I never saw a gun until I was 24. I didn't grow up in Mayberry; I grew up in Southern California. In my old neighborhood, drugs and alcohol fueled many parties and fights. One night, my younger brother and his friends had an altercation at the end of the street; from my bedroom windowsill, I watched them run home. A boy named Sammy had a knife; someone hit him in the head with a baseball bat. He was killed.

In junior high, where I met my future husband Dwayne, we witnessed mass fights and riots. I saw girls with razors in their hair and boys with fists. There were more riots in high school; boys fought viciously, one with a tire iron. Fights could be brutal; our friend B.D. got his jaw broken over a quarter in a parking-lot craps game. But no one was killed in school, and no one had guns.

Dwayne had seen guns in his neighborhood. Many fathers there, originally from the South, still hunted. On New Year's, they shot guns in celebration.

But Dwayne never had a gun. When we were newly married, hanging out at my longtime girlfriend's house as drugs really exploded in our city, Dwayne was terrified when my girlfriend's husband pulled out a semiautomatic pistol from under the couch. A potential customer, or killer, had knocked. I was upstairs with my friend and her new baby.

Later in the car, Dwayne told me we couldn't visit them again. "He pulled out a piece. We can't take that chance," he said. "Could be the cops. We could get caught in a shootout." He shivered, I remember clearly, and said, "I heard him cock that baby. Click, click."

Thirteen years later, a shotgun fell on my head as I searched the closet for baby clothes, and my heart leapt in fear, like a small animal tethered to my breastbone. Dwayne hadn't told me about the shotgun, never mentioned we were armed. I suddenly imagined him holding the gun, cocking that baby. Shuck, shuck.

Since college, Dwayne had been working with juvenile offenders at a correctional facility. Many of their crimes involved guns. When I was five months pregnant with our first child, Dwayne worked graveyard shift. One night, a juvenile pretended to take an overdose of stashed pills, and Dwayne had to escort him to the hospital. A man jumped from the bushes and shot Dwayne in the chest with a Taser stun gun. Dwayne staggered, but his size, his sheepskin jacket and his bravery blunted the shock. He punched the man, knocking him down, and ran after the hobbling juvenile headed for a van. Then another man emerged from the van, pointing a .38 at Dwayne's face. Dwayne had no choice; he had to back away.

He didn't tell me. He didn't want me to faint, to upset the baby. But I read about the escape in the paper and then I saw the burn marks on his jacket. When he described what had happened -- to me and later to the court during trial -- I heard what bothered him most: the unfairness of the gun. Bravery and size and loyalty don't match up with bullets.

I confronted him about the shotgun, after gingerly laying it on the floor. I knew nothing about bullets or shells or what the heavy black weapon might do. Dwayne sighed. He said our city had become increasingly unsafe, with car-jackings and drive-by shootings and random violence. He'd gotten the shotgun for protection, for the intruder that might break into our house. He would be ready to protect us -- his little family. He would be a good husband and father; repelling evil was his job.

But I saw him fall in love with the guns themselves, the seduction of the barrels and oil and wooden stocks with carving, the power of caliber. He bought a handgun, then another, and spent hours comparing weapons with our next-door neighbor and my brother. Our neighbor, a very conservative guy, had gleefully told us that he thought a burglar had tested his bedroom window one night. "All he has to do is put a finger over the sill, and he's inside the threshold of my property. I can blow his ass away. It's my right."

My brother acquired his first gun when he was very young, from a recently-fled drug dealer's residence. Now he lived in a rural orange-grove area, and he shot at coyotes who killed his animals, and at drug runners who used the groves for transport. Sometimes he joked that he only shot what moved.

Dwayne began shooting at the range, and shooting in the groves with my brother. Even my brother was impressed when my husband bought a Chinese-made SKS assault rifle. "How many rounds would it take to kill a possum in the yard?" I joked. But I was scared. I didn't want anyone pushing on my window screens, but neither did I want the burden of a dead person lying across the sill.

The guns themselves fascinated me for a short time, but underneath my curiosity I was terrified. I never learned to shoot them like the neighbors' wives, who went to the range. Instead, I opened the oven and there they were, baking at a low temperature as part of the cleaning process: a 9 mm handgun, the shotgun.

Dwayne spent hours in the garage cleaning and oiling them and making his own ammunition with a reloader. He spent hundreds of dollars on weapons, bullets and accessories. Hobbies are expensive. But these were weapons. Not for play -- they could only shred targets or skin and bone.

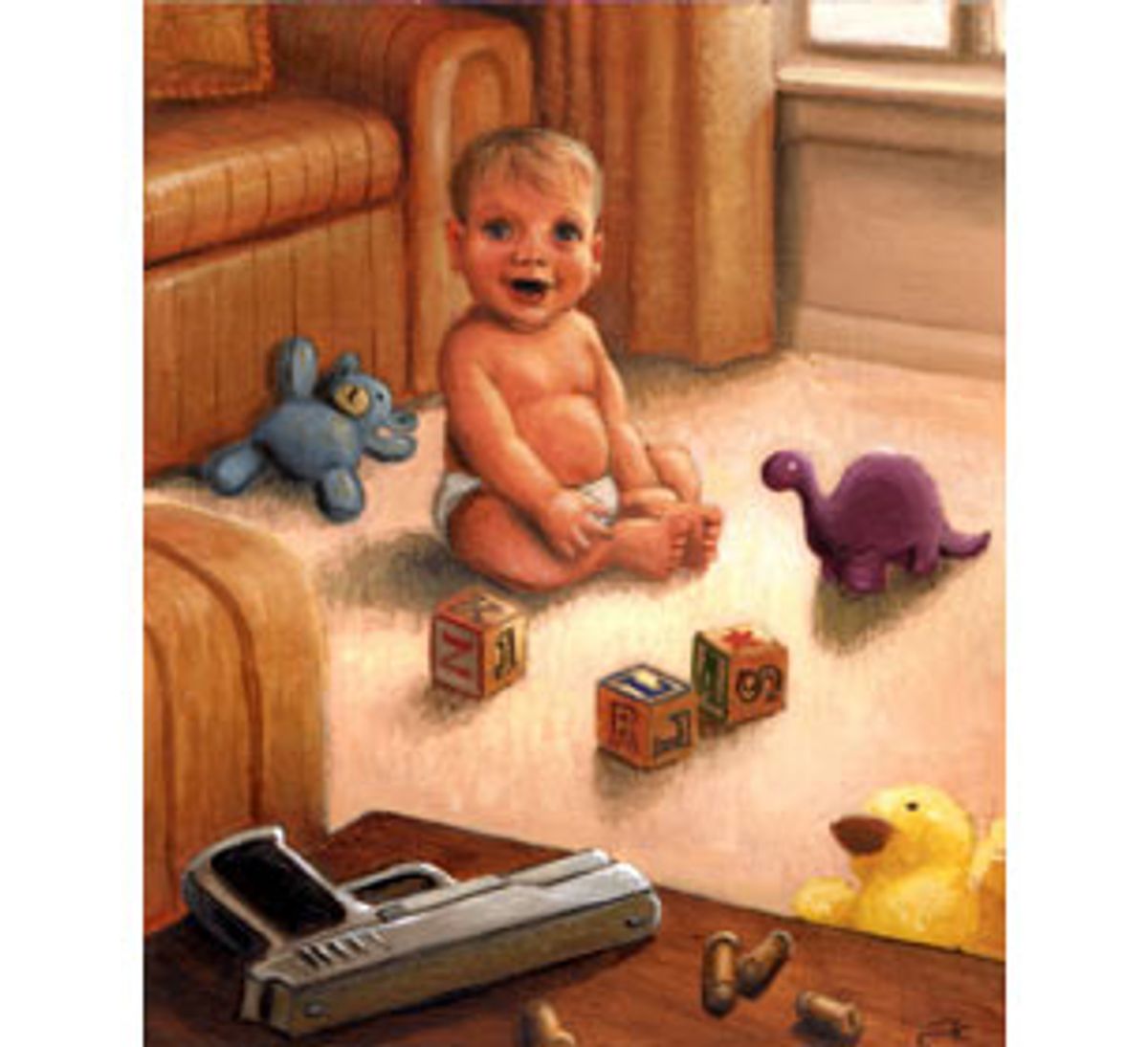

"Only a shotgun, for intruders, and the shells are somewhere else," I'd been told that day, after the closet. But then I found a handgun on the dresser under a knit cap, within easy reach of our daughters. There was a gun in the camper when we took vacations, a gun in the glove compartment of the car. All those years, I'd been afraid of the police stopping Dwayne, a black man, and now I was even more scared, because what if they saw a gun in the glove compartment?

Every night, while I graded papers, Dwayne was in the garage making shells or sorting bullets or oiling a gun barrel. I watched him, I asked him about the guns and I wrote about them in my last novel. I imagined being a teenage boy, surrounded by gangs and death, who falls in love with weapons as defense; who cannot kill but who cleans and stores and loads the guns to protect his own sanity. But my imagination was still afraid, and when I knocked on the closed wooden door, very late, my husband answered wearing his 9 mm in a shoulder holster. Who was I? Was I on the threshold?

We had three children, and suddenly he had 10 guns. I didn't feel protected. I felt like I was living with a different man, one who didn't play basketball and read Sports Illustrated like before, one who baked his guns clean and read Guns & Ammo. Our house and garage and vehicle, my spouse, carried instruments of death. The 9 mm handgun on the dresser, shockingly heavy to me, could have been picked up, dropped, fired, by fingers smaller than mine. And I couldn't forgive that.

When we visited our old neighborhoods, drugs and guns were everywhere. Our girls approached the car of a childhood friend and I saw an Uzi on his front seat. The stubby barrel was barely hidden. I nearly screamed. A relative had a derringer, tiny and palm-sized, in his car. When I finally told Dwayne I didn't want to live like this, he replied, "This is real life." But I didn't want it to be my life, my children's lives. Guns and his work and this real life had engendered a paranoia, a mistrust, a secrecy and a fatalism that I couldn't share.

On our last walk together, without the kids, we took a trail in the nearby river bottom, a place we'd explored as children. Stepping down a narrow path through fall-browned brush and wild grapevines fallow for winter, we saw in the tall bamboo a homeless encampment where dogs barked at us from the entrance. Then we were in a clearing near the water, and a huge snort came from the arundo cane. Feral pigs lived there, though we'd never actually seen one. They can weigh 200 pounds, tusks included, and they've charged riders on horseback.

Dwayne pulled a 9 mm handgun from his back waistband and aimed toward the cane. I was amazed. "Back up," he whispered. We both did. The snorting was grumpy, not enraged, and then the cane trembled as the pig crashed the other way.

I stared at the gun. "So you were gonna shoot the pig?" I said, and Dwayne tucked the gun under his shirt. "And when that pissed him off, he was gonna charge the littlest person -- me."

"I didn't bring this for wild pigs," he said unapologetically, as we walked back. "I brought it for wild people."

I know he's right -- the wild people are out there, but inside my house, there are no wild people. My daughters hate guns. They hate seeing guns in constant advertisements for movies, and on TV news, which in Southern California often consists of freeway chases ending with drawn guns, or videotape of convenience-store robberies where people wave guns. They hate their uncles' guns, and they hate their father's guns.

Is this because I've told them to? Because they're girls? No. It's instinctive fear. I'll never forget volunteering in a kindergarten class, sitting near the circle of children while they talked about a book. Then a boy said his dad's gun could have killed the monster. The teacher said, "Guns are scary." She looked shocked. "How many people in here have seen guns?"

I drew a quick breath when my middle daughter Delphine raised her hand, along with nine or 10 other kids, and said, "My dad has a gun in his car."

"Mine does, too," the first boy said. "It sits on the seat next to me."

The teacher glanced at me, incredulous, and I was ashamed. For all of us.

My daughters are afraid of pit bulls, of the stranger waiting to kidnap them. I was afraid of those things; I still am. But my kids are truly afraid of guns, of their presence everywhere.

This breaks my heart: that they are so young and know too much. I have a desk drawer full of bullets. Yes. I have found spent ammunition on my sidewalk, and several years ago a teacher at the girls' former preschool poured 10 bullets into my cupped hand, her eyes full of tears. She said her 10-year-old son was given the bullets in their apartment complex, encouraged to get a gun. She moved to North Carolina soon after that.

I have 10 of Dwayne's bullets in the drawer, too. He lives a short distance from us. One night at dinner my youngest, then 2 years old, mentioned the gun she'd found under the couch at Daddy's house, and then Delphine frowned and mentioned the two she'd seen under the bed. They'd been playing hide-and-seek.

I felt twinges of pain between my hipbones, where my babies rested inside me, where fear always circles for me now. "It was only a BB gun," Dwayne said when I called him, immediately, angrily, incredulous. "And the rifles were in a case."

"Well, OK, and I'm glad she has that third eye in her forehead for when the other one gets shot out," I said.

For me, saying, "You'll shoot your eye out with that thing" is not a joke. I know a woman blind in one eye from BBs shot by siblings. On the phone, I went ballistic. I went postal. Gun phrases, now an integral part of our culture.

I told him the kids couldn't visit under these circumstances, and we argued for days. I said I didn't care if the guns had only been stored under furniture temporarily. I still remembered the dresser, the glove compartment. And now, a year later, the guns were stored in a locker at the foot of his bed. The girls whisper to me that they hate sitting on the blanket-covered metal chest. "It's scary to sit on the guns. They're in there."

The shotgun, the same one that clunked me on the head, is hidden in my house -- the one that started this whole thing, the one Dwayne left behind when he moved out. "So you can protect yourself," he said when I called him about it. (A year after he left, I got on a ladder to vacuum the moldings and found more than 30 cartridges stored around the room, beneath the ceiling, where he could easily reach them.) I haven't loaded it; I don't want to know how. I have held it, looked at it in the mirror, made that shuck-shuck sound, put it away.

My children are my life. I don't want scars anywhere on their bodies or in their brains and hearts. The way parents were afraid of polio in the 1950s, scared of public pools and free-floating germs, I am afraid of guns. I picture anonymous gun barrels while I wait outside the chain-link fence at school, while I walk across the store parking lot where someone was shot a few years ago.

Was my mother ever afraid of bombs like this, after surviving World War II in Switzerland? Was my father-in-law afraid after surviving Depression life in Oklahoma?

All his relatives had guns. I remember watching westerns with him years ago. "There's the Colt .45," someone would say with reverence. "The peacemaker," someone else would chime in. "Tamed the Wild West." But Dwayne's father would reply, "All we ever shot in Oklahoma was dinner squirrel or rabbit." He never had a gun, other than an ancient hunting rifle, which Dwayne keeps in his collection.

People hunt people now. That's the difference. That's what Dwayne was trying to say, over and over, to me. How did we come to this, all of us?

I am afraid of the wild people, just as he is. And when I think about a wild stranger touching my children I even wish, briefly, for a handgun. On our strolls to 7-11 for Slurpees, I watch everyone passing us on the busy street, on the eucalyptus-lined sidewalks. I plan what I will do to a possible attacker. I admit it -- I visualize "the great equalizer," the peacemaker, the one thing that would make me, 5-4 and 105 pounds, able to repel anyone who tried to hurt my girls.

Then do I understand how Dwayne feels? Do I understand how any of them feel -- husbands with guns or boys like the two I saw outside my living-room window, comparing handguns and then tucking them into their waistbands before getting back on their bikes? A gun gives anyone all the power in the world. Here in America, the most powerful country in the world, we have the most guns of all. And we are all, almost all of us, afraid of each other.

In my bedroom, perched high in the moldings, there are probably stray green shotgun cartridges. Somewhere in my house, tucked away, is a shotgun. I don't think of them as protection; they don't provide any relief. I think the gun was one of my ex-husband's favorites, left behind as a phantom guard in his absence.

Maybe it makes him feel safe.

Shares