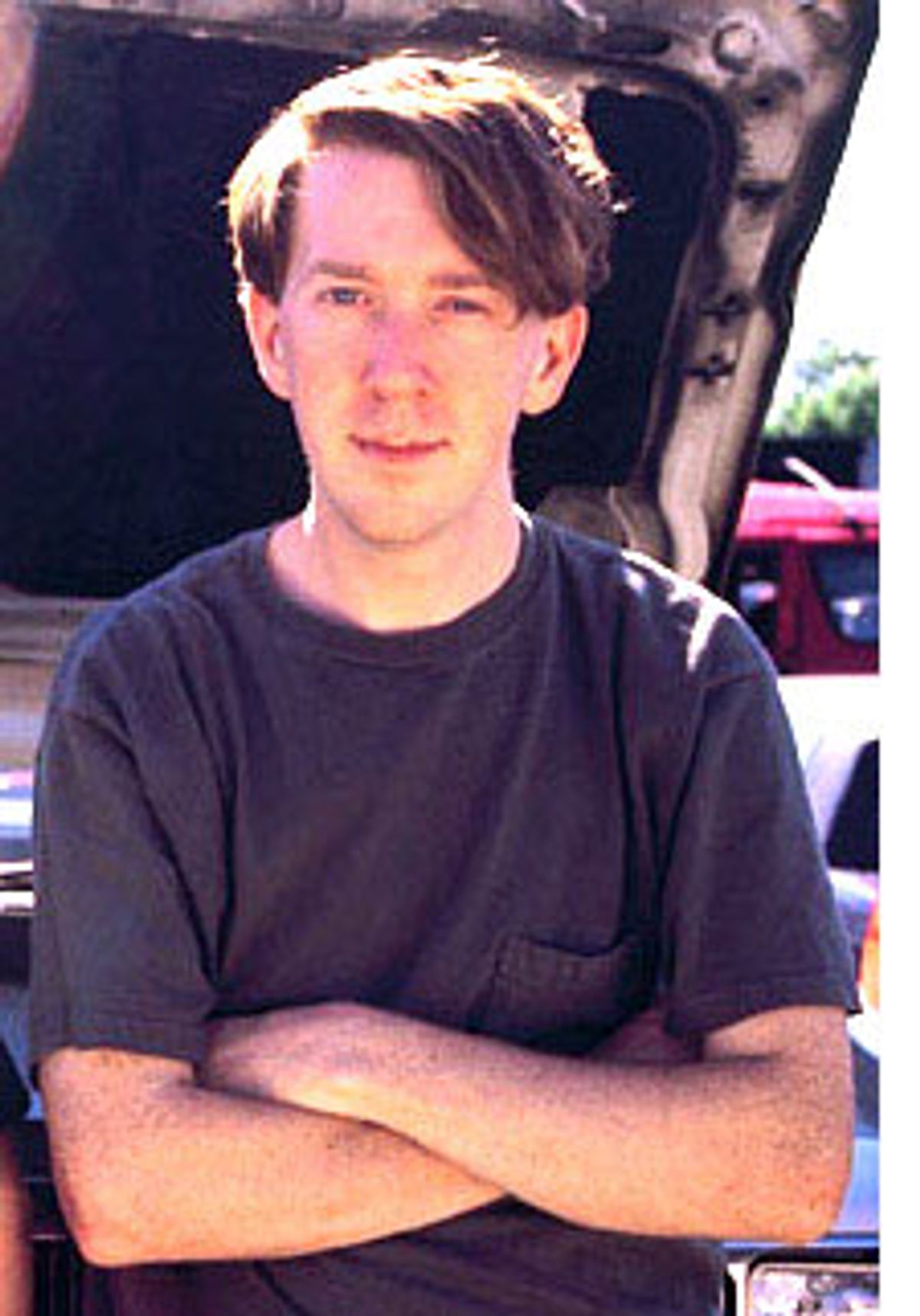

If someone were to make a film about Chris Smith, the 29-year-old director,

writer, cinematographer and co-producer of the festival favorite "American

Movie," it might go something like this: For two years, Smith -- a lanky,

soft-spoken former engineering student from Michigan -- records

the absurd misadventures of

Mark Borchardt, a beer-guzzling Wisconsin good ol' boy

and would-be auteur who's struggling to complete a low-budget slasher movie

so he can go on to make "Northwestern," the feature film he's always dreamed of. In the course of

tracking Borchardt, Smith and Sarah Price (Smith's producing partner and girlfriend) endure their own

off-screen difficulties mirroring the ones that Borchardt is having on screen.

They run out of money, plunge into debt and lose financial support. But eventually they edit their 70 hours of footage down to a nicely shaped 107 minutes, and the film is invited to the Sundance Film Festival, where it wins the award for best documentary.

In real life, the Sundance premiere of "American Movie" in January was more the stuff of slapstick comedy than of perfect Hollywood endings. Half an hour into the

screening, the sound began skipping and warbling. While the projectionist was trying to fix it, the print caught fire. A large air duct came crashing down from the ceiling, landing on 10 or so spectators. During a lengthy and unscheduled intermission, emergency surgery was performed on the print. Yet in the audience of several hundred people, only two left the theater. Afterward, the audience gave it a standing ovation. Suddenly, Smith was surrounded by a flurry of offers. "It's like having a family photo album, and suddenly someone wants to buy it from you," he recalls. A few days later, Sony Picture Classics bought distribution rights for close to $1 million.

Smith grew up as the youngest of four children in an upper-

family in East Lansing, Mich., where his father managed a plastics factory.

In high school he belonged to a group that made odd videos with a goofy, Monty

Python flavor. "I was the worst actor in the group, so I wound up working behind

the camera a lot," he recalls.

At the time, he wasn't thinking of a career in filmmaking. After high school, he enrolled in engineering school near Philadelphia before switching to art studies at the University of Iowa. There, he had access to the school's production equipment and made his first film -- an animated short about two Twinkies who flee a bakery and find a new life, which won him $10,000 in a Hostess Twinkies contest. Smith used the loot to finance his first full-length movie, "American Job," a portrait of a man trapped in a series of

minimum-wage, dead-end jobs. It was a scripted narrative film rather than a documentary,

but it had a deliberate documentary flavor, shot in cinima viriti style. It was accepted by Sundance in 1995.

Smith compares making a low-budget independent film to buying a lottery ticket.

"It's hard to tell when you're doing it whether you have the right building blocks.

You need magic to cement it together. But if you have the right elements, and you

make the right film, then you win."

The right elements for Smith included finding a university that was sympathetic

enough to his projects to give him access to film equipment. The University of Iowa

film department, for example, discouraged aspiring auteurs from making features. While Smith was editing "American Job," administrators wondered why it was taking so long -- they were under the impression he was making a 20-minute film. When it became clear that it was time for him to move on, friends suggested he try the University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee. He sent the school a videotape of his rough cut. The chairman of the film studies program loved it, and gave Smith the keys to the department. "I lived in that film department," Smith recalls. "I even slept on the floor."

Unlike Borchardt, Smith was able to find a supportive community. Also unlike

Borchardt, he and Price had access to credit cards. "Mark was never

able to get more than one credit card," says Smith. "We had nine credit cards and

ran up $28,000 on them. Compared to Mark, we had a luxury road. And unlike Mark,

we didn't have people around us saying, 'Why waste your time doing this when you

know you'll end up working in a factory?'"

Smith did, however, have to deal with people who thought he was wasting his talents following Borchardt. But Smith got hooked on the idea almost as soon as the two met in Milwaukee four years ago. "I liked him, and we bonded immediately. He has this ability to warm up a room, and I enjoyed his company. People respond to his personality, and he gets

people to help him." Indeed, what makes "American Movie" compelling is the

way Borchardt's buffoonish charm draws you in.

Still, one can't help wondering whether "American Movie" isn't entertaining its

audience at Mark's expense. We're made to feel for the guy, but that doesn't mean we'd

ever want to sit through his horror movies. (Incidentally, Borchardt's

"Coven" has been previewed alongside "American Movie" at several showings.) But Smith says he's a true believer in Borchardt's gifts. "I'm convinced he has talent," Smith insists. "I give Mark a lot of credit. A lot of people have been surprised by his competence. He has a

great eye. And if he brings it together, [his feature] 'Northwestern' could be an excellent

film."

Shares