God save us from spontaneous moms. In "Tumbleweeds," Gavin O'Connor's full-length directorial debut, a mother and daughter take to the road, escaping from mom's latest bad-choice husband (No. 4). The 12-year-old daughter pouts in the car, unhappy that her mother is simply repeating a tiresome pattern. Mom responds by handing over the hat she's wearing, urging her daughter to fling it out the window. Suddenly, enforced hilarity hits the accelerator, going from zero to 60 in no time as the two begin tossing clothes out of the vehicle, laughing uproariously. This zany, fun-loving mother has decreed that she and her offspring are going to start a new life or else, and in case you don't get the point, it's reinforced by the image of their car zipping down the road, garments flying gaily out of its windows. Yee-hah! Unstable moms are fun.

It's easy to understand why the idea behind pictures like "Tumbleweeds" and the recent Susan Sarandon-Natalie Portman vehicle "Anywhere But Here" is so appealing: There are so many times when modern families are anything but ordinary. It can be a relief to see parents and kids talking to each other in that casual, affable way, connecting as friends (albeit prickly ones) instead of constricting themselves into the usual rigid parent-child roles. What's more, parents and children often switch roles many times during the course of their lives: One might take on the responsibilities the other shirks, and vice versa. And the possibilities for exploring those kinds of relationships are endlessly compelling.

But at its core, "Tumbleweeds" is a deeply and disappointingly conventional picture masquerading as a free-spirited one. Janet McTeer's Mary Jo is the kind of mother we've seen many, many times before: fun-loving, irresponsible, irresistible to the opposite sex. She's so familiar that, her occasional thoughtless behavior aside, she's intensely comforting -- in other words, she's exactly what you want, and expect, a "bad" mom to be. Mary Jo is less an original, engaging character than an archetype, the kind of force of nature that's been hanging around in her black brassiere and housecoat for centuries, dangling a slipper from one eternally sexy instep. What could be more conventional than that?

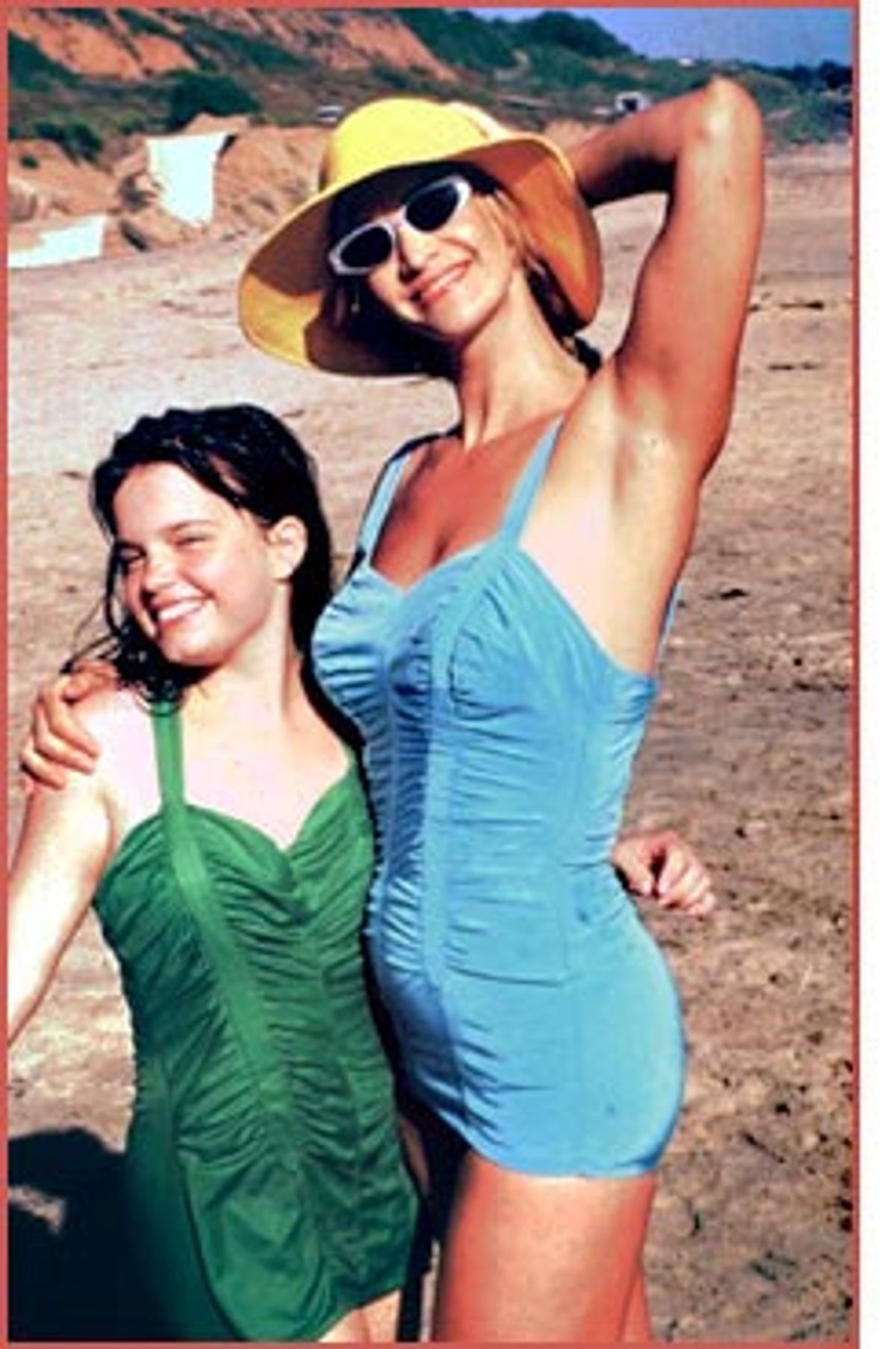

You can almost map out the direction of the mother-daughter relationship in "Tumbleweeds" within its first 10 minutes. Ava (Kimberly J. Brown), right at the portal of adolescence, finds herself having to deal with her mother's own brand of childish sexuality, her penchant for repeatedly choosing (and marrying) the wrong kind of men -- men who feel threatened by her sexiness and her independence.

Ava sees what her mother's problem is, and spells it out in no uncertain terms, grumbling as she loads her suitcases and her white mice into the getaway car yet again. She's the epitome of Wise Counsel, the urchin who's perceptive beyond her years. She's also bratty as hell, refusing, for example, to even acknowledge the trucker who stops on the highway to repair the duo's broken-down car. You may want to slap her, but her snottiness is no less than her mother deserves, and you end up granting her a kind of grudging sympathy.

What's frustrating about this is that Brown actually seems like a capable, intuitive actress, strapped into a lazily written role. (The picture was co-written by O'Connor and Angela Shelton; it's based on Shelton's own childhood experiences.) When we see Ava flirting tentatively with the classmate who's got a crush on her, or building a tower out of frosted doughnuts with her new best girlfriend, she radiates a youthful awkwardness that's both believable and beguiling.

But you also get moments like the one where she lets out a loud and stinky fart in a truck-stop restaurant. She and her mom -- who, earlier, had been explaining the nature of love to her daughter, all the while cleaning her fingernails with the tines of a fork -- rush out in a hurry, doubled over with laughter at the thought of what uproariously uncouth and joyous life forces they are. It's as if Shelton and O'Connor don't trust the actresses to tell their own story through simple words and gestures, which might have been at least marginally engaging on their own.

But there's so much that has to happen by the time "Tumbleweeds" settles into the groove that allows us to actually see Mary Jo and Ava dealing with their problems head on. The two must end up in the oceanside town of Starlight Beach, near San Diego, where Mary Jo seems to waste no time in finding the most redneck-y bars and bowling alleys imaginable (all the better to underscore the already well-established fact that this woman likes to repeat her mistakes). She must shack up with a basically decent numbnuts trucker, Jack (played with drab Fruit of the Loom ordinariness by O'Connor), who -- guess what? -- ultimately doesn't understand her or her daughter. Ava must befriend one of Mary Jo's co-workers, the gentle and intelligent Dan (Jay O. Sanders, in a pleasingly easygoing performance), thus taking matters into her own hands in hunting down a suitable mate for her wayward mom.

McTeer, a British stage actress who won a Tony for her performance as Nora in the 1997 Broadway revival of "A Doll's House," is a reasonably appealing actress: There's something rather open and touching about her face, and her North Carolina drawl lends her character an easy, playful kind of sensuality.

But her character seems constrained by the overt signposts O'Connor and Shelton have given her: Mary Jo, for all her commitment to good times, is a tragically romantic figure who likes vintage dresses and idolizes Ava Gardner (after whom her daughter is named). And her libidinous, just-verging-on-trashiness routine grows wearisome after a while, but I'm not completely convinced that it's McTeer's fault.

When Ava catches her mother with a new beau, her mouth frothing with toothpaste that she's tried to rinse out with a swig of beer (don't ask), it seems like nothing so much as a desperate attempt to show just how low Mary Jo will sink in the name of "fun." It's her daughter's job to redeem her, even as she's feeling her way toward adulthood herself, and if you can grasp the irony there, then you've got the basic idea behind "Tumbleweeds." These two rolling stones are supposed to be moving so fast they gather no moss. But the best they can muster is a predictable kind of bumpity-bump -- that only lands with a hollow thunk.

Shares