"Like all those who never use their strength to the limit," Colette wrote, "I am hostile to those who let life burn them out." Fiercely disciplined, hugely productive, the author of "Gigi" and "Chiri" lived 80 years and produced nearly 80 volumes of fiction, memoirs, journalism and drama. She married three times, had male and female lovers and for a time supported herself as a mime, dancing semi-nude in music halls throughout France. When she died in 1954, she received the first state funeral the French Republic had ever given a woman. And she created the subtlest, most sustained literary examination of love and sex that we have.

An initial reading can be perplexing, though. Colette is a strikingly elusive writer. Packing her books with delicious clothes and furniture and ravishingly attractive people, she delivers pleasures that most "women's writers" only promise. But her prose is rarely straightforward or transparent, and her characters -- captured at the height of their beauty or in beauty's humiliating decline -- maintain a mocking, self-protective reticence.

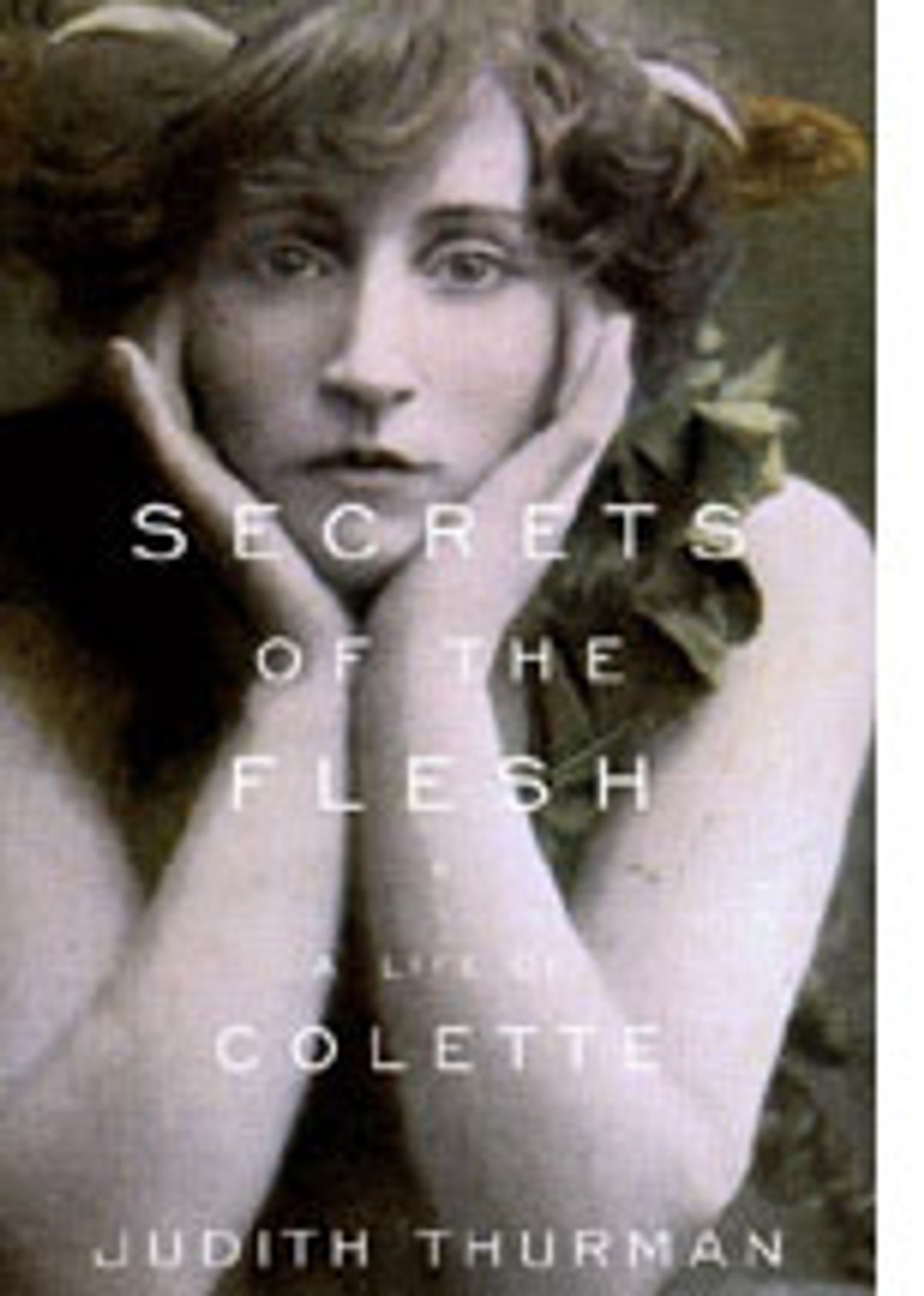

"Secrets of the Flesh," Judith Thurman's superb life of Colette, guides the reader with great assurance through a wealth of complex material. Thurman won a 1983 National Book Award for "Isak Dinesen: The Life of a Storyteller." A gifted literary biographer, as sure-handed as her subject, she never conflates the life with the work or allows her admiration to interfere with an informed and delicately balanced critique of Colette's uniqueness.

Colette, Thurman says, was "remarkable among modern writers -- perhaps the great women in particular -- for a sense of self not vested in her mind." Maybe female writers have simply had to think harder in order to carve out space within ideologies that would otherwise have shut them out: Witness Doris Lessing's communism, Simone de Beauvoir's existentialism. Colette, on the other hand, seems to have missed most of the intellectual action that animated European politics during her lifetime. "There was not an idea that could carry Colette away," says Thurman, "or a sensation that couldn't."

She drew inspiration from entertainers, courtesans, an aristocratic Parisian lesbian subculture and the fin de sihcle gay aesthetes whose "fetish worship of human beauty" she shared. She admired the bravery of lives lived on the sexual edge, the consciously chosen tastes and prejudices, the risk of physical danger. Her understanding of gender was far ahead of its time; her treatment of sex between generations can still make us uneasy.

Thurman describes Claudine, the heroine of Colette's earliest fiction, as "this century's first teenage girl: rebellious, tough talking, secretive, erotically reckless and disturbed." Claudine marries a man 25 years older than she in a sensually saturated pulp wishdream of love as eternal childhood. Contemporary fans couldn't get enough of her: The books and product spinoffs (Claudine cigarettes, chocolates, clothing) were huge sellers. The books are still fun, but their darker themes remain undeveloped. Claudine's marriage is too much like the long, blissful summer vacation Dolly Haze must have thought she'd be taking with Humbert Humbert.

For Colette's most powerful examination of cross-generational love one turns to Chiri, the story of an affair between an elegant woman of 49 and a young man of 25. The novel explores a passionate attraction that's simultaneously selfish and self-sacrificing, controlling and terrified of losing control. Lia's love for Chiri is both sexual and maternal, a seductive, disturbing combination that leaves both partners incapable of being satisfied by anything simpler.

Courting dissatisfaction in love, Colette's characters nonetheless do so within one of the most satisfactory physical worlds ever depicted. Dominique Aury (who under the pseudonym Pauline Riage wrote "Story of O") remarked that Colette never neglects to describe her heroines' meals or the comforts, grand or shabby, of their bedrooms and bathrooms. Her interiors have the plenitude of gardens, and she writes magnificently of food, flowers and animals -- not analytically but, as Thurman says, "from the point of view ... of the child first 'sorting out' her paradoxical instincts and experience."

A less happy immaturity was the intellectual and moral passivity that allowed her to publish in pro-Vichy, anti-Semitic journals during the Nazi occupation, even as she fought devotedly (and successfully) to keep her Jewish third husband from being deported. It's one of the great virtues of Thurman's biography that she deals unsparingly with Colette's tin ear for moral principle, locating her complacencies within contemporary French social history and popular opinion.

There's one point on which I would have liked Thurman to be more complete. It's a relatively frivolous one, but still, I'd hoped to learn what Colette was actually doing onstage during those pantomimes for which she was so adorably dressed as a faun, a cat or an Egyptian in a jeweled bra. How long were the performances? What part did words and music play? Was anybody doing anything except striking poses, preferably with some clothes torn off? The publicity photos for these shows look pretty awful, and it remains unclear to me what might have prompted a leading aesthete to call Colette's performance "a day of art at the theater."

This almost-quibble aside, "Secrets of the Flesh" is a fiercely intelligent and accomplished book and -- using the words with all due weight -- an immense pleasure.

Shares