Nonfiction

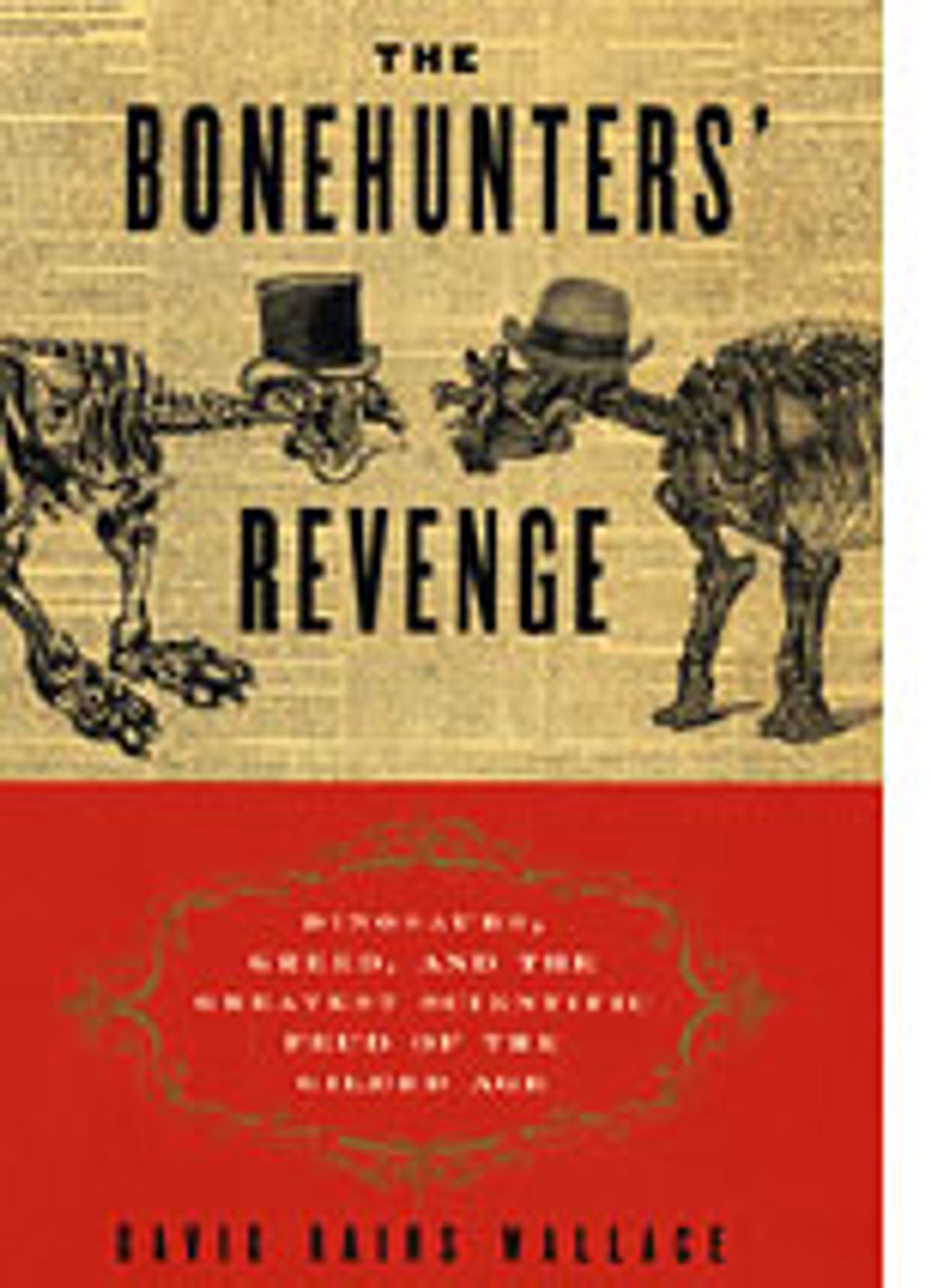

The Bonehunters' Revenge: Dinosaurs, Greed, and the Greatest Scientific Feud of the Gilded Age

By David Rains Wallace

Houghton Mifflin, 368 pages

After laboring through his book, I have a good idea what David Rains Wallace means when he remarks on the mind-numbing tedium of excavating fossils. "The Bonehunters' Revenge," an account of a bitter feud between two American paleontologists in the late-19th century, has the skeleton of a compelling story, but you have to dig through a lot of prosaic writing and pointless quoting of old letters and newspaper articles to appreciate just what a fearsome beast this rivalry was.

Although Othniel Marsh and Edward Cope were definitely of the same genus -- wealthy, WASPy Easterners who in the 1860s and '70s had discovered and named an astonishing number of dinosaurs, reptiles and extinct mammals of the Mesozoic and Cenozoic eras -- temperamentally they were of very different species.

Marsh was a man of the Establishment, deftly sucking up to the gods of academia and government to sponsor his bonehunting trips in the "great untouched cemetery" of the American West. Cope was an iconoclast, a Quaker remarkably adept at making enemies, who used his dwindling inheritance to fund his shoestring expeditions. With his bug-eyed, hyperthyroid restlessness, he was a kind of Wile E. Coyote whose best-laid plans invariably blew up in his face. (For a museum display, he mistakenly attached a fossil head to a tail.) He started his paleontology career reading the Bible around the campfire and ended it a foul-mouthed, womanizing, slander-slinging scoundrel who, Wallace says, didn't "realize there was more to a scientific success than scientific work."

You can't help liking Cope, in other words. Yet Wallace's sympathies are entirely with the smug careerists who kept shutting the door in his face. An irritant to the meticulous Marsh, Cope's greatest offense was to challenge Darwinian orthodoxy -- not to question the fundamental facts of evolution and natural selection but to ask why organisms would mutate to begin with, allowing one to become more fit to survive than another.

Gradually reduced to poverty as Marsh became one of the celebrity scientists of the age, Cope refused to be cowed. After decades of eating Marsh & Co.'s dirt, he came back at them with a series of "exposis" written for the New York Herald by his friend William Hosea Ballou ("a free-lance hack"), alleging bribery, plagiarism, incompetence and the corrupting influence of machine politics at the enormously important U.S. Geological Survey.

"MEN OF SCIENCE AGOG," one of the better headlines read. "Some Shocked, All Stirred up, by the Sensational Disclosures in the Herald." Unfortunately, the charges were all either fuzzy or ill-founded; and as no competing newspapers picked up on the scandal, the Herald quickly turned its attention to other matters. "The great scientific war had been a dud," Wallace writes.

Now it may be responsible history to admit that "the greatest scientific feud of the Gilded Age" wasn't much of a story after all -- just "an awkward, boring patchwork" of "feeble bits of journalism" -- but then why revisit the feud a century later? The answer, I think, is that no matter how petty or spiteful, the bickering reveals much about the temper of the times. And that's where Wallace is at his best, evoking the romance of science when it was still something of an art and the world was still "so recent that many things lacked names" (as Gabriel Garcma Marquez once wrote).

The professionals and specialists like Marsh, with their advanced degrees and the security of tenure, hadn't yet taken over the show. Amateur naturalists and plucky adventurers like Cope and Ballou still had an important role to play in the epic drama of discovering just what a strange and surprising world this is. Maybe they had to leave the stage kicking and screaming because they knew there would be no curtain call for them; they were quickly becoming an extinct species.

Shares