Last month, Wayne Newton signed the "most lucrative" contract of his quixotic career, a 10-year, 40-week-per-annum mega-deal with the Stardust Casino in Las Vegas. He won't discuss the terms of his contract, but about 1,000 miles east of Vegas, Newton is thick in the middle of another potentially lucrative blockbuster to which the financial terms are public information.

Newton filed a $20 million lawsuit against fellow croonmeister Tony Orlando. Actually, Newton's June 21 suit was a return volley -- Orlando fired the first salvo in this real-life Celebrity Death Match, having launched his $15 million lawsuit against Newton two months earlier, on April 28. Their feud centers around the theater that -- up until December --

Newton and Orlando shared in Branson, Mo.

Branson is, without question, the preeminent Ozark Mountain vacation spot. Replete with more than three dozen musical revues, paddle-wheel riverboat cruises and a 19th century theme park, it's also home to a boatload of once-famous entertainers -- from Andy Williams to Yakov Smirnoff -- whose careers have gotten a third wind in this show-biz anomaly in the southwest corner of the "Show-Me State."

But venture just a little bit outside of town -- say 10 minutes south down Highway 65 -- and suddenly you're not in the "Las Vegas of the Midwest" anymore. There, in rural Arkansas, sandwiched between the Omaha Church of Christ and what's left of the dilapidated Dinosaur Dumplin' Palace, you'll find Bax's Guns of the Ozarks, a scary bumpkin bazaar whose sign advertises an "AMMO SALE 62 3.75 BOX," whatever that means.

There's just no escaping the fact that Branson, which wags have dubbed "the Redneck Riviera," lies perilously close to genuine Hatfield and McCoy country, where feudin' fever is as common as 'possom pie. How else to explain why two performing pals -- who had been friends for more than 30 years -- would now be embroiled in a particularly ugly celebrity squabble?

Yellow ribbons and red roses

In case you snoozed through the '70s, here's a little refresher course to help you tell one cheesy entertainer from the other. With his band Dawn, Orlando recorded three No. 1 tunes: "Tie A Yellow Ribbon Round the Ole Oak Tree," "Knock Three Times" and "He Don't Love You (Like I Love You)." The trio even enjoyed a television variety show on CBS for two years in the 1970s.

Newton never reached No. 1 on the pop charts, though his repertoire, which includes "Danke Schoen" and "Red Roses for a Blue Lady," may be familiar. Still, by maintaining a maniacal appearance schedule -- mostly in Las Vegas -- Newton is said to have become the highest-paid nightclub performer in history.

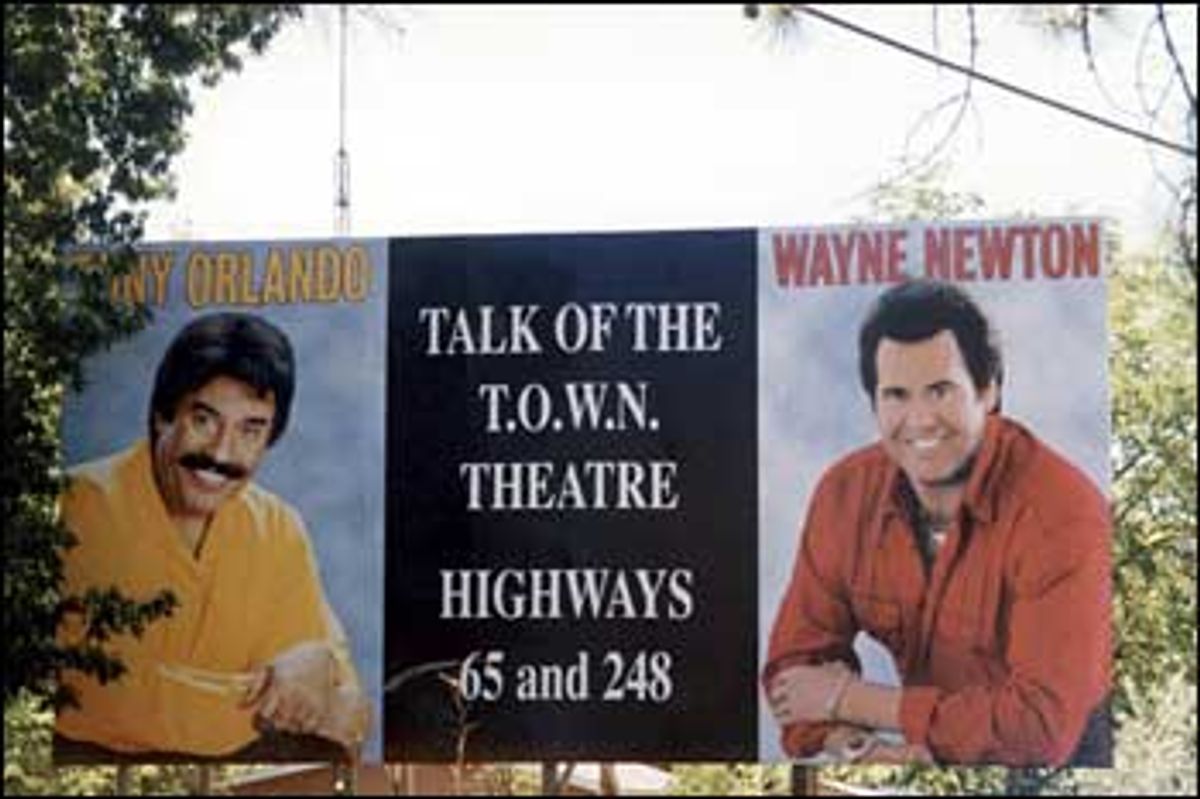

Though they took slightly different paths to fame, Orlando and Newton mined the same sort of fun, schmaltzy material, and the two former friends shared so much more. They both dropped their first names -- Carson Wayne Newton had a professional "Carson"-echtomy, while Michael Anthony Orlando Cassavitis disposed of both his first and last names. In 1997, Orlando invited Newton to share the stage with him at Tony's Yellow Ribbon Theatre in Branson. And in April 1998, they even leased a theater together, which they christened "The Talk of the T.O.W.N. Theatre," an acronym for "Tony Orlando Wayne Newton." Sadly, all they share today is their April 3 birthday. Oh, and a mutual hatred for each other.

That's because their theater on Highway 65 at the junction of Highway 248, though still very much the talk of the town, has changed its name to the "Wayne Newton Theatre." And it was here that, almost a year ago, Newton and his wife locked Orlando out in the December cold.

What could possibly have transpired to put good friends at odds with each other? To engage in a juicy "He said, He said" war of words in which accusations of illegal wiretapping, conspiracy, planting of evidence and the kidnapping of a young girl's Christmas toys have played a part? To stage a battle royale in a Springfield, Mo., federal court where even the "Omnibus Crime and Safe Streets Act" has made a cameo?

Tony's tale

In Orlando's version of events, Tony heard that Wayne was considering leaving Branson because, according to Rob Wilcox, Orlando's publicist, Newton had been involved in disputes with two other theater owners. Tony took Wayne under his Branson wing and got him a gig at the venue where he himself was performing, the Yellow Ribbon Theatre. When Tony's lease at the Yellow Ribbon was up, he

fielded numerous offers from suitor venues, including the Glen Campbell Theatre. But Tony heroically made it clear that he would only come on board if his buddy Wayne was included in the deal. The Campbell people went for it, and the theater was renamed the Talk of the T.O.W.N.

According to court documents, it was agreed that White Eagle Inc., a theater management group and holding company whose sole shareholder is Kathleen McCrone Newton (Wayne's lawyer

wife), would be the contractual lessee and run the business side of things.

But it seems as if Kathleen Newton was the Yoko Ono in this supergroup: She denied Tony access to expense accounts, raised the costs of his contributions to the joint "kitty" account and bullied him in attempts to get him to renegotiate the contract.

Things were starting to get ugly when Newton scheduled a powwow. On Dec. 9, 1998, Newton's people met with Orlando and his people in

Newton's dressing room -- Wayne himself had left the theater hours earlier. Orlando alleges in

his suit that he got wind that something was amiss and went on to discover that Newton was secretly taping the meeting. A search of Newton's dressing room, Orlando claims, revealed a tape recorder in a house plant.

Days later, the Newtons locked Orlando out of the theater and canceled his 11 remaining Christmas shows. In April 1999, one year after the curtains went up in the Talk of the T.O.W.N. Theatre, Orlando slapped Newton with a $15 million, 11-count lawsuit. While citing the Newtons' "evil motive," the suit's counts included "a violation of the anti-wire-tap statute" in the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act and a "civil conspiracy" to surreptitiously tape record Orlando and lock him out of the theater, "so that Wayne Newton would be able to rename the theater as the Wayne Newton Theater ... and to enable Wayne Newton to have the theater to himself."

How "Macbeth" is that? Tony "Duncan" Orlando rewards Wayne "Macbeth" Newton with a nice gig as the thane of Branson, when suddenly Kathleen "Lady Macbeth" Newton gets into the act, shouts, "Out, damned spotlight," and encourages her husband to completely usurp Orlando's power, claiming the kingdom as his own.

Intermission

(Featuring the music of Chuck Mangione.)

And now back to the story.

Wayne's way

Newton's side of the story is no less entertaining. In this account, Tony "Wimpy" Orlando will gladly pay White Eagle Tuesday for a share of the theater today. But many Tuesdays come and go and Orlando never does live up to his financial end of the bargain. First Newton says that Orlando's "failure to pay his pro rata share of the expenses of White Eagle, Inc., generated from his shows and his share of the overhead in accordance with the Agreement was seriously straining the business relationship."

Even worse, according to Newton's suit, Tony was not exactly a stellar attraction. White Eagle was having trouble making ends meet due, "in substantial part, to Tony Orlando's inability to draw even 50 percent of the 750 person per show attendance figure he had represented he would draw." White Eagle also claimed that Orlando had suckered them into the agreement with false information as to his drawing power.

(Ron Stenger, the former owner of the Yellow Ribbon Theatre, confirmed that, when Orlando was headlining the Yellow Ribbon, "the draw was less than satisfactory" and that for the length of its four-year run, the theater was a "money-losing operation.")

Oh, and as for Tony's version of how he and Wayne got together in the first place? Wrong. In Newton's account, it was he who was approached by the Glen Campbell people. The "principals wanted Wayne Newton as their headline performer, but if Wayne Newton agreed to certain provisions and other agreements could be reached, they would consider having Tony Orlando also perform at the theater."

As for the taping scandal, Newton claims that it was Orlando who was playing Tricky Dick, not him. For some reason, Newton's suit claims, the meeting that took place in his dressing room between Orlando and Newton's agents was picked up by sound equipment onstage at Tony's monitor board. Orlando instructed one of his henchmen to start recording the proceedings, unbeknownst to the other participants. At the intermission of Orlando's show (the show must go on!), Orlando returned to Newton's dressing room and told Newton's rep that there was a wireless microphone in the room. A search of Newton's dressing room ensued and -- voil`! -- a bug was found hidden in a house plant.

Ah, but there is an explanation for that, you see. That wireless mike had been placed in Newton's dressing room "routinely ... in an effort to determine the person or persons responsible for numerous thefts and vandalisms which had occurred in Wayne Newton's dressing room involving professional and personal property of the Newton family."

In his $20 million countersuit, Newton characterized Orlando's actions as "willful, wanton, and malicious." Such charges stem in part from claims that Orlando and his publicist knowingly disseminated false statements to the media, including the gem that "Newton refused to allow Tony Orlando to remove personal and professional items [from the theater], including holding his daughter's Christmas toys hostage."

Darn the torpedoes

So what do poor Bransonites do when these big-time show-biz movers and shakers come to town and start litigating? "No one really understands what happened," Dori Allen, public relations manager of the Branson/Lakes Area Chamber of Commerce and Convention Visitors Bureau, said. "We all just went, 'Darn.' We knew there was some kind of tiff. This is something that would not happen in our everyday lives, but it would be great if they

could work this out."

Listening to their respective corners, that doesn't seem likely too soon. "Tony had a very difficult time realizing that someone he thought was a friend didn't have the same good intentions that Tony had in his heart," Wilcox said. "But now he's doing incredibly well. For the millennium, he will be headlining the Taj Mahal in Atlantic City. All of the spinning that the Newton side has been trying to do isn't going to hold water."

Newton's lawyers sent me a formal "Response to Tony Orlando's Publicist's Remarks":

With Tony Orlando's obsessive desire for publicity on this story, or lack thereof, it has become apparent that Tony Orlando has chosen to ignore the distinction between what is truth and what is fiction. He is a poster boy for the old adage "if one tells a falsehood long enough and to enough people, that alone makes it true." Tony's one-sided story is just that, a story, a fictional story. Mr. Newton has no problem sleeping at night and spends his entire day not thinking about Tony Orlando or his attempt at writing fiction.

The last week in October, Newton inked the deal with the Stardust Resort and Casino. Forty weeks of every year he will headline the hotel's newly named performance space, called -- wait for it -- the Wayne Newton Theatre. His lawyers say he will also honor his Branson contract, which runs through 2001.

"Mr. Newton still does have obligations in Branson," said a

spokesperson, "which he will absolutely fulfill because he is a man of his word."

I asked one of Newton's lawyers if this new deal would patch things up between the boys and bring Orlando back into the Wayne Newton Theatre.

"Turning it back over to Tony implies that Tony had it in the first place," said a Newton lawyer. "Tony playing again at that theater is not an option that I know of at all. I have not heard that one discussed."

So, for us everyday citizens, we can only hope that Tony hears a knock, three times, on his ceiling. Perhaps then, he'll know that Wayne wants him.

But he shouldn't hold his breath.

Shares