Classic, film-noir amnesia -- bewildered victim awakening in a hospital room with no sense of self, no memory of a name or of the events leading up to the present, dependent for clues on nurses and policemen and others claiming (but surely only pretending) to be family members: This sort of amnesiac state is almost completely a fiction. It is the stuff of movies and novels, a reliably suspenseful narrative device and a metaphor richly evocative of human experience but in fact hardly a human experience at all. Amnesia in the clinical sense is usually something much less absolute (and often quite temporary) even at its worst.

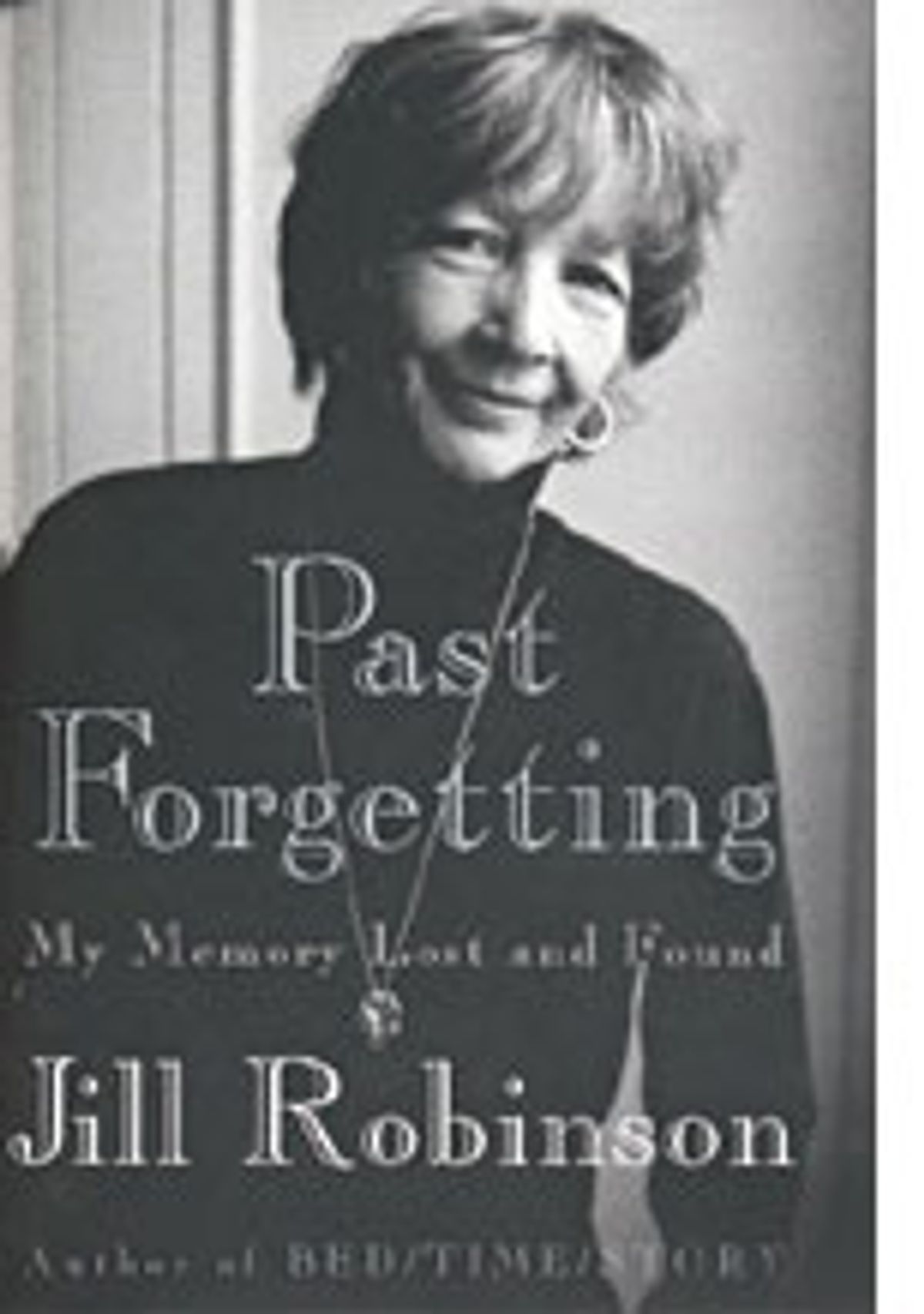

Odd, then, that "Past Forgetting," a gemlike, seductively readable and quietly moving memoir recounting that great rarity, a truly encompassing and persistent loss of memory -- in this case caused by a swimming-pool accident -- should be written by a woman whose life involves so many fairy-tale elements and is populated by so many movie stars that if it were fiction it would seem ludicrously trashy. The novelist Jill Robinson ("Perdido," "Bed/Time/Story" and many others) is the daughter of Dore Schary, who, when he replaced Louis B. Mayer at MGM, became legendary as the only screenwriter ever to be handed control of a movie studio.

Robinson spent her childhood and early adulthood at court with Hollywood royalty. This is a woman who grapples for memories of her childhood and comes up with snippets of conversations with Cary Grant. She conveys an impression that celebrity is a way of life -- a given, like sky or water, to be puzzled over only in philosophical asides. When she reconstructs a crucial period of dissolution in the '60s and early '70s (she writes with great insight on the texture of the counterculture), her partners in crime are Dennis Hopper and Bob Rafelson, Los Angeles art stars David Hockney and Ed Kienholz, and so on.

None of this stargazing detracts from the center of her narrative: the amnesiac writer's poignant groping, with her husband's patient, infinitely caring assistance, for an understanding of who she is, of how her children have grown and her parents have died and of how she came to be living in England when she knows she's never been on an airplane. Her struggling brain has crushed together her two marriages and mingled her children's childhood and her own. She cringes daily in anticipation of chastening phone calls from parents long dead. Her strongest remaining impressions are of the '70s.

Most strikingly, she recalls the vast emotional importance in her life of the act of writing, without remembering anything of the methods or the discipline writing requires, nor of what she would write about if she could. It is of course through her writing that she eventually recovers not her memory but her self. In a language at once conversational, aphoristic and deeply nuanced, Robinson shows herself coming to understand that even before her amnesiac rupture she was really only constructed of postulates, of stories, of moments; that memory is an illusion and a dance -- one she can rejoin if not reconstruct.

Two-thirds of the way through the book, she is lured out of her introspective convalescence by an assignment from Vanity Fair to search out the victim of a famous Los Angeles rape. The sequence at first threatens to derail the book but grows in interest until it becomes an analogical double for her memory quest and an exploration of the meaning of Los Angeles in the long aftermath of the '60s. It reads like a collaboration between Dominick Dunne and Steve Erickson; if, in Ezra Pound's famous dictum, literature is "news that stays news," then Robinson's accomplishment here might be described as gossip that stays gossip.

The emotional peak of her story comes late in the book, when she arranges a reunion with a certain grade school acquaintance, a boy who, despite his kindness, was daunting, distant, impossibly attractive and stirring in some way she has never quite resolved. She isn't certain he'll remember her at all -- her amnesiac condition is so absolute and infiltrative that she constantly attributes it to those around her and to the world at large -- but he greets her on the phone with familiarity and warmth. They meet and speak of childhood and self with vast sensitivity, and when Robinson finds a part of herself restored, the reader thinks: It isn't only amnesiacs who need to commune brilliantly with the most beautiful person of the opposite sex from grade school -- I need this, too!

The friend in Jill Robinson's book is Robert Redford.

Shares