The unseasonal heat in the San Francisco area the past few weeks has reminded me of when I lived outside Athens, when I would wake up and my whole body would feel sluggish, drained, hung over from the heat of the night, a heat that draped over me like a toga.

I'm sitting here in the bone-warming sun in Berkeley, surrounded by students, as I was so often at the school where I was teaching in Greece, and that whole long-ago year is rushing back to me -- all the wonder and mystery and discovery of my days there, fresh out of college, half of my lifetime ago.

Ah, Greece. I had boarded the Orient-Express -- the real Orient-Express, not the tarted-up private version that now runs under that name -- after a post-graduation summer in Paris, and chugged through increasingly unfamiliar landscapes until suddenly I awoke to the dry rocks and dirt and dusty green trees of Greece. It had seemed forbidding at first, worlds removed from the blue mountains, lush hills and flower-bright fields of Northern Europe. Yet what wonders that world held -- and still holds -- in my mind.

Everyone should have a year like this, a year that opens up the world for them. I arrived in September thinking I would go to graduate school and eventually teach comparative literature at some ivy-laden East Coast university. Ten months later I left to ride Arabian stallions into the Sahara Desert, climb Mount Kilimanjaro and enter a creative writing graduate program to practice poetry.

What was it about Greece? I re-read my journals and letters from that period, leaf through the books that meant so much to me -- the magic and madness of John Fowles' "The Magus," Henry Miller's incomparably romantic, exuberant "The Colossus of Maroussi," Lawrence Durrell's sensual and poignant "Reflections on a Marine Venus," translations of Cafavy, Seferis and Kazantzakis -- and try to puzzle it out.

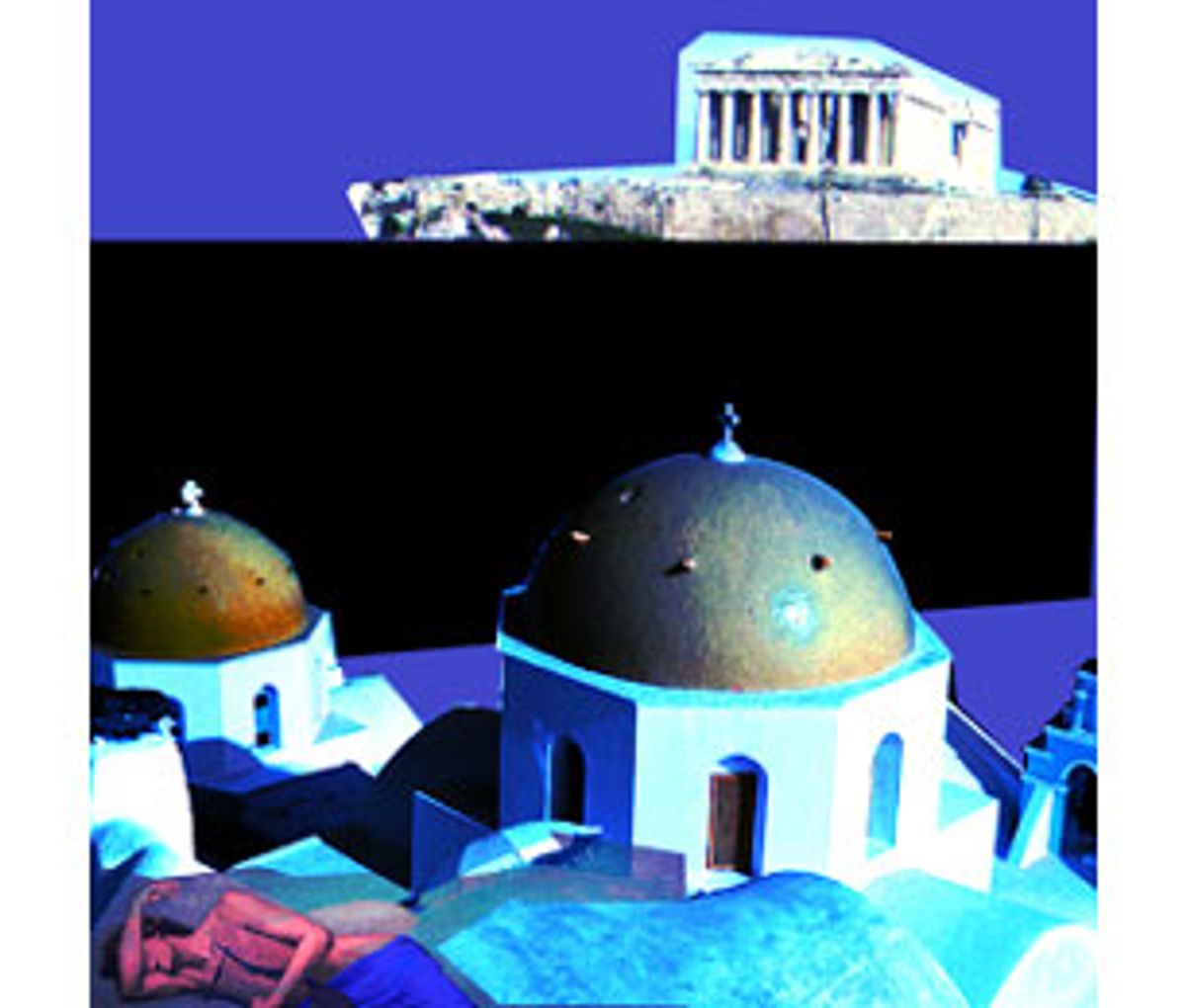

What I remember best, now and always, is the light. It was dazzling, dizzying in its clarity, a kind of clarity I had never seen before. That Grecian light demarcated everything, wrote the landscape in capital letters . Each rock was ROCK. Each branch was BRANCH. And when, a few days later, I climbed breathless and in awe to the Acropolis, each column was COLUMN.

The light was rugged and pure in a way that, after a while, made the land seem equally rugged and pure -- and the people, too, free of artifice, solid, rooted. I remember the extraordinary kindness of so many people all across the land: the teaching colleague who would habitually spend his entire monthly salary the day that he got it, taking me and the three other young American teachers out for a night of retsina and plates of mezedes delicacies under the stars; the families that spontaneously invited me to join their children's wedding festivities on Crete; the mothers in mountaintop villages who would sweep me into their homes, feed me honey cakes and show me albums of their relatives in America; the painters and poets whose love of words and colors and lines overflowed in ouzo-fueled conversations until dawn.

If I close my eyes and sweep my brain clean, I am there again: It is late afternoon, classes are over, and I have just returned to the campus apartment I share with Jeff, another teacher at Athens College in Psychico. As usual, Jeff is sitting at the room's sole desk, a glass of retsina in one hand and an ancient Greek text in the other. Jeff is a student of ancient Greek, and his idea of a good joke is to walk into a small downtown shop and ask for a bar of soap or a loaf of bread in Homeric verse.

The antiseptic apartment -- really one sprawling room with two beds at one end and the desk at the other -- has cream-colored walls and earth-tone bedspreads and tiles that the dormitory maids scrub every day. The room's sole saving glory is a balcony that looks over the Attic plain, and after I put my books away, I pour a glass of retsina and pull a chair onto the balcony, and Jeff and I watch the sky turn peach and pink and purple and slowly fade into star-pricked blue, and talk about the philosophers and poets who watched the light fade centuries before.

This is one of the things I love about Greece, how the past and the present walk together, how the Greeks speak of their ancient artists and thinkers as if they were still alive and you might see them at the taverna the next day. The Greeks don't live in the past; rather, the past lives in the Greeks. And this is true of the gods, too. They dance through casual conversation as if they were neighbors, and eventually you get the impression that the everyday Greek is intimately acquainted with the deities.

"Greece is full of magic," I write in my journal, and I am thinking of Dionysian nights on

moon-drenched beaches, of sunset toasts on terraces overlooking the wine-dark sea, of fried fish at beachfront restaurants and simple feasts of cucumbers, tomatoes and feta cheese. I am thinking of ancient spirits at Sounion and Knossos, of living mosaics on Delos, worldly monks on Mount Athos, spine-charging connections at Delphi and Olympia and Mycenae.

Now I am sailing into a tiny island harbor town late at night. Strings of lights are festooned along the waterfront, and their reflections dance on the dark water. The raucous plangent sounds of bouzouki music emanate from the open-air cafe on the waterfront, and men sit in squat wooden chairs around small tables arguing and laughing, raising their glasses and singing, flipping their worry beads in their fingers. As I get off the ferry, a wizened, rotund woman in black waits to ask if I need a room. When I say yes, she leads me through a maze of twisting alleys up and down past whitewashed walls on rocky streets until we come to a scrubbed doorway; she enters and then waves me inside. She leads me to a tiny, spare, immaculately clean room with a compact single bed in one corner, a basin for water and an old chest of drawers. It is late and though the lights on the waterfront are alluring, I unroll my sleeping bag on top of the bed and crawl into sleep.

The next day the woman writes her address on a slip of paper and I stuff it in my pocket. I spend the day exploring the bone-white ruins and bleached beaches at the far end of the island, then around dusk find my way back to the waterfront, where the whole town seems to be out for a stroll, the scent of souvlaki spices the air and the old men who were singing at the waterfront cafe yesterday invite me to join them for a drink of ouzo. The glass arrives crystal clear and then they pour a little water in, not too much, and it becomes a misty swirling waterfall and the taste is chalk and licorice and sharp and crisp and cooling after the heat of the day.

Glasses are poured, and island tales -- mingling gods and ancestors and the black-capped fishermen at the next table -- are brought out like heirlooms and polished until they gleam. More chairs scrape up and soon plates appear -- octopus and eggplant and who-knows-what -- and at some point the crowd around our table grows and grows until it seems to encompass the whole waterfront, and then people are dancing and singing and finally plates are being thrown with wild abandon to smash into star-shards in the Aegean night.

Some time later, after a few final toasts of eternal friendship, I stumble into the cobbled streets and follow the whitewashed walls until I realize I am hopelessly lost. With a mind as misty as ouzo, I think about pulling the sky over me like a blanket and falling asleep to the swashing lullaby of the sea. Then a search-and-rescue party of my evening's hosts, worried that I might be wandering the labyrinthine alleys until dawn, finds me and guides me to the doorstep of my new home -- Kyria So-and-so's place, which they know because they saw her greet me at the ferry the night before.

When I wake up in the Grecian heat, I am thinking about puzzles, how Greek villages are like puzzles, and about Greek ruins, and the things we decide to do with our lives. A day in Greece is a puzzle, and so is a year -- and so is the fact that things that happened to me half a lifetime ago can live inside me as if they happened yesterday.

I look at the letters and journals and books around me, and think: The stars and the ouzo, the ruins and the revelers, the beach and the unquiet sea -- when we are open to them, they impart a kind of grace. And when we are ready to receive them, the ancients and the gods walk with us, and the pieces all fall into place.

Shares