"If God can save an old homosexual like me, he can save anybody."

-- Little Richard

To echo the above words of the Rev. Richard Penniman, if "Dogma" can move an old agnostic like me, it can move anybody. Condemned sight unseen by the Catholic League, nervously dropped by Miramax's parent company, Disney, Kevin Smith's comic-religious fantasy turns out to be the sweetest hot-potato movie imaginable. Alternately sophomoric and serious, "Dogma" is a movie where earnest questions of faith share time with dick and fart jokes, detailed explanation of Catholic doctrine with a sudden exegesis on the oeuvre of John Hughes, where angels and prophets walk the earth alongside gigantic poop monsters.

The sacred and the blasphemous, the otherworldly and the prosaic are inseparable in "Dogma," a picture whose most subversive move may be Kevin Smith's simple and consistent refusal to separate religion from the world that most of us live in. The Almighty's personal messenger tasting (but not swallowing) tequila at the tacky Mexican restaurant down the street? Sure. Angels traveling by Amtrak and Greyhound? Yup. One of Christ's apostles adjourning to a fast-food joint for "a two-piece and a biscuit?" Why not? A good Catholic girl working in an abortion clinic? Absolutely.

The consistent message that has come from the Catholic protests against "Dogma" (just as it did from the Catholic protests against Martin Scorsese's "The Last Temptation of Christ" or Jean-Luc Godard's "Hail Mary") is that it's a sin to question Holy Mother Church. "Dogma" is a comic-book vision of how the church screws itself by wielding such an iron hand. "Dogma" presents a wicked and witty inversion in which Catholic dogma's insistence on God's infallibility creates a scenario that paves the way for the destruction of all creation. And it's only an outcast, someone who has dared the verboten and actually questioned the church, who can save the whole shebang.

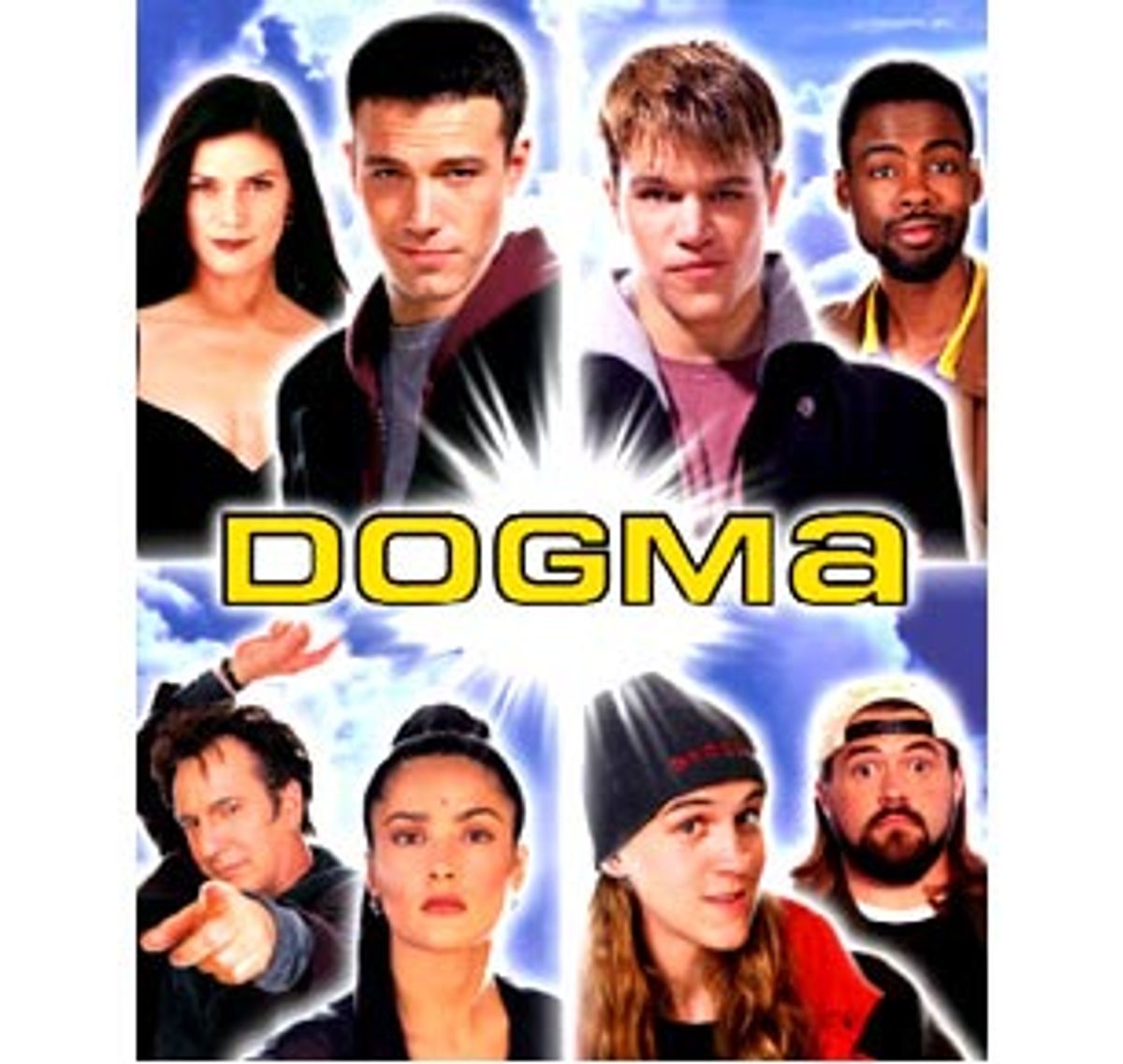

Smith's heroine, Bethany (Linda Fiorentino), isn't so much a lapsed Catholic as an exhausted one. She still goes to mass, but it's long since ceased to mean anything to her. She still prays, but she's long since stopped believing that God is listening. Just the sort of person that God, with what seems like a typically perverse divine sense of humor, elects to save the world. Two angels who have been expelled from Heaven and condemned to spend eternity in Wisconsin -- Loki (Matt Damon), God's former Angel of Death, and his buddy Bartleby (Ben Affleck) -- have discovered a loophole in Catholic doctrine which would allow them to enter the kingdom of heaven, thus proving God wrong and -- whoops! -- negating all existence.

What follows is a topsy-turvy road movie with Bethany heading for Red Bank, N.J., (the angels' ascension will take place at a cathedral there), to fulfill her destiny, picking up various companions along the way. This collection of mortals and divinities are played by an all-star cast who drop nonchalantly into this shambling theological vaudeville to play their rhetorical part. There's Alan Rickman as the Metatron, the fashion-conscious messenger who acts as God's voice, so grand by itself that it destroys mere mortals who hear it. Rickman's presence seems to be a joke on the way Hollywood has always Anglicized God. His exasperated, finicky manner is a joke on the portrayal of the infinite patience of the godly; the Metatron can't believe the slowness of the mortals he has to deal with. There's Chris Rock as Rufus, the 13th apostle, left out of the Bible because it was written by white guys; Salma Hayek as Serendipity, a heavenly muse who takes credit for the 20 top-grossing movies of all time except "Home Alone." ("Somebody sold their soul to Satan to get the grosses up on that piece of shit.")

As a Jersey cardinal who wants to give 'em that new-time religion with his movement "Catholicism Wow!," George Carlin might be playing off the memory of every tough-nosed old-school priest he ever tangled with (and perhaps the memory of an early '60s run-in with Boston's late Cardinal Richard Cushing during his time as a DJ in that city). And there's Smith's recurring duo, the stoner Abbott and Costello, Jay (Jason Mewes) and Silent Bob (Smith, with just two words of dialogue and a beguiling arsenal of facial expressions that gets more laughs than many actors could wring out of a script full of one-liners) as the "prophets" sent to show Bethany the way. They meet her in the parking lot of the abortion clinic where she works because they figured it'd be a good place to pick up loose women. As the characters argue and debate, eat, get drunk and argue some more, "Dogma" blends the bleariness of a road trip with the bleariness of an all-night bull session.

It's inevitable that when any work is condemned as sacrilegious, critics rush to its defense, claiming that the accusers have gotten it wrong, that the work in question actually venerates the very concepts it has been painted as defaming. But that defense only raises the question, would something that's truly blasphemous not be worth defending? Every critic who's stepped up to the plate to defend "Dogma" has been quick to point out what a reverent movie it is, and they're not wrong. This is a movie that absolutely believes in God's love and forgiveness, and that has faith in the ability of people to distinguish that love from the hateful and just plain ignorant things that are done in God's name. Presumably, that's what led the New Yorker's Anthony Lane, in his now perfected tone of amused condescension, to dismiss "Dogma" as the jape of a "suburban absurdist, not a satirist" and therefore nothing to get excited over. (What would excite Anthony Lane, I wonder? Hot needles jammed under his fingernails, perhaps?)

But "Dogma" wouldn't be as moving as it finally is if Smith didn't still feel a passionate connection to Catholicism. The thrill of the movie -- and the reason you don't have to be religious to be caught up in it -- is the thrill of watching a director wrestle with his obsessions. For all their (mostly verbal) outrageousness, Smith's comedies have always been remarkably sweet-tempered. And therein lies the real shock of "Dogma." The critics who have focused on Smith's reverence or, like Lane, continue to see him as merely a jokester, have completely missed the undercurrent of bloodlust that's loose in "Dogma." Yes, the movie is about how you manage to hold on to faith, but it's also about rage as a natural component of belief. For the characters in "Dogma," being a believer means being in a near constant state of rage over what God has had the audacity to ask them to bear. For Bethany, it's the gall of putting the responsibility for the world on her shoulders but not doing anything to change the fact that she's unable to have a child. (Fiorentino has something like a pliancy here that, given her usual unvarying Lauren Bacall schtick, I would have her sworn her incapable of.) And there's a bitter yet tender scene in which the Metatron asks her if she can imagine what it was like to have to explain to a 12-year-old Jesus what fate God had in store for him.

The movie's rage really breaks loose in the scenes with Damon and Affleck as Loki and Bartleby. Figuring that he and Bartleby are headed back to heaven with all transgressions forgiven, Loki takes up his old job as the Angel of Death, slaughtering any commandment breaker he runs across. The tone of these sequences are often a little off, even a touch unpleasant, and yet "Dogma" benefits from the way they throw the picture off-balance. Without the chaos sown by Smith's avenging angels, the movie might seem a bit benign. But the carnage gives Smith a chance to plunge right into the bloody obsessiveness at the heart of Catholicism (the way those shots in "The Last Temptation of Christ" of the angel of the Lord pulling the nails from Christ's feet and kissing his bloody wounds gave Scorsese the same opportunity).

The casting of Matt Damon and Ben Affleck are crucial to these scenes. Already there's a temptation to see that casting as a chance for the actors to do their buddy-buddy routine. But Smith wants to lull the audience into enjoying their reunion and then put the whammy on us. The context is everything. Seeing the naughty-boy gleam in Matt Damon's eye after he's dispatched some sinner, the laughter sticks in you throat, because we've become the butt of the joke. He has the cold, turn-on-a-dime mood swings of a psychotic put-on artist. He and Affleck jump into the roles without a thought of being likable. There's a hardness to their performances, a willingness to screw with the audience's heads that gives the movie a flinty edge.

At the New York Film Festival press conference for "Dogma" Smith said that he considers himself less a director than a writer, and in a way he's right. Relying for his meanings almost entirely on words, Smith doesn't care about visual style, and his staging is often flat (particularly in the scenes with Jason Lee's Azrael). He has no instincts for large-scale action. And so in the Armageddon showdown that climaxes the film, a sequence that desperately needs that instinct, Smith can't really find the right tone for it and the action just seems busy.

And yet there's something about the tonal confusion of the sequence that keeps it from becoming pat. There are all kinds of ways in which it could be better, but Smith doesn't stint on any of the emotions it provokes -- the laughs, the horror, or, in the final moments, the exhilaration. When the angels spread their wings you're aware of the special-effects guys working to make it look good, but the cheesiness has the zap of a great comic book panel come to life. And the violence carries a jolt because we weren't expecting the movie to go as far as it does. It's as if someone has slipped a print of Luca Signorelli's "The Damned Cast into Hell" into a copy of "The Mighty Thor."

Perhaps Smith's reliance on his dialogue is the reason he takes such care with his casting, and why he gives "Dogma" the perfect capper in the oddball triumph of Alanis Morissette as God. Alternately stern, forgiving and a goofball, Morissette comes very close to the comic sublime here, whether she's cradling a fallen angel in her arms or dropping down on her haunches to smell some flowers, very pleased with her own handiwork. There's no more perfect emblem of the movie's blend of the silly and the serious than seeing Morissette's God go from dishing out divine fury and benediction in her Christian Lacroix outfit, to watching her do a handstand and reveal a pair of baggy plaid boxers.

It would be the easiest thing in the world to dismiss "Dogma" because it's so formally messy, but that strikes me as a particularly bloodless response to a movie that makes up for its lack of technique by its director's urgent involvement with his subject. This is perhaps a comedy of ideas, certainly a comedy of passionate argument. And the key to it is Smith's treating religion as more familiar than sacred, something so much a part of his life he can joke about it and pick at it, zero in on its flaws and quirks and keep scoring bullseyes.

There is one absolute sin in "Dogma," spelled out by Salma Hayek's Serendipity: treating God as a burden rather than a blessing. "You people don't celebrate your faith," she tells Bethany, "you mourn it." Smith is determined not to make that mistake. It's fitting that, in the film's finale, God's blessings take place not in the church but outside it. What's the point of revering the Creator, Smith is asking, if you treat the creation as a shade? Celebration, Smith concludes and the humorless zealots attacking him confirm, is too important to be left in the hands of organized religion.

Shares