It's the morning of sacrifices, the day when blood flows like water from the

public squares.

The festival of Dasain is Nepal's equivalent of Christmas, although it spans

15 days and is defined by copious bloodletting. The October holiday

commemorates how the goddess Durga -- a wrathful emanation of Parvati, the

otherwise demure wife of the great Lord Shiva -- slew a giant buffalo-demon

named Mahisasura. In Kathmandu, the event is recalled with zealous butchery.

Tens of thousands of goats, water buffaloes and chickens are ritually

killed, their blood spurting onto black stone shrines across the Valley.

Needless to say, this is a very colorful festival -- red predominating -- and

tourists rise early for the chance to photograph the slaughter. Most

alluring is the annual blessing of the machines, where tools and vehicles of

all stripe are doused with sacrificial blood. Mechanics kill chickens,

sprinkling fresh blood over their wrenches; Honda scooters, taxis and trucks

receive their due as well. A few miles east of where I sit, a light-duty

crane hoists a hapless goat toward the cockpit of Karnali, a venerable 757 in

the Royal Nepal Airlines fleet. The goat is gently coaxed to bare its

throat. With a quick stroke of a khukuri -- the boomerang-shaped blade

carried by the Gurkha regiments -- the animal is beheaded. Blood spurts over

the jetliner's nose, assuring another year of safe passage.

After two decades of visiting the World's Only Hindu Kingdom, I rarely get

up for sacrifices. For one thing, I can hear goats being slaughtered from my

bed. For another, I've come to accept the event for what it is: a deeply

complicated form of meal preparation. I find it ironic that casual tourists

view the Dasain hi-jinks as exotic and macabre; it shows how far most of us

have strayed from our own food supply. A century or two ago, if you planned

to serve turkey or pork for Christmas, you'd butcher the beast yourself -- and

there would be a conspicuous lack of spiritual content to the event. The

Nepalese don't eat very much meat (compared with people in China, let alone

Wisconsin), but when they do, they like to have some first-hand knowledge

of where the animal came from -- and where, by the lights of reincarnation, it might be

going.

As gruesome as it may be, the wholesale slaughter that marks Dasain isn't

what's on my mind these days. I've been disturbed by a more gradual

sacrifice: that of the Kathmandu Valley itself.

During the past 20 years -- and especially since 1987 -- I've watched one of

the world's most sacred and exquisite landscapes spiral into a morass of

mismanagement and pollution. About 10 years ago, expatriate residents

squealed with delight as the first traffic lights were installed by the

Bagmati Bridge. Today the locals rev their two-stroke motorcycles through

bumper-to-bumper gridlock, Urban Survival particle filters fixed across

their faces. The commingling of rickshaw, taxi and bicycle horns used to

have a musical, almost celebratory ring. To simulate today's effect, go to

Manhattan and spread out a picnic in the middle of Eighth Avenue. The

alluring mountain views that remained even two or three years ago -- vistas of

the snowy Himalaya glimpsed between hastily erected cement buildings -- have

been overwritten with garish billboards hawking whiskey, beer and

cigarettes.

Don't get me wrong. There are still a lot of beautiful things to see and do in Kathmandu -- from the golden spires of Pashupati temple to the all-seeing eyes of Buddha staring down from the Swayambhu stupa. The problem is that the distance between them has become a

stinging hell-realm of diesel smoke and chaos. I've bitched about it before,

but never this way. It seems to me, with this latest visit, that a line of

sorts has been crossed. Kathmandu's deterioration, left unchecked, will soon

make this once-mythical Valley about as inviting as Akron, Ohio.

All this leads me to a tale about a part of Nepal that I never

expected to see touched by the tide of industrialization. In fact, I never

expected to see it at all.

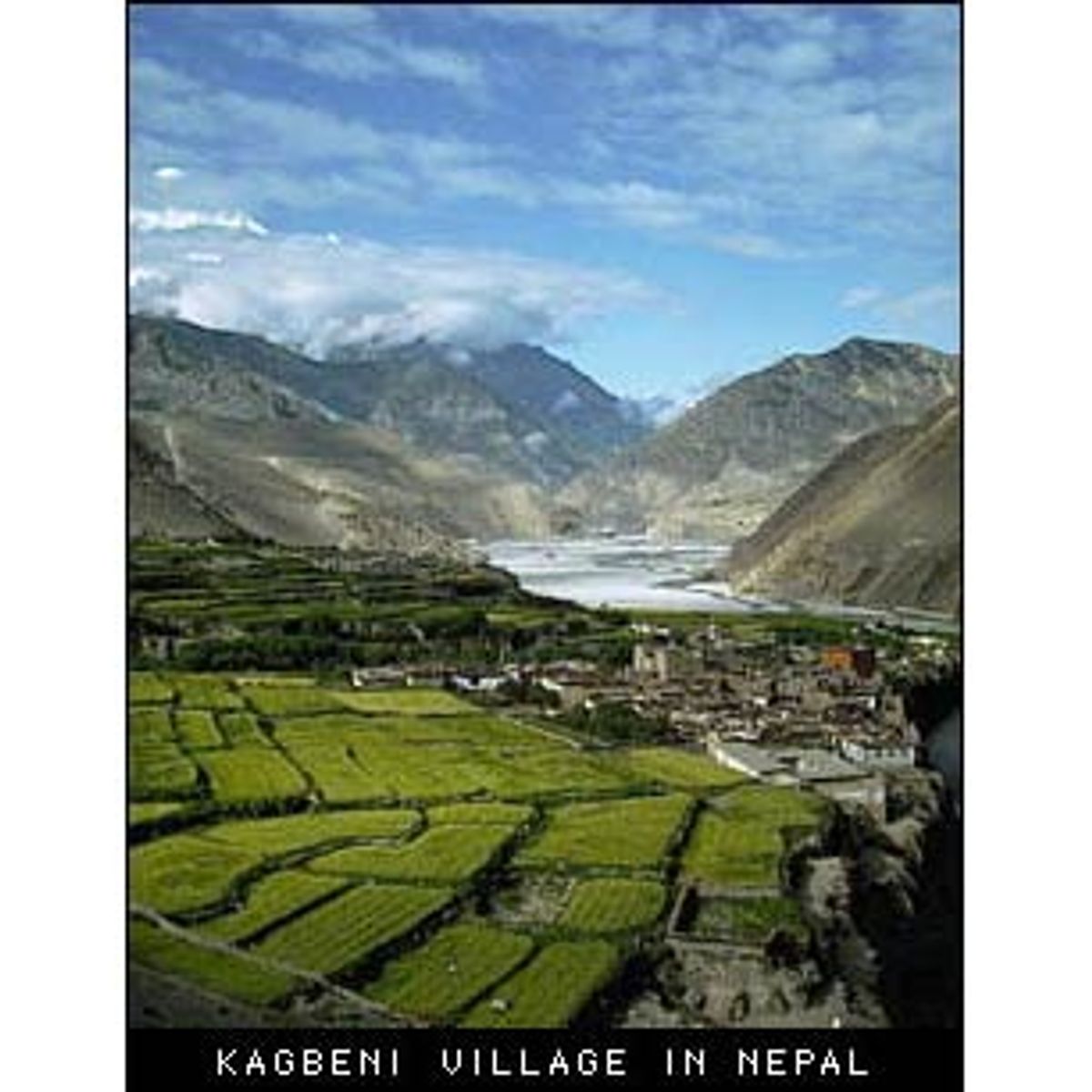

If you take a bus from Kathmandu to the lakeside city of Pokhara, and fly

from there to a Wild West frontier town called Jomson, you can walk (it

takes about three hours, up the Kali Gandaki river valley) to the village of

Kagbeni.

Kagbeni, despite the unsightly metal electrical poles lining the lanes --

"Next year," the locals say when asked when electricity will actually

arrive; they've been saying as much since 1991 -- is a charming oasis

surrounded by orchards and bisected by a swiftly moving stream. Mules and

goats traverse the narrow streets, passing doorways where elderly women card

goat and yak wool. The old Buddhist gompa has recently been restored, and

the roof provides a spectacular view of Niligiri to the east and the Kali

Gandaki to the north.

Kagbeni is the portal to Upper Mustang, an important leg of the old

salt-trading route from Tibet. For centuries the region was a small Buddhist

kingdom, with its own royalty and laws. The rajah lost his power in the

1950s, but the area -- thanks to its proximity to the Tibetan border --

remained closed. A sign at the edge of Kagbeni warned trekkers to go no farther; a

police post just below ensured that they did not.

For 20 years -- since my first trek to Kagbeni in 1979 -- I longed to

ignore that sign and continue on, traversing Mustang's harsh and spectacular

terrain: a land more similar to the Tibetan plateau than the highlands of

Nepal. The route continues northward for four days, traversing a raw and

sacred landscape before arriving at the walled city of Lo Monthang. Until

less than a decade ago, Lo was a world apart. Few Westerners had penetrated

its secrets, and entering the gates was like traveling back to the 15th century.

Nepal opened Upper Mustang to trekking in 1992. Even so, the restrictions

are daunting; visitors must pay a $70-per-day fee, with a minimum visit of 10

days. In managing the region, Nepal seems to have taken a note from

neighboring Bhutan -- where a $250-per-day fee keeps the backpacking hordes

at bay, and assures a minimum impact on the indigenous culture.

One month ago, I was finally able to make the journey to Lo. The trek

through Mustang was unforgettable; it's a place where the drama of the

landscape dovetails perfectly with the local mythology. Walking beneath a

wall of tortured, blood-red cliffs, there's little doubt that this was the

site where a bloodthirsty demon was eviscerated. The high passes and

plunging canyons teem with immortal protector deities. Spartan meditation

caves, cut at impossible heights on sheer cliff walls, make it possible to

accept that adept monks and lamas can actually fly.

Geologically, the area is equally fascinating. Imagine Zabriskie Point, or

Canyonlands. Now raise the landscape two miles high, paint it every color of

the rainbow and stretch the brutal formations under 50 miles of

periwinkle sky. Look down, though, and you're in for a shock: Intricate

fossils lie scattered among the stones, reminders of the incredible fact

that this lofty terrain -- much of it more than 12,000 feet above sea level

-- was once an ocean floor.

Lo Monthang, when one finally crests the pass, looks like the promised land.

Buckwheat and barley fields stretch beyond the ancient village, which is an

impressionist collage of white, red and gray buildings. There aren't many

materials to work with; structures are made of rammed earth, wizened

branches and stone. Crumbling fortresses squat on bare surrounding hills,

and the wind keens over aeries webbed with prayer flags. It seems, in short,

like the end of the world.

This is why it was so shocking to learn, from a handful of well-informed

locals (over a few glasses of the local rakshi, in Chimmey's Coffee Shop),

that Lo Monthang is now endangered by the very plague that has ruined

Kathmandu. Within two years, the Nepalese government hopes to build a

highway into Lo Monthang -- and turn the once-forbidden city into another

gruesome sacrifice.

The rationale for the road is deceptively simple. A day's walk south of

Kagbeni, the Thakali villages around Marpha grow a phenomenal number of

apples. This potentially lucrative export rots on the ground; there's no

efficient way to ship the fruit to the markets in Kathmandu.

Building a road south from Marpha would be prohibitively expensive -- and

probably impossible. The Kali Gandaki river valley is wild and narrow, and

the monsoon rains would wreak havoc with any manmade earthworks. So the

ethnic Thakali villagers (as well as some of the Lobas who actually live in

Upper Mustang) have decided to build a road going north -- in the rain shadow

of the Himalaya.

Present plans call for the route to begin in Lo Monthang, a four days'

walk (by porters, not trekkers) from Marpha. It will enter occupied Tibet,

and loop back down to Kathmandu on a pre-existing Chinese motorway.

Eventually the route will reach all the way to Jomson itself, crossing all

of Upper Mustang via Lo. The project will cost millions of dollars, but

hey -- everybody loves apples.

Or do they? As the evening at Chimmey's wore on, I heard some strong

arguments against the road -- and a fair amount of alarm concerning what it

might portend. There have already been a few political bones-of-contention

snafus, like whether Nepali drivers will be allowed to cross into

China at all. The Annapurna Conservation Area Project (ACAP), which manages

the area, wants an environmental impact report prepared -- but semantic

loopholes (such as the fact that the project is simply called a "farm

road") may nix this idea.

Today, with two miles of grading complete, Lo Monthang locals take it for

granted that such a road will likely be of more benefit to Chinese truck

drivers than to locals.

"When completed," a local development worker named Tenzing informed me, "the

road will make it possible for supplies like rice, timber, kerosene and

electrical goods to reach Lo Monthang from China, without high portage

charges." But whether the prices of such trucked-in goods will be

substantially cheaper than those carried by indigenous porters, he cannot

say. The benefit to the locals? "Someday, somehow," he added as an

afterthought, "the road may be used to ship wheat and fruit to China and

Kathmandu."

But even this cynical assessment may be optimistic. A former ACAP advisor was

quick to point out that, from the get-go, the chief purpose of the road will

probably be to import alcohol and cigarettes -- and to hasten any plans the

regional government may have for strip-mining.

The boisterous Tenzing, along with a doe-eyed local politician named Indra,

ticked off the reasons for the controversy over the road. There is the

possibility that the Mustang villagers will import more than they export,

turning the project into a drain rather than a benefit. There's concern that

the traditional trade for porters -- some of the poorest citizens in Nepal

-- will be destroyed. There is general unease about the "unpredictable" Chinese

having such easy access from the nearby Tibetan border. Finally, there is

the very present fear that the beauty and culture of Lo Monthang -- certainly

one of the most fascinating areas I've ever seen -- will be destroyed forever.

"If there was just one argument against the road, then OK, we'll build

it," said Indra. "But four arguments? That's too much."

Still, it seems that even articulate and influential locals like Indra and

Tenzing can do nothing to slow the juggernaut of development. The southern

Thakalis are wealthy merchants, and they want to push this project through.

Indeed, the project is well under way. The graded, two-mile section of

roadway, cutting across a bare hillside, is already an eyesore to trekkers

approaching Lo Monthang. By 2001 -- the road's possible completion --

fleets of diesel-belching trucks may completely change the cultural ecology of this

lovely and remote Himalayan oasis.

When this happens, Upper Mustang's nascent opportunity to cultivate its

sublime beauty and cultural heritage rather than its industry -- an

opportunity already squandered by Kathmandu -- will be lost forever.

"Upper Mustang has no Mount Everest," says Indra, referring to the

strictly protected status of Nepal's most famous national park. "We have no

discos or big bazaar. All we have is our walled city, and tourists come to

see it because it has been beautiful and interesting for so many years. When

the road arrives, all that will be destroyed. And why should people come

here then?"

Why indeed? One can only hope that an alternative plan -- shipping the apples

by Russian helicopter rather than transporting them for four days through

Tibet -- will grow some legs.

If not, grab your camera -- and get yourself to Upper Mustang as soon as

possible. That moment of sacrifice may have arrived.

Shares