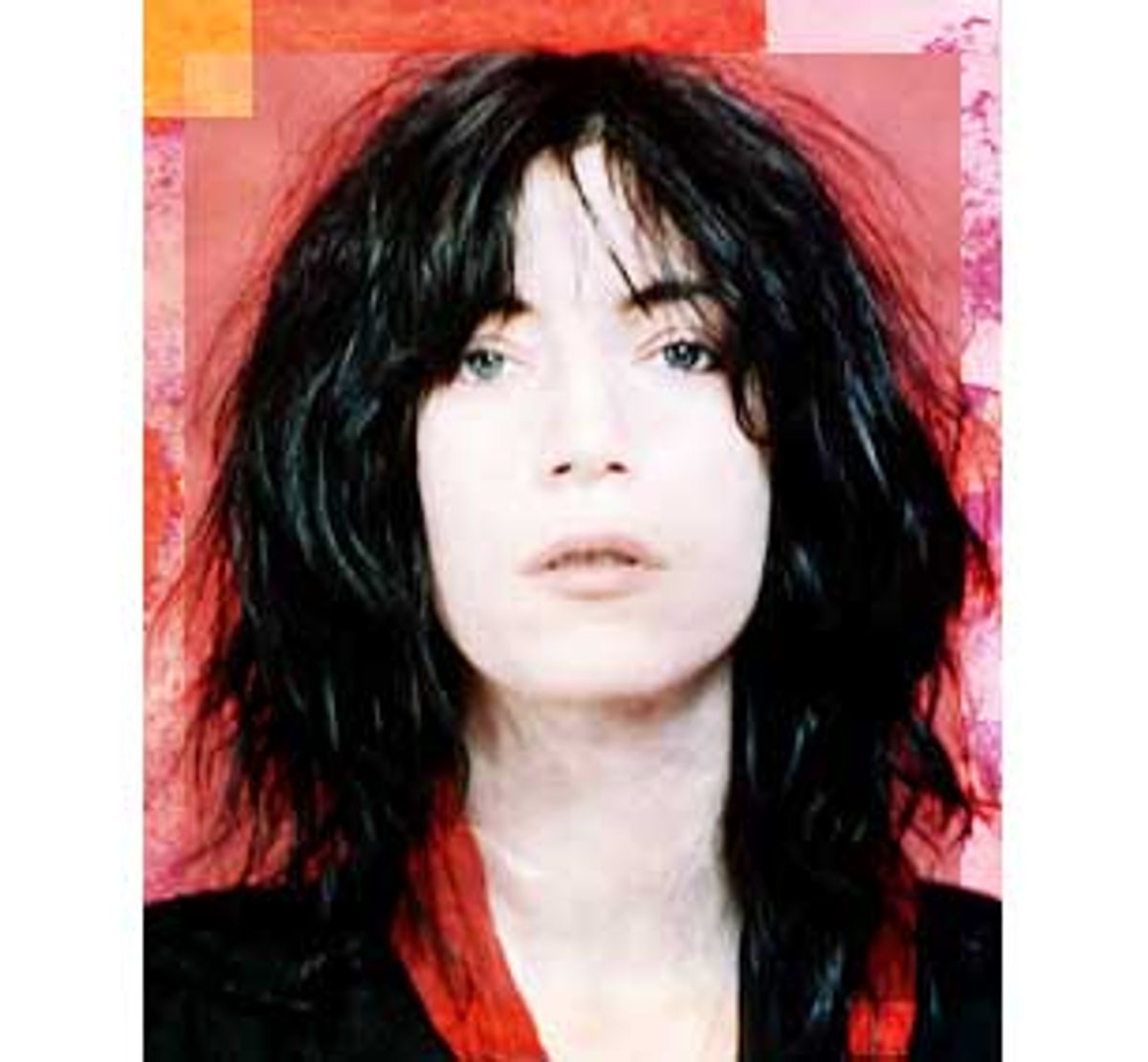

She was a weird icon from the start, a girl who dressed like a boy, a poet

with Keith Richards' hair and a strut copied from Bob Dylan in "Don't Look

Back," a white woman who called herself a nigger, a darling of the

avant-garde who hit the pop charts in 1975 without modifying her vision in

the slightest, then abdicated her stardom when she found better things to

do. Her first album, "Horses," came out nearly a quarter-century ago and is

commonly short-listed as one of the greatest rock albums of all time, but you're unlikely to hear any of it on classic-rock radio: In the mental jukebox

of the populace, Patti Smith is represented, if at all, by her one hit

single, "Because the Night" -- naturally, the most conventional song of all

her '70s output.

When I was in high school in the suburbs, in the early-'80s, Patti Smith was

no kind of icon. Musically, she didn't jibe with buzz-saw punk, ominously danceable

new wave or pasteurized FM radio rock; she evaded the jury-rigged

radar of adolescent rebellion. Teen rebels, of course, generally want an

existing "countercultural" pack to join, complete with wardrobe and hairdo

guidelines. Even if Patti Smith had not recently stopped making records (and

even if we'd known to listen to the ones she had made), she was too much of

a misfit for the misfits to embrace.

In the summer of 1984, I was 18, renting an airless furnished room in the

Rochester ghetto, making less than a living and feeling, in

depressive-undergraduate fashion, alienated from everyone. One

day the eerie silver photo on the cover of Smith's "Radio Ethiopia"

beckoned from a used-record bin -- she's sitting in profile on a tenement

floor, lips parted, and the portrait challenges her own description of

Television's Tom Verlaine as having "the most beautiful neck in rock 'n'

roll." By the time I bought it, she'd already been out of the music

business for five years, but I didn't know that, and it didn't matter. The

album opens with a blast of guitars and Smith's one-word call to arms:

"Move!" It's not an incitement to dance, make out or fight in the streets,

but to emerge, to indulge, to question, to live: "Ask the angels who they're

calling/Go ask the angels if they're calling to thee"; "Everybody wants to

be reeling/And baby baby I'll show you the way." She was unclassifiable, but

she blasted that room open by suggesting all kinds of freedom.

Patti Smith was born in 1946 and grew up in working-class South Jersey. A

bout with scarlet fever at age 7 left her with recurring hallucinations. She

pursued religion for much of her childhood but never caught it -- her

problem was not with God, but with the constrictions imposed by organized

faith. In her teens, she instead embraced Dylan, the Rolling Stones and,

pivotally, the visionary poetry of Arthur Rimbaud. She didn't know yet that

she was going to be a poet, much less a singer.

After a brief stint working in a toy factory, two years in college and a

timeout to have a baby, which she gave up for adoption at birth, she moved

to New York in 1967, with the intention, she later said, of becoming an

artist's mistress. The artist she found was Robert Mapplethorpe, also young,

hungry and determined to make his mark. Following a period of Brooklyn squalor,

during which she drew and painted, Smith spent a few months in Paris, then

moved with Mapplethorpe into hipster central, the Chelsea Hotel.

Though she

and Mapplethorpe soon broke up (his homosexuality was presumably a stumbling

block), they remained close. She began writing poetry, acted in absurdist

theater, collaborated on the play "Cowboy Mouth" with Sam Shepard, became

increasingly well known on the downtown poetry circuit, published books,

wrote swashbuckling rock criticism and, over the course of several years

between 1971 and 1974, gave readings at which she was accompanied by

guitarist Lenny Kaye, eventually adding pianist Richard Sohl and second

guitarist Ivan Kral.

Much of Smith's poetry is in the Jack Kerouac vein of spontaneous bop

ephemera. Her streams of lowercase "babel" tend toward self-indulgence -- on

paper. See her live. In Central Park three years ago, she came onstage late,

apologizing that we'd been waiting for her mom to show up. Patti Smith is a

lot funnier than her records would lead you to believe. She flipped through

her book "Early Work" for a while, but couldn't find the right page. Somebody

shouted out a number. She dutifully looked, then rolled her eyes: "That page

is blank. You trying to tell me something?"

My friends and I were charmed and apprehensive; we weren't there

to listen to poems. She found her page and, while the band waited,

gave a purely electrifying rock 'n' roll performance of "Piss Factory," from

her first single, recorded in 1974. It details with giddy venom her hatred

of the factory grind she experienced at 17. She won't accept this life, she's taking the next train to New York City, she's going to be a big star; her

voice rises steadily in pitch, grows faster, angrier; she concludes

defiantly, "Oh -- watch me now!" (David Bowie had ended "Star," his 1972

statement of purpose, with the same words: The language of ambition is

reductive.)

In early 1975, Smith began playing regularly at CBGB, a biker bar nestled

amid Bowery flophouses. As Legs McNeil and Gillian McCain's scabrously

entertaining oral history of American punk, "Please Kill Me," makes plain,

the punk revolution CBGB hosted had individual precedents in the Velvet

Underground, the MC5 and the Stooges, all of whom had taken distinctly

anticommercial stances and -- surprise -- unequivocally failed to win a mass

audience. Their successors in the protopunk parade, the New York Dolls, had

ascended to downtown notoriety in the early-'70s, but the American market

wasn't ready yet for garage rock in lipstick and platform shoes.

But by

1975, subcultural gravity converged on CBGB, attracted by a small group of

rockers -- notably Television, the Ramones and Smith -- who had little in

common besides a commitment to ignore limitations. Punk was not a single

style, but a boundary-crashing attitude. You could be a punk journalist, a

punk painter, a punk poet. Soon enough, of course, punk would be codified

into a canon of stylistic tics, few of which Smith indulged in, but it's

always worth remembering that the central motivation was to escape limits,

not to invent a new musical cage. As she said once, talking about "Piss

Factory," "What is punk rock, anyway? Is it like, I'm writing something just

to make a bunch of people with weird hair happy? I wrote it because I was

concerned about the common man, and I was trying to remind them they had a

choice."

While she earned her rent as a writer and performer, Patti Smith was always,

before anything, a fan. Her early sets included at least as many covers as

originals, including Smokey Robinson's "The Hunter Gets Captured by the

Game," Lou Reed's "Pale Blue Eyes" and "We're Gonna Have a Real Good Time

Together," the Who's "My Generation" and everybody's "Louie Louie." Though

she borrowed some vocal mannerisms, it was the attitudes and looks of her

readily acknowledged heroes that seduced her as much as their songs -- Dylan's cockiness and mystery; the sinister sensuality of the Stones and Jim

Morrison; everything about Jimi Hendrix.

Smith's models were all male, by

default rather than deliberation. The only solo female rock star to precede

her (as opposed to singer in a male band or packaged pop chanteuse) had been

Janis Joplin, who provided a small example for a writer who, at first, couldn't carry a tune without bruising it. Smith wore loose T-shirts, jeans and a

leather jacket without trying to make a statement of androgyny. She knew

what looked cool, even if no other girl looked that way.

Following in the footsteps of Dylan and Reed, Smith was not the first to

explode preconceptions of what pop lyrics could be. What she added into the

poet-songwriter equation was ecstasy -- not just visceral thrill, the

standard goal of rock, but spiritual epiphany, a striving for communion

with the beyond, which in the abstract sounds like the worst kind of

pretension, but with Smith it was heartfelt. "Horses," the first album to

emerge from the CBGB class of '75, is full of gestures toward

transcendence -- visionary riffs involving everything from love and money

through burning bats and death by drowning; and the music itself, a

swirling, driving assemblage anchored not by garage guitar but by Sohl's

delicate piano.

"Land" contains in nine and a half minutes everything splendid and

perverse about Smith: She whispers, croons, intones and sighs about a boy

named Johnny, who is apparently raped in a locker room; Johnny has a vision

of horses; then we're in the land of a thousand dances, which may or may not

have anything to do with Johnny; Johnny may or may not cut his throat by the

sea. But when Smith belts the party cry "Go Rimbaud!" and gleefully sings,

"And the name of that place is I like it like that, I like it like that,"

she circumvents reason, tapping into that ecstasy by trumpeting the failure of language to express it, as in Sufi poetry.

She works the same trick

throughout the album, in the rollicking "Redondo Beach," "Kimberly" and "Gloria," which achieves its thrill not in its opening kiss-off to Jesus

or because it's a song of lust for a girl, but in the way she holds off for

more than half the song before finally releasing us into the chorus,

breaking the title down into letters, which was the gimmicky hook of Them's

original version, but then playing with the letters -- "I-I-I-I-I-I-I-I" --

until they become pure sound.

The follow-up, 1976's "Radio Ethiopia," is a crunchier, messier work. Smith

played guitar on it, though she didn't actually know how: Welcome to punk

rock. On the other hand, her voice is much surer; she not only hits her

notes, but swoops effortlessly from lilting lullaby to Shangri-la bravado to Buddy Holly hiccup, sometimes in a single line. To

the public and to most critics, it was a comedown from the Top 50 "Horses";

she was castigated for slipping into plain hard rock on the one hand and

impenetrable abstraction on the other. But this is the one Patti Smith album

on which the band sounds like her worthy foil, with enough production bite

behind it to challenge Smith's elastic voice. Again, she bleeds meaning out

of words through repetition -- "wild, wild, wild, wild" over and over in

"Ask the Angels," and "total abandon, total abandon" again and again in

"Pumping (My Heart)." "Poppies" is about drugs, but the clearest indication

that she's not for them is her idiot-junkie imitation, "It was rilly greaat,

maaan." The epigraph on the back, "Beauty will be convulsive or not at all,"

effectively describes the music's occasionally awkward but always warranted

stabs and dives. Cumulatively, even more than "Horses," "Radio Ethiopia" is

a harrowing, ravishing encyclopedia of exaltations, though I'll admit to

unreliable partisanship.

In January 1977, Smith tumbled off a Florida stage while doing her dervish

whirl to "Ain't It Strange": "Don't get dizzy do not fall now," go the

lyrics. She broke two vertebrae in her neck and wound up convalescing for

several months, during which she wrote a book of poetry, "Babel," and

prepared her third album, "Easter." Released in 1978, "Easter" moved Smith

even further toward mainstream rock, though without pandering. The arena

anthems "Till Victory" and "Because the Night" (co-written with Bruce

Springsteen) sonically skirt Jefferson Starship territory, and she was

rewarded with her highest-charting record yet.

Having infiltrated the ears

of mainstream America, Smith pried them open with the hypnotic faux-Plains

Indian chant "Ghost Dance," and "Babelogue," a duet for swaggering poet and

audience that begins at a boastful pitch with "I don't fuck much with

the past, but I fuck plenty with the future," and crescendoes through

glorious nonsense to the finish line: "I have not sold myself to God." In

the searing "Rock 'n' Roll Nigger" and in interviews, she mounted a misguided

campaign to reclaim the word "nigger" for all people "outside of society,"

starting with herself; there were few takers. Politics was never her strong

suit.

Much of the material on "Easter" had been in Smith's repertoire for years,

and the songs that were new seemed more specifically about love and God, as

if she were narrowing the parameters of a personal quest. Around 1978, she

found what she was looking for in the person of Fred "Sonic" Smith, former

guitarist for the MC5. Though she'd had relationships with other intense

artists -- among them Mapplethorpe, Sam Shepard, Tom Verlaine and Allen

Lanier of Blue Oyster Cult, with whom she'd lived for years -- she now

recognized her future, and it was to raise a family with Fred, not expend

her energy on the road and in the studio. The 1979 album "Wave" was a weak

wave goodbye, though with plenty of good moments. "Dancing Barefoot" may be

her best song, and in the stomping "Revenge," she tosses off a couplet that

would have done Muddy Waters proud: "I gave you a wristwatch, baby/You

wouldn't even give me the time of day."

And that was it. She married Fred Smith, moved to the suburbs of Detroit

and had two kids. In 1988, she and Fred released "Dream of Life," which

disappointed fans and was ignored by everybody else, in spite of a great

single, "People Have the Power." Nestled in an over-lush production, the rest

of the songs seemed complacent rather than ecstatic; domestic tranquility

resulted in ho-hum music. She didn't tour, and within a few months it was as

if the album had never happened.

Death brought Patti Smith back. Robert Mapplethorpe died in 1989, pianist

Richard Sohl in 1990. In 1994 came the suicide of Kurt Cobain, one of many

younger rockers to cite Smith as an influence, whose writhings on the hook

of fame she had watched sympathetically. And near the end of that year, the

hearts of Fred "Sonic" Smith and her brother, Todd, gave out within two

months of each other. Strafed by grief, Smith plunged back into music. She

had given a small handful of mostly non-singing performances in the '90s, but

in 1995 she assembled a band again, including old stalwarts Lenny Kaye and

drummer Jay Dee Daugherty, and featuring a young guitarist named Oliver Ray.

"Gone Again," the terrific album she released in

1996, finds her fully in the fray again, grappling with mysteries. "About a

Boy," her elegy for Cobain, is the kind of electric-guitar freakout she hadn't sponsored since "Radio Ethiopia," but much of the album is folksier, in a

Carter Family rather than a Joan Baez way: A slightly sinister fervor

mingles with Smith's determination to survive. In "Beneath the Southern

Cross," though, she allows naked optimism to radiate through sorrow, and the

result is the album's masterpiece and her most affecting song ever.

A year later, in 1997, she released "Peace and Noise," informed by the

deaths of two more friends and mentors, Allen Ginsberg and William S.

Burroughs. It's a dense record, devoid of glee, tough to listen to all the

way through, but every time I do it draws me further in. Smith's voice keeps

getting darker and fuller, and she sounds like a stern angel of judgment on

droning, baleful, minor-key songs with titles like "Death Singing," "Dead

City" and "Last Call" (about the Heaven's Gate suicides). "1959" reflects

her long-standing support for Tibetan Buddhists, and the CD booklet pictures

her and the band in the company of the Dalai Lama. By and large, "Peace and

Noise" sounds more like Christian-period Dylan than like "Horses," which is

to Smith's credit -- she's still capable of changing tack and getting

somewhere new that's worth the trip, which is more than can be said for most

rock performers over 50.

And she's all over the place now. "Patti Smith Complete," a gorgeous

coffee-table book of lyrics, notes and photos, just came out in paperback. A

clumsy, salacious biography by Victor Bockris and Roberta Bayley was

published in September. A new album is due in early 2000. Patti Smith may

have a hard time singing, "I'm so goddamn young" with a straight face

anymore, but she can probably still do a more persuasive "My Generation"

than Roger Daltrey's been able to for the last 20 years. In 1988, she told

an interviewer, "The greatest thing about having done ["Dream of Life"],

besides having had the opportunity to work with Fred, is having created

something that can be inspiring or useful to people in some way. Even if it

just helps them have good dreams." She's accomplished this goal in spades

throughout her career, and before she burns out, sucks up or runs down, she'll do it again.

Shares