A legendary opera collector owns 817 different recordings of "La Bohhme's" tenor aria, "Che gelida manina." Extreme? Only a little; more than any other opera composed in the past century, "La Bohhme" speaks in the richest fashion to the widest audience.

None of the stereotypes that frequently discourage listeners from attending opera -- corny plots, bombastic drama and music -- apply to Giacomo Puccini's sad masterpiece. It has moved generations of audiences to laughter and tears by telling a simple love story in music of overpowering beauty.

Two poor, young people of Paris -- Rodolfo the would-be poet, and Mimi (the "bohemian girl" of the title), a modest seamstress -- meet and fall in love on Christmas Eve. For the next three acts, the couple struggles to stay together until Mimi's consumption brings their romance to a tragic end. The poetry and drama of this story are so perfectly rendered that "La Bohhme" can be listened to over and over and over again.

When performed by singers in tune with the opera's simple profundity and up to its formidable vocal demands, "La Bohhme" can unite players and audience in the deepest bonds of sorrow and rapture. "Awful!" cries Cher's character in "Moonstruck" after attending a Metropolitan Opera "Bohhme"; "But -- beautiful."

In a legendary Metropolitan Opera performance of the 1980s, Mirella Freni (the most incandescently moving Mimi of the last two generations) sang and lived the title role so thoroughly she had to be helped on and offstage for her curtain calls by her Rodolfo, Luciano Pavarotti; a near-hysterical audience cheered and wept. Even when diluted into an overrated Broadway musical ("Rent" derives from Puccini, among other sources), this tragedy of love vanquished by fate grips audiences with remarkable power.

Every new recording of "La Bohhme" is seized with real interest. The latest "La Bohhme" on double CD was recorded last year in Milan by the orchestra and chorus of La Scala, and is of interest for two reasons.

For one thing, it is the first to employ a new edition of the opera. A study of Puccini's manuscript by scholar Francesco DeGrada, published in 1988, revealed close to 200 details lost somewhere between the world premiere (which La Scala gave in 1896) and the first publication of the score.

In recent years, "corrected" editions of operas have become prolific. Like motion pictures today, opera was a popular art form a century ago. Musical scores were frequently rushed into print to capitalize on the buzz of the opera's premiere, causing many oversights and errors that musicians still unknowingly follow when they perform these works. Sometimes -- as in Verdi's "Don Carlos" (1867) and Alban Berg's "Lulu" (1935) -- entire acts and scenes have been rescued from rediscovered manuscripts or musicians' parts found abandoned in opera house storerooms or libraries.

The corrections to "La Bohhme" are not nearly so drastic, consisting of only a few missing notes and numerous directions for emphasis and expression; a fan will have to listen closely for most of the changes. But by restoring the accents and directions the composer originally intended, performers now have an opportunity to offer listeners a fresher, truer "Bohhme."

That opportunity is taken in this recording, which shouldn't be a surprise because the conductor is the sensitive, conscientious Riccardo Chailly, whose attentiveness to the moment-by-moment onstage action and the needs of his singers is commendable. The Scala orchestra renders the love music with exceptional tenderness (you can practically see the musicians getting high on the score's rapture quotient), and the gigantic second-act panorama of Christmas Eve in Paris is played with real verve.

Chailly doesn't quite let the tragedy of the last two acts hit the listener with full force: Perhaps the new edition of the opera encouraged him to focus on details. But there are times when the sheer emotional breadth of the music should swamp us with emotion -- something that doesn't happen enough in this new recording.

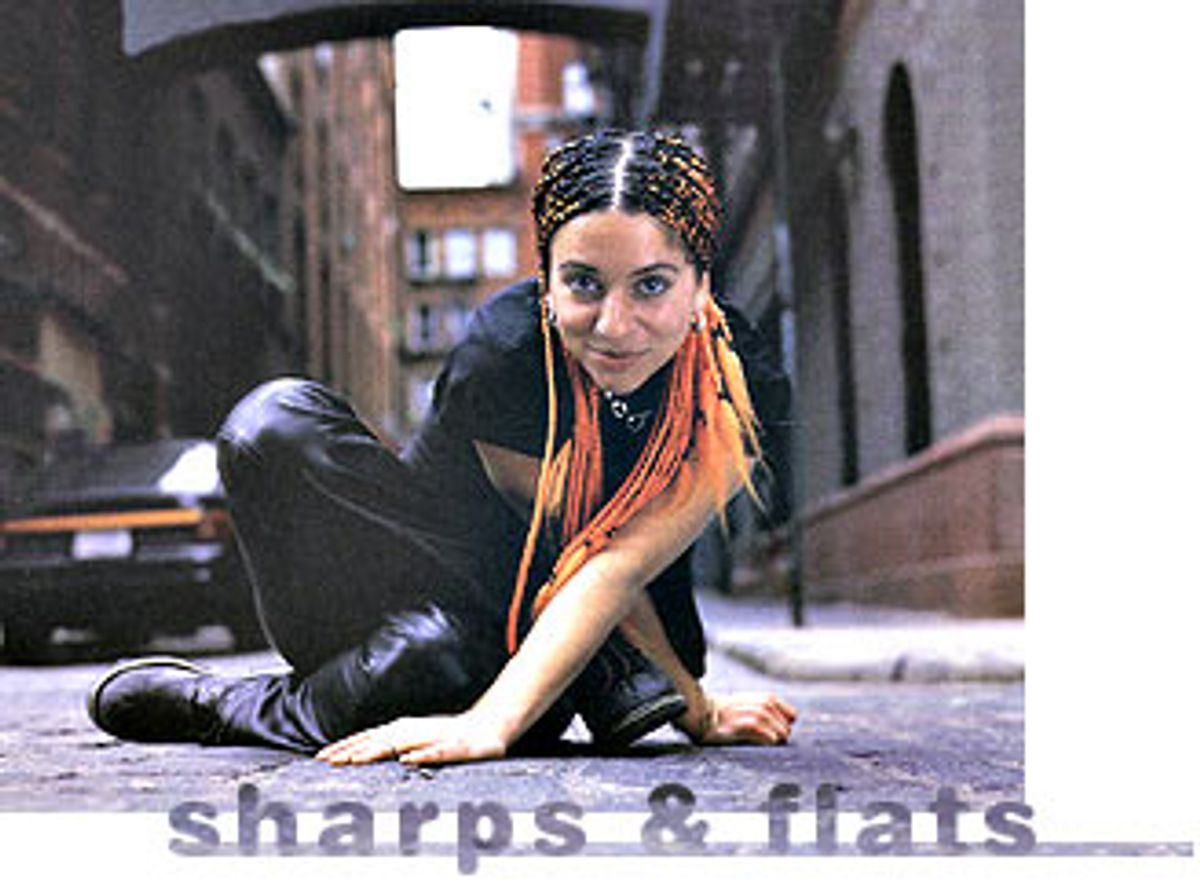

The singers are the second point of interest: They're a "Bohhme" cast close to the characters' ages (late 20s to mid-30s), which adds a livelier air. The fated lovers are played by opera's latest real-life romantic couple, Roberto Alagna and Angela Gheorghiu. (The back page of the libretto depicts the handsome, glamorous duo astride a motorcycle.) Both are sensitive artists capable of bringing details of a score to subtle, moving life. At the same time, both also sound slightly overchallenged by the requirements of their roles.

Rodolfo and Mimi's music shines with lyric sentiment, and in these moments Alagna and Gheorghiu are very good. The desperate but quiet hope in their voices when Mimi and Rodolfo pledge to stay together "until the spring" is the best scene on the album, when the singers become their characters and the listener feels right there with them. But both roles also require voices capable of tough, sustainable power; no matter how starved the Rodolfo and frail the Mimi, when the orchestra soars, their voices must, too -- and higher, so we can hear them.

Alagna's tenor sometimes thins just when the score demands a crowning thrust. Gheorghiu occasionally sounds as if she can weather strenuous phrases only by singing very, very carefully. But they have the allure and sincerity these roles demand, and in the difficult third act raise the action to a convincing level of heartbreak. The rest of the cast delivers the drama well, Ildebrando D'Arcangelo singing the last-act "Coat" aria with firm sound and moving words. (It's one of the strangest arias in opera: To buy medicine for Mimi, one of her artist friends sings an adieu to his winter coat before pawning it.)

Elisabetta Scano's Musetta is the only disappointment: This role demands the sexiest soprano sound available; she should leave the other characters and her listeners drooling. But Scano is never irresistible, with a thin sound and sharp delivery. You can't imagine Parisians scampering around her, enraptured by her charm and beauty. (To be fair, more sopranos have crashed and burned playing Musetta than in almost any other role -- even Maria Callas made a notorious mess of Musetta's famous second-act waltz.)

As in every other art form, each generation remakes opera's classics, reshaping them in performance to their own ends, discovering in the best their own truths and desires. This "Bohhme," less charming and carefree than some heard in the past, rich in emotion but also surprisingly bitter in some of its romance, is very much a Generation X product: Its characters sound like they want so much to believe the old stories of love and beauty are still true, but are afraid at any minute the music will stop and the opera will be over.

Shares