing question for you and you have to pick one."

"OK. Shoot."

"If you have the choice, if you could fly like a bird or swim like a fish under water for as long as you wanted, which would you choose? And you can't say 'either.'"

"Give me a minute," I say. "OK. Flying."

"Not me," says Julian, "I'd choose swimming, because then I'd get rid of one of my deaths. I could never drown."

A temblor of memory jolts me to readiness. It could happen anytime.

Only once did I tell friends, fellow mothers, about Liu Yen's prophesy. They checked their own palms. Only one had a break in her life line. "Look at this," she said, full of reassurance, "and here I am, still alive." But what she was forgetting and I was remembering was the haunting story she'd once told us about how, while traveling in a foreign country, she was raped at knife point.

When he is 7, I hold a private vigil at circus school, sitting on an icy concrete bench, watching Julian's body fly in a great arc on the trapeze that, like a sinking pendulum, slowly lowers him to the safety net. The pendulum weights time, and I hold my breath through every slow swing, every stretched second.

I keep meaning to ask Wendy how often they check the circus school's trapeze, how recently they have inspected the condition of the lines, the riggings, the metal spools over which the lines slide as spotters pull, hold, and release. Watching Julian on the trapeze, I calculate the effect of one of the ropes jamming or splitting. It's the remaining rope that would do the damage. It would send Julian in a 45-degree trajectory outside of the safety net. If one of the spotters is distracted by a voice calling, a fly on her neck, what happens to the rope? Is there a safety catch that would hold? When Julian lands, I exhale.

A few weeks after circus classes began, I get a phone call. "There has been an accident. We are closing the circus school until further notice -- to check the equipment, make sure it's safe." Later I learn that an accident, through no fault of the school's, caused a young woman's death. I try not to think of the prophesy, but when I look at Julian I think: For now he is safe. There is more time.

For Julian's friend Mila's 7th birthday, she has a gypsy party. The girls are barefoot, all bangles and flowery skirts, with eye-shadow, rouge and lipstick calling attention to their innocence. Julian is a 7-year-old buccaneer in short black pants, one of my scarves wrapped around his waist, and his black felt pirate vest on top of one of my white blouses. A torn and faded blue bandana is tied across his forehead, blond spikes sneaking out.

After I drop him off, the fortune teller pulls up in a beat-up Datsun. I watch her wrangle herself and all her gear out the door of the car. She wears a colorful flouncy skirt, a white peasant's blouse, and jewelry that sings with gold coins. She also wears sneakers and carries a boom box.

Mila's parents tell me later how the children watched in silence as she turned the tarot cards. They were rapt as they listened to her describe who each child was and what might become of them.

"I am a knight!" Julian swoons when I pick him up. "I don't remember his name, but he discovers important things. He's also a leader," he says, "I think."

His bandana is turned around so that the knot is over one eyebrow, and his vest is half torn off his shoulder. He is breathless, running up the stairs and into our house.

"And see this?" he says, holding up his hand, palm to me. "I have a lifeline on my hand."

I breathe.

"Here, give me your hand. I'll show you yours," he says, opening my hand, then without looking, turning his eyes to his own.

I wait.

"But see this?" he says. "Mine stops here, then it keeps going over there. That means I'm going to have an accident or something someday."

Another breath.

Halfway through a box of raisins he looks up, into the space above his head and says to no one, "Maybe I'll discover something really good. Maybe I'll find some treasures."

I haven't seen Liu Yen since she left for school eight years ago. But the stone she threw is close enough now for me to see its pitted surface. There is a crack through its middle, and a shard has flown into Julian's hands. He caught it without so much as a scratch, and I watch the rest of it spin through space, lighter now, flawed now, and within my reach.

Shares