Right from the beginning of the extraordinary documentary "American Movie," Mark Borchardt -- the do-it-himself Orson Welles of Menomonee Falls, Wis. -- is talking a mile a minute and telling us his life story. His first words, in fact, are "I was a failure." He was a talented kid with a bright future, he tells us, and he wound up at 30 as "Mark with a beer in his hand, thinking about the great American script and the great American movie." A knock-kneed scarecrow of a man, with long, stringy hair, scraggly wisps of beard and a moustache and Coke-bottle glasses, Mark certainly looks the part of a loser. When he finally gets around to some unopened mail, he finds that the IRS has put a lien on his property -- for $81. The next envelope, however, has better news: He's just gotten his first-ever credit card. "Kick fuckin' ass!" he proudly announces. "I got a Mastercard!"

A bit later in the film, Mark returns to the subject, telling us, "I don't want to be a nobody." By this time he has taken a job in a cemetery, where he shovels snow, vacuums carpets and cleans toilets. Viewed in a harsh light, almost nobody could be more of a nobody than Mark. He wants to be a successful filmmaker, but he has no formal education and no film-industry connections, and he lives with his parents in a nowheresville Midwestern suburb. His only source of funding is a senile uncle who lives in a trailer and has absolutely no faith in Mark's work (or anything else). Mark himself isn't always a likable figure -- he's an incorrigible bullshit artist who drinks too much, who is virtually buried in debt (including unpaid child support for his three kids) and who has a wide streak of self-loathing. After a spectacular binge, he berates himself: "Is that what you want to do with your life -- suck down peppermint schnapps and try to call Morocco at 2 in the morning?"

It probably won't surprise you to learn that Mark is indomitable in the face of his depression, bad luck and propensity for self-destruction (otherwise there wouldn't really be a movie here). But he's more than a lovable buffoon. Considering the quality of his work and the impossible odds he faces, Mark is evidently more committed to his craft than lots of far more successful filmmakers are. As Chris Smith and his collaborator, Sarah Price, follow Mark's not-quite career from crisis to crisis, from one dreary, working-class Wisconsin location to the next, we come to see that he's pursuing his dream with his full heart and all the capabilities he can muster. I shouldn't ruin the end of the movie for you, but let's just say that the unveiling of "Coven," Mark's 35-minute black-and-white horror film, is worth waiting for (even if he doesn't know how the word is pronounced). Perversely enough, Mark is now likely to find fame as the subject of this film rather than as the director of his own -- although viewers who are sufficiently intrigued can buy tapes of "Coven" through the "American Movie" Web site.

Smith has pointed out that Mark wasn't some college student who decided to become an indie filmmaker after seeing "Slacker" or "Clerks." He made his first movie -- a "Friday the 13th"-style slasher flick titled "The More the Scarier" -- in 1980, when he was 14. (Later on, he made two sequels and abandoned a third.) He's an omnivorous film lover who cites "The Seventh Seal" and "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre" among his influences, and you could certainly do worse. If Mark is precisely the kind of quixotic, borderline-pathological American hero that documentary filmmakers dream of, that doesn't make him or "American Movie" any less remarkable. As Mark tells the production staff he temporarily assembles for "Northwestern," his unmade and perhaps unmakable masterwork, "You're going to see Americans and American dreams, and you won't walk away depressed."

Like so many American documentaries, "American Movie" is in large part a document about class. We never see Smith and Price on camera, but even though they are also struggling, no-budget Milwaukee filmmakers, it's clear that there's an unbridgeable gulf between them and Mark Borchardt. Smith and Price are middle-class bohemians with modest cultural capital; both have worked with Michael Moore and on other indie documentaries, and Smith's first film, "American Job," played Sundance in 1996. Except for his three years in the Army, Mark Borchardt has been in Menomonee Falls the whole time, drinking, getting high and making movies called "I Blow Up" and "The More the Scarier III." When he needs privacy to write, Mark drives his 1982 Mercury Zephyr to the Milwaukee County small-plane airport and sits in the car writing on a legal pad.

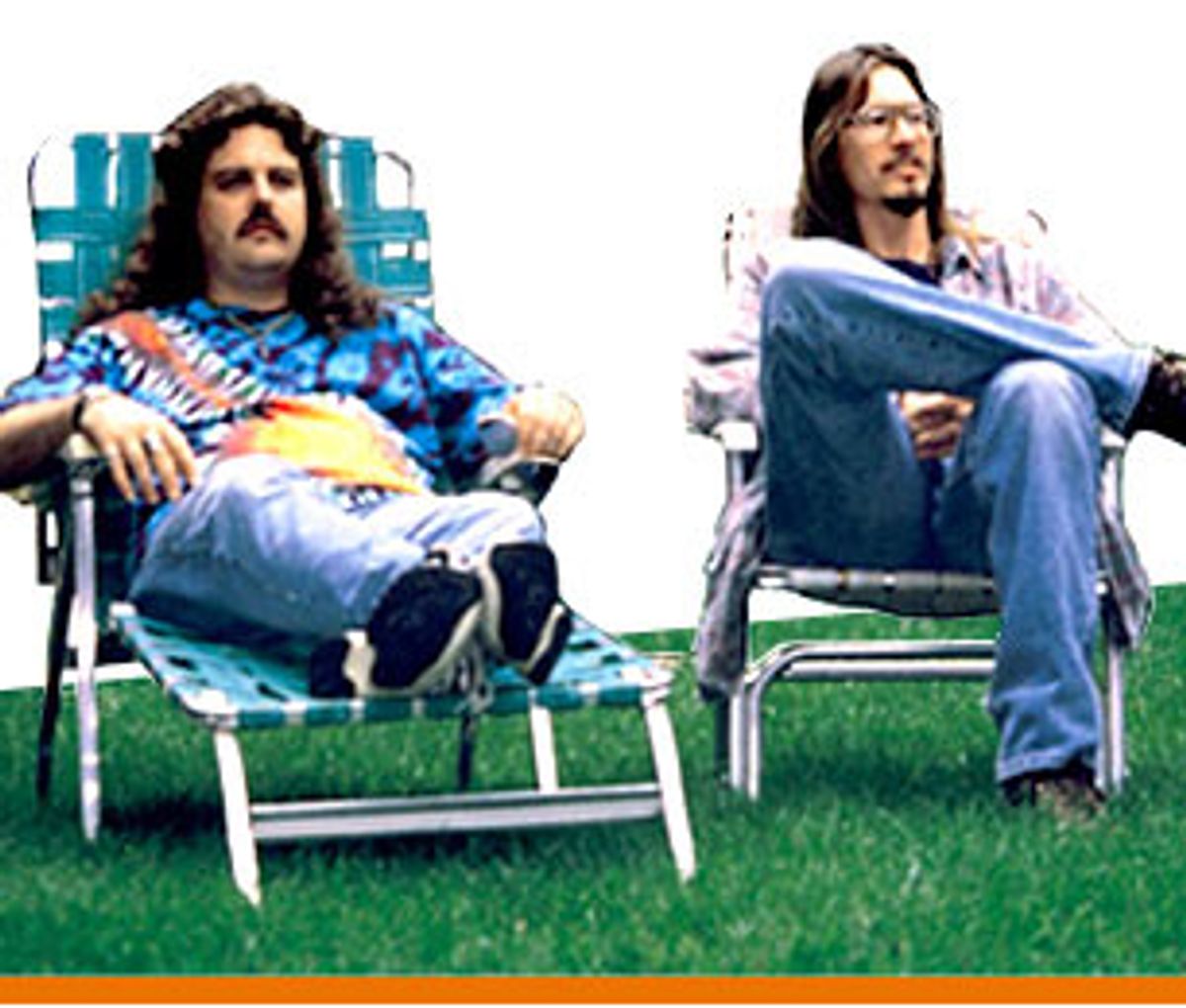

As for the cast of characters around our budding auteur, I can only fall back on the hackneyed observation that truth is often much, much stranger than fiction. There's no other way to account for Mark's friend Mike Schank, a gentle, bearlike man who can play classical guitar blindfolded and who has a very troubling laugh. Mike recently put an end to his partying days by joining A.A., but during the course of "American Movie" he tries (and apparently fails) to deal with his burgeoning addiction to lottery scratch tickets. Mike's role in Mark's filmmaking career is mainly to stand around with a blank expression on his face and good-naturedly take orders. During the filming of a crucial scene in "Coven," Mark barks at him: "You've seen a lot of movies, right? Do you know how to frame a shot?"

Mark's Swedish-born mother gamely volunteers as an extra and camera-person when needed, and his father is a genial absence (except when he complains about the language in Mark's movies). But Mark's two brothers view his filmmaking career with unconcealed hostility. Their cruelty is partly understandable -- Mark has the randomly expanded vocabulary and motormouth social skills of an autodidact, and was undoubtedly a bossy, demanding, constantly irritating sibling. Mark's real family, besides the inscrutable Mike, includes his remarkably normal and capable girlfriend Joan, along with the misfit troupe of small-town actors he assembles for "Coven" and the abortive "Northwestern." (Mark's greatest failing as a director is probably his inability to tell good acting from bad -- but then, if you ask me, most Hollywood directors have the same problem.) Most important of all is the embittered, toothless Uncle Bill, from whom Mark has somehow wheedled money.

Mark expends more than 30 takes trying to get Bill to say one final line of dialogue that will complete "Coven." Still full of energy and enthusiasm, Mark urges, "You have to believe in what you're saying, Bill." Bill shakes his head morosely. "Well, I don't," he says. "I don't believe in anything that you're doing." For all Mark's doubts and anxieties, he's totally impervious to this kind of abuse when he's working -- this is the moment you realize he's a real artist, even if he's not a great one. He sounds positively gleeful when he describes the setting for "Northwestern," which is also the setting for his own life: "A couple of rusty cars against a rusty background. The earth decays and the cars have decayed and these guys are decaying. That's what it's all about, rust and decay."

Shares