I'm obese, and according to the American Medical Association there's a one-in-four chance you are too. Let's find out.

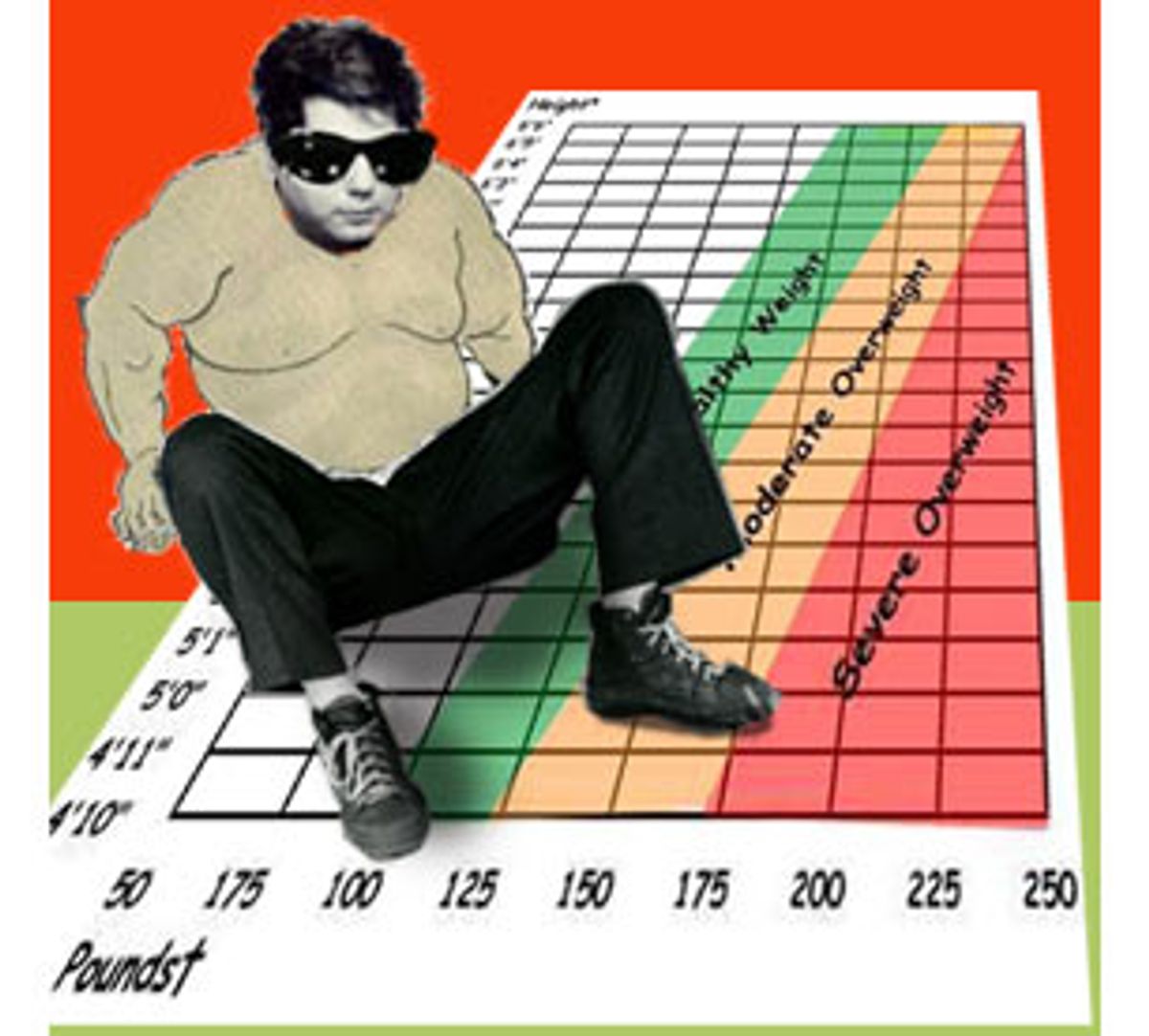

Take your weight in kilograms and divide by the square of your height in meters. Just kidding -- the government maintains a Web site that will perform this computation for you. This is your body mass index, or BMI. If your BMI is between 25 and 30, you're overweight -- that's 42 percent of men and 28 percent of women. If it's 30 or more, you're obese (mine is 35.9; Pavarotti is 42; Princess Di on a good day was probably a 19; the average fashion model is probably an 18), along with 21 percent of men and 27 percent of women.

That's a grand total of 63 percent of men and 55 percent of women who are overweight or obese, according to Aviva Must, Ph.D., of Tufts University School of Medicine in Boston, lead author on the study published in the Oct. 27 Journal of the American Medical Association.

And thus it happened that on Oct. 27 Americans awoke to a barrage of sensationalist TV and newspaper stories triggered by an onslaught of AMA press releases delivering the same old news: Americans are getting fatter.

Rather than finding any joy in this achievement (try complaining to an African about the country where poor people are fat), the AMA struck a shrill, alarmist note. It proclaimed a public-health crisis and dispensed some bizarre, troublesome new recommendations (give fat people painful subcutaneous leptin hormone injections for life) and Dr. Strangelove-esque pleas for social engineering, including a call for "scientifically based interventions that address societal and individual attitudes and behaviors and their environmental context." There was, as well, the same old harmless-but-ineffective advice (eat less; exercise more) we've been hearing for years.

It doesn't take much imagination to predict the reaction to this latest public-health scare: Frightened citizens who still believe everything they read will crash-diet en masse, ultimately gaining more weight than they lose. Concerned mothers will sign up their kids at fat camp (there's a special place in hell reserved for members of the fat-camp industry). And more than a few seemingly normal people will put their dogs, cats, iguanas and flying lemurs on diets.

After reading the press releases, I was first and foremost suspicious of this body mass index thing, and not just because it has an evil ring to it and was invented by a Belgian named Quetlet. Forget those old weight vs. height tables, the BMI people tell us -- this new gender-blind index, based on correlation to mortality statistics, is the measure of the moment.

But how could the measure of ideal weight be the same for men and women? Aren't men supposed to weigh more than women? Puzzled, I sat down with a box of doughnuts and my calculator and set out to deconstruct this statistic.

I dug out the old weight tables that were in widespread use 10 years ago (the good old days, it turns out, for fat guys). The tables divide people into male and female, and into small, medium and large frames. This makes intuitive sense -- more so, to be sure, than dividing your weight by the square of your height. According to the old tables, a large-framed 5-foot 10-inch man can weigh 180 and still be "normal." Yet according to the BMI calculation (which gives us 25.8), he's overweight. For a woman of similar height and frame, the old tables say she's overweight at 174. Yet her BMI of 24.8 keeps her in the normal ballpark. Minor differences, to be sure, but ones that will send armies of neurotic individuals into a collective panic.

So we've been defining obesity down for men, and up for women. That's probably fair, since obesity is so much more upsetting to women than to men, but I wonder about the science. Indeed, when I pressed several scientists off the record, they did eventually come around to admitting that the statistical underpinnings of the BMI indicate differences for men and women.

The medical establishment decided, however, that the value of a uniform rule of thumb was more important than perfect accuracy.

But perhaps the BMI is too generous. Dr. Peter Abel of the Cardiovascular Institute for the South says, "I recall seeing weight tables from the first decades of this century that said a 6-foot man should weigh about 150 pounds. Today it's well over 20 pounds higher, despite the fact that, as a nation, we lead more sedentary lives than our grandparents. That means the additional weight is likely to be fat, not muscle."

Either way, it's probably wise to be very suspicious of any medical diagnosis performed via the Web by a Teletubby-shaped JavaScript calculator with a big heart emblem drawn across its middle. And in the final analysis, measures of ideal weight are pretty meaningless, based as they all are on incomplete data (usually a snapshot of weight on one day of a person's life with no follow-up measurement) and statistical correlations with no underlying reasons (anybody who thinks humans have an a priori affinity for these purportedly ideal weights has obviously never visited an art museum).

Still, it's clear, at least to most members of the medical profession, that being obese is unhealthy. Dr. David Allison of the Obesity Research Center at St. Luke's/Roosevelt Hospital in New York estimates the death toll attributable to obesity at 280,000 annually. Likewise, the diseases correlated with obesity (diabetes, hypertension, coronary artery disease, etc.) are legion, and the AMA predicts that "our health-care system will increasingly be overwhelmed with individuals who require treatment for obesity-related health conditions."

We all know at least one fat guy who has had a heart attack and is now trying to reform. It's a familiar story: The fat guy has the heart attack and then, while lying in the hospital in fear of imminent death, the doctor (who has a too-infrequently indulged flair for the dramatic) appears. The doctor, in full angel-of-death mode, reads the fat guy the riot act: Go on a diet and start exercising ... or die.

So powerful is this image in our culture that, whenever a fat guy has a heart attack, people simply assume it's because he was fat. "He was a heart attack waiting to happen," is what they'll say about me if something else doesn't get me first. But whenever a thin guy has a heart attack (as many thin guys do each day), people are overwhelmed by cognitive dissonance. When my father, thin as a rail and extremely conscientious about nutrition, died at age 58 after a 10-year battle with heart disease, everybody protested, "But he was so thin!"

But self-fulfilling prophecies are not facts; correlation does not prove causation; people are not statistics; and the AMA's obsession with weight has virtually blinded it to other important factors. "Heart disease has a lot more to do with genetics and the lipid profile than with obesity," says Dr. Felix Kolb, an endocrinologist and clinical professor at the University of California Medical School. "People don't like to hear it, but there's a very strong familial incidence of these problems."

In other words, all men are not created equal and life is not fair. That these are the most obvious statements in the world, however, does not deter those who cling to the illusion of control. They refuse to accept that, in many cases, people's genes have sentenced them to early death and that, thin or fat, there's nothing they can do about it. People, Americans in particular, have achieved such a state of hubris that they demand control over death itself.

Even such an independent thinker as Kolb believes that obesity is harmful. But, he reflects, "I just wonder if all these efforts to cure obesity aren't worse."

The AMA is skilled at identifying and publicizing health problems, but the organization's track record with respect to recommended solutions leaves much to be desired. In this case, the AMA's extreme recommendations -- particularly its implicit endorsement of leptin treatment -- cast doubt on the credibility of the medical profession as a whole.

Americans, their doctors included, want a quick fix for every problem -- a pill to make everything go away. I'm typically the last person in the world to defend Europeans, but in this case we have much to learn from them. Despite their goofy clothes and bad taste in music, Europeans at least understand balance, moderation and a healthy, hearty lifestyle. They eat until they're full, drink until they're sated, smoke lots of cigarettes and engage in physical activity only when it's fun (you never see anybody, except an American, going for a run in Paris). Yet they live longer than we do.

The American panacea du jour is leptin. It's a hormone that, while not fully understood, is thought to be involved in regulating body fat by modulating ingestive behavior (leptin is Greek for slender.) In a relatively minor study in New York, 70 fat people (and 53 lean ones, who we can only hope were well paid) were required to give themselves repeated, painful, subcutaneous injections of leptin (or, for some suckers, a placebo).

Some lost weight; others didn't -- and a few gained. Because of the study's weak results, Amgen Inc., the corporate sponsor, chose not to manufacture the drug (although it's now working on a second-generation drug with similar properties). Yet to read the AMA release and the next-day press coverage you'd think the next miracle weight-loss drug was about to hit the market. There's little doubt that the AMA will take a "medicate everybody" approach when a seemingly effective weight-loss drug becomes available. It's as though we learned nothing from the recent Phen-Fen and Redux disasters (to say nothing of the billions of dollars worth of unnecessary and often harmful medical treatment Americans have undergone in the past century).

So, for now, the AMA's only concrete recommendations are the lame old mantras of diet (with a new, and surprisingly reasonable sounding, emphasis on fiber) and exercise. But pretty much everybody, the AMA included, acknowledges that diets don't work. We're talking about failure rates in the 95-percent range. Plus it is well documented that those who fail at dieting often gain to a higher weight. Thus we have the conundrum of obesity: Everybody agrees it's a problem, and nobody knows what to do about it. So our family doctors, taking their cues from the AMA, continue to prescribe diets even though they know it's irresponsible to do so. And, given the known failure rates, it may even be unethical to put a patient on a diet.

Moreover, and perhaps more importantly: I hate people on diets. They're insufferable, self-righteous and invariably cranky. Empowered by the moral imperative of dieting, they believe they are entitled to suspend all rules of etiquette and right conduct. They become bad dinner guests and nightmare restaurant customers, demanding that special meals be prepared for them. They shamelessly comment on other people's eating habits while self-consciously rambling on about their own. And, when they fail, which they all do, they expect everybody to sympathize, forgive and pretend none of it ever happened.

In a way, medically imposed dieting is a form of torture -- the culinary equivalent of sleep deprivation -- and dieters are its victims. I forgive them up to a point, because I know their obnoxiousness is largely non-volitional.

I speak from experience. I must confess I've been on nearly every diet known to humankind (and some known only to me). Back when I still bought into the myth of dieting, I followed Weight Watchers, the Zone, Dr. Atkins and Dr. Dean Ornish (today, the trend is to be a single-issue dieter: Eat carbs; eat protein; eat both, but never at the same meal). I thrilled to the rapid weight loss of the Atkins diet, wherein I ate two pounds of bacon a day, lost 30 pounds in a month, produced the world's stinkiest perspiration and tested my urine with keto sticks. I starved myself on Weight Watchers and went to meetings where I weighed in, got a gold star on my "passport" every time I lost 10 pounds and sat around for an hour a week with a bunch of whiny losers who were begging for excuses and absolution.

Throughout my dieting years, I lost and regained dozens of pounds every few months, and my emotional well-being and disposition hinged on a number on a scale.

And, in the end, I concluded that it's better to be fat and happy than thin and miserable.

Shares