I often write about violent people, and the way I write about them usually makes people mad. People tell me my work makes them queasy because I obviously spend a lot of time with homophobes, killers and rapists -- and a lot of time thinking about them and writing about them. Weirdest of all, I apparently feel concern for these creepy people, even though I'm the kind of person they target.

Someone once said all Southern literature is about either admitting or denying one's "whippedness," and the same thing definitely applies to my writing. A member of several oppressed groups (gay, Jewish, female, more below), I have always related strangely to all threatening people and things: violence, hatred, terror, the site of our undoing. The place we were originally hurt, and where we may well be hurt again. Loss. Enemies. What can never be repaired or restored. The dark place. The place that preys on us, years after we've left it behind. I have always wanted to go there.

Am I brave, or just a masochist? I've always wondered.

I once spent a week with the Rev. Fred Phelps, the man who beat all his kids and cheers when gay people die, and I ate Hostess cakes served by his wife. I went to the terrible hog farm where Brandon Teena was raped and I registered in my mind's eye the brutality of what she was put through, kicked over and over in the mud with the smell of pig shit everywhere. I spent three days at a Christian Coalition convention, and I clapped for Beverly LaHaye till my hands hurt while wearing an absurd pink dress so I would know what it felt like to be a woman who was a misogynist. I reported on a man killed by New York state prison guards in a unit where the guards are so violent they alter Beetle Bailey cartoons on their bulletin board so that the punch lines are about beating prisoners. I spent several years going to religious-right meetings so I could understand what made people antigay and punitive, but sometimes ecstatic and kind, too.

At the moment, I'm researching a long article about what motivates cops to humiliate and attack people. I recently wrote about the complicated feelings about sex that I could guess had motivated Matthew Shepard's killers, because I have often had similar feelings, even though I'm no murderer. Once I even wrote a country song narrated by Jeffrey Dahmer.

Someday, I want to write about the loneliness of batterers, and the sad and unfulfillable yearnings of sexual abusers.

Where does this endless catalogue of rogues come from? Why would I ever want to write about their moroseness and difficulties, their pain and their occasional goodness? Why can't I stop talking about them?

I want to tell you why I need to go into that dark cave and talk to the people that I find there. It makes some people nervous. Some people would prefer that I not go in, or that I be a little more blind when I do go in.

Part of the reason that I write about hurtful people is chosen, and part of it is basically unwilled and uncontrollable. It's sort of like being gay. My orientation has been to write about hurtful people -- although I believe that all orientations are fluid and that they often involve choice. In fact, my orientation as a writer may eventually change. But my orientation has also always been to attempt to turn the dross in my life into gold -- and writing is one of the best ways to do that.

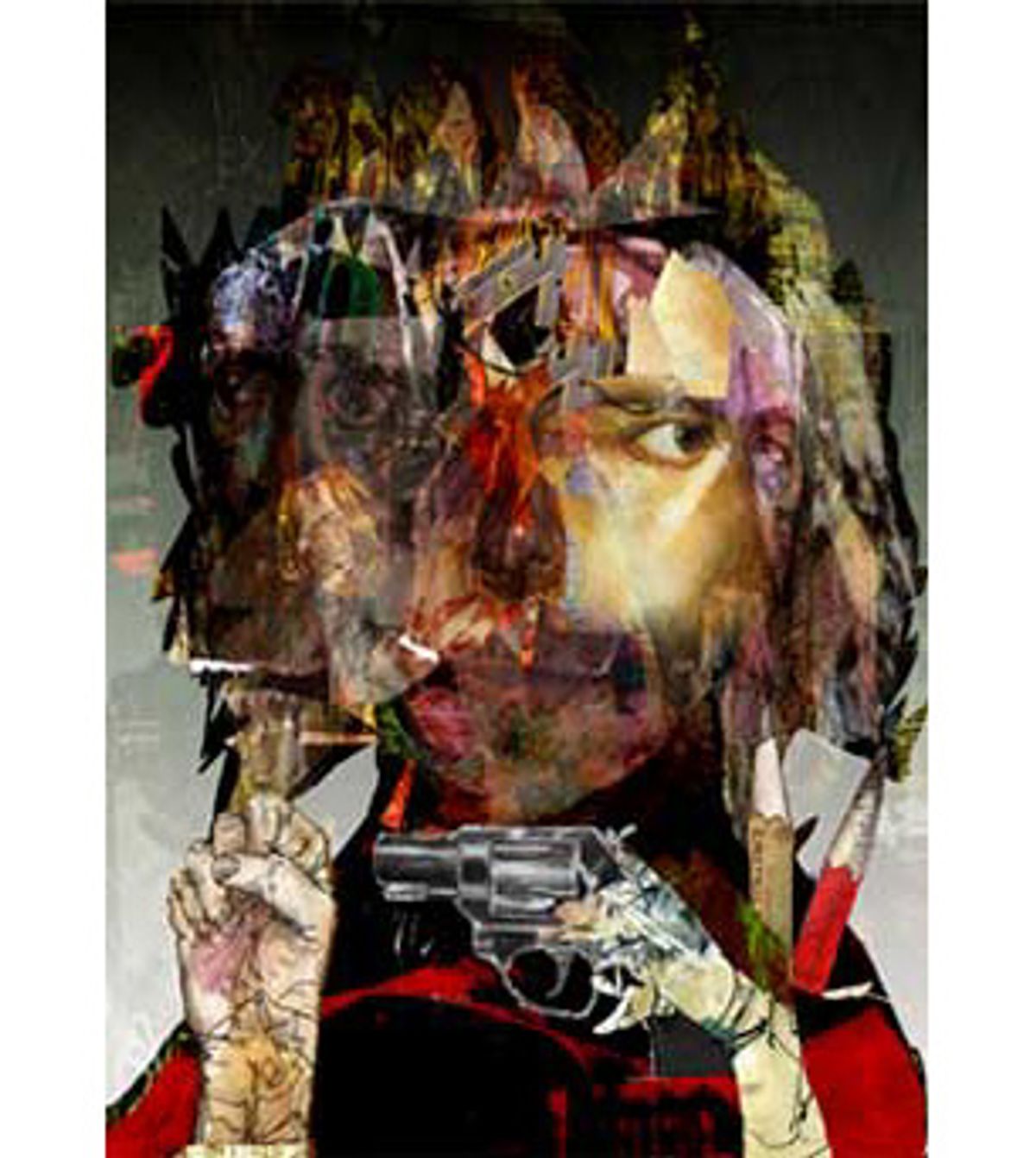

It's an odd sort of project, changing fear and violence into gold -- or let's say, into beauty -- by writing about them. In some ways, it's deeply grandiose. In some ways, it is based on the impossible assumption that I can endure anything, encounter anything, go anywhere. Make anything over into something useful and good.

It's not surprising that in my writing and my life, it has sometimes been hard for me to tell the difference between masochism and bravery. Not only do I feel compelled to make bad things good, I feel compelled to do some of the hardest things there are. And, especially in my writing, I make myself do hard things to a degree that occasionally scares me because I can't say for sure if it's completely my choice or just the darkness calling to me, trying to be made right. Something in me continually calls on myself to prove my courage and endurance, to stand up to the hard thing and to watch myself standing up to it.

And I'm compelled to risk angering people -- in my writing, if not in life -- in the same visceral and not-quite willed way. My provocativeness, my ambiguous, masochistic courage, is both the trait of mine I'm fondest of and the relic of one of the worst experiences in my life -- my father's violence. It is a strange gift I get from violence that lets me go to places people who have never been assailed are often unable to go.

Obviously, there are reasons to be suspicious of gifts like this. Traumatized people often take risks that are not worth it, risks that are only reenactments of an original danger we have somehow fallen in love with. These are risks we take without knowing why, risks we can't help taking, because part of us senses that they might be a way to become healthy, a way to finally master the evil thing. But such unknowing, uncomprehended risks often bring us nothing but a brief rush, and sometimes leave us even more vulnerable than we were to begin with.

My need to write about haters and violent people is, on one level, just such an unconscious reenactment. But thankfully, that's not all it is. Writing is one of the safest venues I know for taking risks, and one of its glories is that it can be done supremely consciously. It is also genuinely a way you can encounter anything, endure anything, go anywhere.

Whitman said, "I play not a march for victors only ... I play great marches for conquered and slain persons ... Agonies are one of my changes of garments. I am the hounded slave ... I wince at the bite of the dogs, /Hell and despair are upon me ... crack and again crack the marksmen, I clutch at the rails of the fence ... I am the mashed fireman with breastbone broken ... tumbling walls buried me in their debris ..."

Adrienne Rich wrote, "I came to explore the wreck./ The words are purposes./ The words are maps./ I came to see the damage that was done/ and the treasures that prevail./ I stroke the beam of my lamp/ slowly along the flank/ of something more permanent/ than fish or weed ..." Rich looked for "the evidence of damage/ worn by salt and sway into this threadbare beauty"; Whitman famously became the man bleeding to death, the prisoner, Christ on the cross himself.

You might ask what this has to do with my own pieces that identify with Aaron McKinney or say what it is I have in common with Fred Phelps. The answer is, everything. It is a happy fact that it is impossible to engage in this sort of fearlessly empathetic writing without being willing to share the identity and pains of everyone and everything, if only for a moment and if only in a poem. Empathy is precisely about not shutting off, not rendering anyone outside the category of the human; empathetic writing is precisely about making the most disturbing, painful and frightening traits, people and things acceptable, knowable, identifiable with.

When I use the word acceptable in such a context, I'm sure it pushes some people's buttons. I don't mean condonable or defensible, I don't mean acceptable in a moral way. I mean something far more basic and important: something on the order of un-exileable. Unestrangeable. Ultimately inseparable from the rest of us.

The alarming fact is that all of us have more in common with Aaron McKinney than we have that separates us. All of us are potentially murderers and bigots. All of us have wanted to strangle what we find threatening.

What we do with that fact is the greatest moral task facing us. In fact, the basic reason to write about the violent in an empathetic way is so as not to become them. Becoming them is what I have always been most afraid of and what I will always, wisely or foolishly, work hardest to ward off. Becoming my father has always been the worst thing in the world to me -- worse even than being hit by my father. Truly, I don't want to be either. But while I can't absolutely control whether or not I'll become a victim again, I do have absolute control over whether or not I'll be an abuser.

And the only way to not be one is to see very clearly how I could be one.

Rich and Whitman's empathetic writing about slaves, victims and prisoners has everything to do with empathetic writing about abusers, and it is no accident that they both do both. "Every Harlot was a Virgin once," wrote Blake. Every abuser was a victim once. Every act of abuse is a response to an original perpetration, or to several. Abusers and victims intermingle across the ages and become each other, to a degree that most of the abused never want to see. Abuse has always been the original temptation waiting for every victim, the true nightmare waiting for us.

I don't believe in God, but there but for the grace of God go I. I have had to choose empathy because empathy is the only thing that is truly an opposite to violence. Someone famous once said, "If you love only those who love you, what reward can you expect? Surely the tax-gatherers do as much as that. And if you greet only your brothers, what is extraordinary about that? Even the heathen do as much. There must be no limit to your goodness, as your heavenly father's goodness knows no bounds."

I'm not a Christian, and I'm sure I'll never become one. But the extraordinary thing about what the mythical Christ is supposed to have done is to have become one with everyone, including the lowest, including criminals of every stripe. Tax-gatherers in his day were people who assaulted the poor to get money for the Roman Empire. But he ate with them, and he identified with all wrongdoers and prisoners, and if he were alive today he would seek some protection for Aaron McKinney and take that lost, self-hating 20-year-old in his arms. "What you do to the least of these," he said, "you do to me." Meaning: Punishing him is as bad as punishing me. Subjecting him to violence -- as he will indeed be subjected to in jail -- is as bad as subjecting me to violence. It is the site where abuse is born.

Those who, like me, have campaigned to put certain terrible people in jail need to think long and hard about our responsibility for prisons and the constant violence, rape and degradation committed there in our names and with our tax dollars and our moral authority. We will be judged not by how we treat the best people, but how we treat the worst ones, the ones it is easy to hate, the ones it is easy to think of as a kind of human garbage.

So one reason I have done the kind of writing I do is as a kind of spiritual practice. But I have done it for a number of great, selfish reasons too. One is that by looking at the humiliated, empty lives of the violent, I can see the great lie of our culture for the fiction it is: Violence isn't strength. Everything, even my favorite TV show, "Buffy the Vampire Slayer," encourages us to think that violence leads to happiness, that the abusive have a grand old time socking people, raping strangers, stirring up hate and terrorizing their loved ones.

My experience and the research I've done for my stories tells me this is not the case. I am very glad I am not so estranged from sex as to be able to take pleasure in having sex with someone who doesn't want to have sex with me. I thank God every day that I am not a batterer, someone who can have no real love in her life, and no uncontrolled relationship. Most things of worth in our lives depend on vulnerability and trust, and I am delighted to have learned through my work that, in effect, the violent cannot win. They cannot win because the things that violence gives you -- a very temporary respite from your own feelings of helplessness, and the experience of others' fear and submission -- are not anything worth having.

Because I am a writer and my business is to speak the truth and to reconcile with it, I'll be honest with you here: Part of me wishes I could be violent. Part of me thinks that yes, it would make me happy to crack my fist across somebody's face, and that violence would get me everything I want. I would never know another moment of helplessness, rejection or sorrow. I would force everyone to do what I want and I would have everything I want, always!

It's a myth. The thinking part of me knows it is not true because it depends on controlling the world and something, somewhere would always resist my control. In fact, the violent are as enslaved as the abused because they live in fear of the world going out of control, not obeying them. It is ridiculously easy for them to feel as helpless as their weakest victim.

Which brings me back to empathetic writing and what I get out of it. I've just put a very frightening thing in words, my longing to be violent. Now I will put another frightening thing in words: I'm very, very frightened of my capacity to be a victim. Probably one of the reasons that I write the way I do is that I much prefer to see myself as a potential abuser than as the actual, historical victim that I am. It is terrible to see myself as a victim, to continue looking while I see my great pain and helplessness, my subjection and my shame. The entire culture hates victims and blames them, and I have certainly absorbed some of that hatred and self-blame.

I obsess most days about whether someone has taken advantage of me, whether I've failed to stand up for myself, whether I have somehow colluded with the people who want to hurt me. The idea that I might somewhere in some part of me desire to be a victim is constantly there like a vulture at my internal organs, and is probably the worst legacy that I get from my father. These obsessions are a poison all abused people encounter.

The great thing about writing is it gives me a way to accept both these poisons. Yes, I said "accept them." Toxins hurt because they are what the body cannot accept. Trauma is, almost by definition, what we cannot accept, what haunts us and remains indissoluble, forever unengageable. I will always love writing because it lets me engage with everything, even my own imperfections.

To comprehend means literally to take hold of; the kind of writing that I most respect starts from a premise of entering into all its characters with tenderness and thereby combines the great peace of understanding with a kind of control. Understanding is a kind of control, and control need not be a dirty word here. When Robert Heinlein invented the term grok to mean simultaneously know, eat, embrace, make love to and incorporate, he was invoking the secret logic of all writing, and the reason it is so comforting to write.

When you allow yourself to look at everything, nothing can scare you. Torturers become pitiable under that light and monsters woundable and human; trauma loses its shadowy terror and becomes merely another thing to pity, another thing to embrace and give comfort to.

When you allow yourself to know yourself completely, nothing in your mind can hurt you.

In one poem, Rich tells about an abused woman who ignores her own complicity -- and maybe even agency -- in her children's abuse. Rich says, "Because I have sometimes been [this woman], because I am of her,/ I watch her with eyes that blink away like a flash/ cruelly, when she does what I don't want to see." But the woman, it turns out, does the exact same thing. She "longs for an intact world, an intact soul,/ longs for what we all long for, yet denies us all ... What if ... in every record she wants her name inscribed as innocent? ... What has she smelled of power without once tasting it in the mouth?"

When Rich says that she has been this woman, when Whitman writes that he is both the bullets and the wounded slave, we taste our power for once, that ambiguous brittle taste.

In the spirit of daring to see everything, I'd like to look at the underside of the kind of writing I do. Or one of the undersides -- in a way, this kind of writing consists of nothing but undersides, and some of them are more conventionally beautiful than others. At some points in my writing and my life, my wanting to meet and make love to the enemy has been founded on an impossible fantasy of reconciliation, an urge to deny all harm and enfold the abuser in a seamless web of love that will obviate the need for all conflict and suffocate anger in its stifling warmth.

The fantasy of a reconciliation without anger and conflict and pain will never be realizable, and not even writing will ever be able to make it so.

And yet what it can accomplish is a reconciliation with anger and conflict and pain. "I make up this strange, angry packet for you," Rich says, "threaded with love."

Strange angry packets threaded with love are what get us where we need to go.

Yet even Whitman gets crazy sometimes in the omnipotence of his fantasy of making everything right. "Who need be afraid of the merge?" he writes. "Undrape ... You are not guilty to me, nor stale nor discarded,/ I see through the broadcloth and gingham whether or no,/ And am around, tenacious, acquisitive, tireless ... and can never be shaken away." It's rather frightening. Indeed, it's not surprising that his desire sounds a lot like, oh, yeah, an abuser's. As does mine in the fantasy I just mentioned: stifling people in a "seamless web of love" is what a lot of abuse is about.

In the exact same way, the Christian impulse to take on the pains of the world depends on an unconsciously sadistic theology in which someone, somewhere has to pay for being human.

And when Whitman says, "Unscrew the locks from the doors! Unscrew the doors themselves from their jambs!" he is simultaneously championing his freedom to look everywhere, and his right to override any possible boundary that another may set up. Merging with people who'd prefer to shake you away is a horrible desire, but not one that's terribly alien to me. If you merge with people the way the alien in the "Alien" movies does -- the way I think Whitman does -- you never have to endure people wanting something different from what you want.

In my own life, it's been hard for me, too, to negotiate conflict and love at once. Anger scares me, and I flee from it way more than I want to. It is much easier for me to be fearless in my writing than in life, which involves the present, messy, vulnerable body and its unmasterable, present feelings.

Sometimes I feel about my writing like a parent who sends her youngsters ahead of her into the dark, or as if I'm sending out mannequins shaped like me so that the enemy will be fooled. Text means a covering or weaving -- it is the root of the word "protection" -- and I have often thought of my writing as a second body I can place before my own, that can take attacks and beatings while my real body is left intact.

Fortunately, it is not a real person. But it does take attacks and beatings like a golden, indestructible decoy or a golem from whose unmenaceable back insults slide off and abuse melts like the mist.

My writing provokes people, and then nothing bad happens to it. I have often wondered about why I, in effect, invite abuse by writing things that are more than likely to make people angry. Now I understand why. Sometimes people get angry at me for saying things I had no idea would stir them up; sometimes they get angry about things that I knew would land like dynamite on the dumb and on the unreflective.

Forgive me for using these words, which are the ugliest in this essay. Let me say, rather, "on people who cannot bear to see certain things about themselves." My father was dumb and unreflective, and he hit me for saying things. He hit me for saying the truth. Now I say the truth over and over and people can do nothing to me.

Childlike of me? Yes. Unreconstructed, primitive, awkward: It is the child energy that provides the passion and pith of my writing. And writing is another way to let me love that clumsy, jubilant, obstreperous child.

It's true, I do get people to try to shut me up so I can experience the joy of their absolute impotence: I can't be shut up.

It is a pretty common trait of writers that we were people others attempted to shut up, or people made to keep secrets that gagged in our mouths. I wouldn't be honest if I didn't say that it's a thrill to make people angry with my work, under such circumstances, and to experience their anger safely.

Disgusting as it is to have something in common with Jerry Springer, I'm not about to hate myself for my provocativeness. I never say things I don't mean just to make people upset, and I very seldom use my writing to attack people. It's more that I don't care whether my writing makes them angry.

When attacks do come -- and they do keep coming -- it lets me experience other people's anger and find out again and again that I will survive it. Writing lets out the secret in all its glory without hysteria, without self-hatred and without violence, which is a tall order when you're speaking unpleasant truths.

Hey, it beats hitting people.

This is my way of fighting back.

As I've probably demonstrated, I am also oriented toward complexity, and appropriately enough, I feel ambivalent about that. One of the reasons I am oriented toward complexity is because of the complexity of my childhood and the complexity of abuse itself. In my childhood, there was love and destructiveness, nurturance and violence, and it is easy, not hard for me to see how the two things can be related. As Sigourney Weaver and the monster find out in the best of their movies together, "Alien: Resurrection," our impulse to nurture and our impulse to attack are sometimes hard to tell apart. They are sometimes the same thing. That is scary and it makes it hard to be a parent, but I am comforted acknowledging it, 1) because it is the truth, and 2) because it means there is no unadulterated evil, no evil that does not have something to do with vulnerability, something to do with wanting love, wanting comfort, wanting the end of fear, wanting what we all want.

Despite this, there's a more important, more significant way that complexity is the opposite of violence. It's the opposite of not being able to tolerate things, the opposite of the crack across the mouth. It's even the opposite of the wayward hand in the bed, because complexity allows for the existence of frightening and multiple impulses without their expression. Texts are complex in a way that violence can never be, and this weaving, this shag carpet, will always be bigger, more voluptuous, and ultimately more interesting than violence. I'm proud that I'm in the velvety camp.

Shares