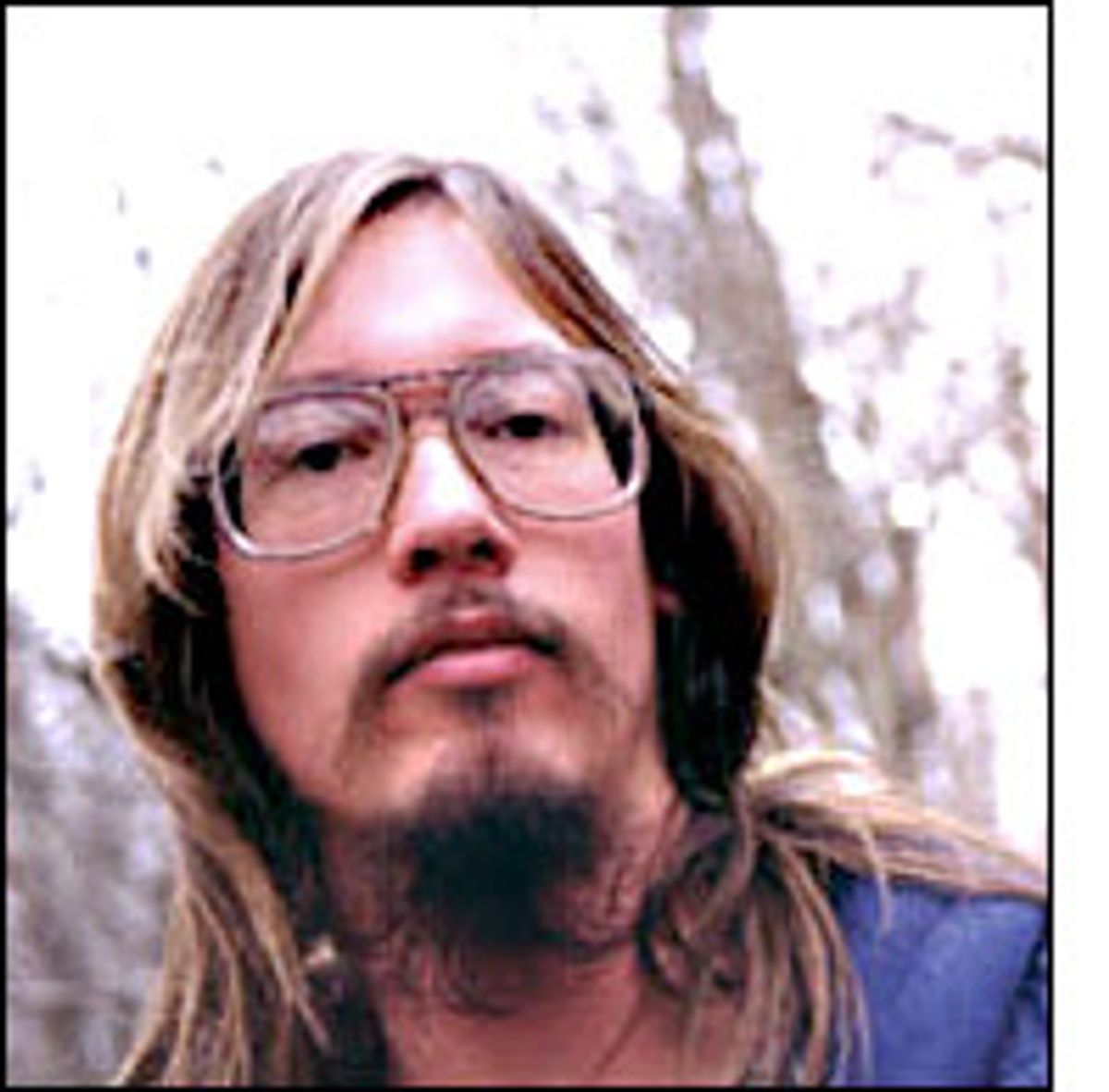

The cameras may have stopped rolling on Mark Borchardt, the Milwaukee filmmaker and star of the recent documentary "American Movie," but his story continues to unfold.

"American Movie" director Chris Smith spent two years following Borchardt in his quest to complete two films, "Northwestern" and the horror short "Coven." With unflinchingly honesty, Smith's cameras focus on the dude-ish indie filmmaker, his loyal sidekick Mike Schank and an assortment of wonderfully wacky friends and family members. As Borchardt's dreams overextend his funds, he ropes in friends to be film extras, employs his mother as a camera operator and drives an aging uncle to the bank so that he can become an "executive producer."

"It was a total honor," says Borchardt of having his life captured on-screen.

"American Movie" works because Borchardt is far removed from the L.A. film scene, but the early buzz about the film has thrust Borchardt into the middle of a Hollywood circus. He's been hounded by Robert Redford at Sundance and asked for autographs; he has taken limos to screenings and been approached by "we should talk" industry insiders.

Flattered and a bit wide-eyed, Borchardt understands "American Movie" is Smith's film, not his. Over omelets and coffee at a New York diner, Borchardt talked about the surreal ride of becoming famous for being himself.

How have things changed for you since "American Movie" began showing?

I'm sitting here, talking with you, that's how it's changed. A lot of people are calling me back in Milwaukee, the phone is always ringing, it's a hassle in that sense, if you know what I mean ... I don't want to have to go to a bar and talk about projects because I've already got my own project.

I've never been on this side of the process before, that's how it changed, too, with going to Sundance, Toronto. Sitting here doing all of these interviews, being recognized and stuff. For a year now, I've been totally exposed to something entirely new, but I don't integrate that into my process of filmmaking back in Milwaukee.

This is one side of the filmmaking process. This is more the documentary-

Do you like the whole being on this side of the filmmaking business?

Yeah, of course I like it. I've never been exposed to it. But then again, I have sense enough myself not to integrate this with my filmmaking process. Because I know most people would. They'd follow up on the dozens of business cards that they've gotten. They would actually set up a deal down the road, more than likely, and I'm not going to do that. But you see, I'm 33, man, I got these films that I have to make, man, and they just don't jive with the independent or Hollywood way of making things.

By going to Sundance and Toronto, has any funding for your own films cropped up?

I've been offered some money, tentatively, but I don't want to take that up. I want to get my own money, borrow it from some credit cards, borrow from some people who don't give a damn about filmmaking so they don't want to put their girlfriend in it, or something like that. Like my dad and Bill, they'd give me money, but they didn't want nothing to do with the process, and that's the only good money to get.

When Chris was filming you, was there any added pressure, coming from yourself, to get your film finished?

Things would have happened the same even if he hadn't been there. Because [making a film], all of suddenly, it pulls you along, no matter if you have a lack of discipline or a drinking problem. The film -- you become responsible to this damn thing you created.

Chris filmed you pretty regularly for two years. Was there any point when you said, "Chris, turn off the camera, I don't want this, or that, shown"?

Nope. I trusted Chris and I knew he was investing his time wisely. And for me to start setting boundaries, it might limit him, to say, "Well, I don't think he'd want me to film this," and he might miss stuff. It may set a precedent for days to come where he may not engage in something that he should have, so no, I never said anything.

Your friends and family pulled you though. They reminded me of this microcosm of a Hollywood production team. Why do you think they were willing to help you out?

Because I had to have people help me. I had to convince them, to motivate them because I had no other choice. I treat them with respect so I think they help me out, but I help them out, too, hopefully and so one hand feeds the other.

Have your friends and family become more interested in movies now?

No, not at all. If I would never shot another reel of film, it wouldn't matter to them. They're not into film at all.

Was it difficult for you to watch some of the family footage, like when your brother says he thinks you could hurt someone?

No, that's just the way he thinks. I could care less. It just adds to the breadth of the film. I know what you mean, though. At that part, you kind of wince.

The part I winced at is when your mom says she doubts you'll make it as a filmmaker.

I didn't feel bad for me, I kind of felt bad for her that she said that. I guess you've got to watch your words, but she said what she said.

At the screening I was at, the audience was cracking up, particularly when Mike came on-screen. Some parts were genuinely funny, but did you ever feel that the audience was laughing at your friends?

No, because they're laughing at their behavior. I know what you mean, about maybe [the documentary] being condescending or patronizing, but that's not the way I see it. Because I know these people. And I think it's great to let them be up on-screen because a lot of people don't see people like that.

I never felt any malicious laughter whatsoever. You can laugh at us, or laugh at whoever you want. We're just presenting who we are, man. And if you're entertained by it, more power to the whole process.

Shares