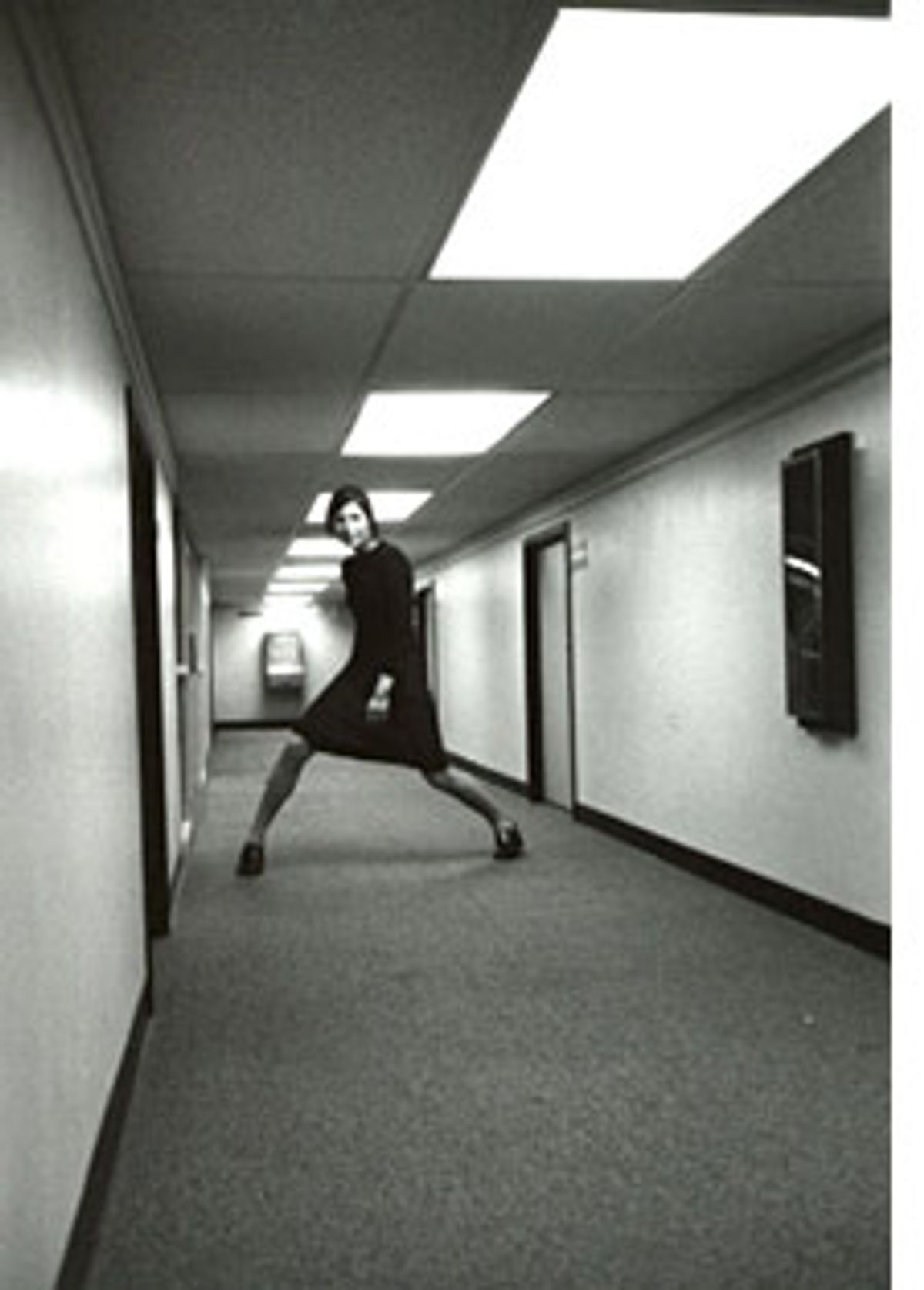

At a book reading last year in New York, filmmaker Harmony Korine sat behind a tiny tape player, pumping his fists to the Cranberries hit "Salvation." He simply pressed "play" and sat there, dressed in a robe and straw hat before a head-scratching audience at Barnes & Noble, until the song's last note. It was an absurdist exercise, borrowing context's power to twist otherwise familiar notions beyond recognition. At the same time, it was just a gloomily nihilistic stunt, provoking an audience with a heavy dose of childish motives and aimless antics.

This is the main knock on Korine as a filmmaker. While his supporters see tailor's marks behind his tattered on-screen images, his detractors argue that they're nothing but empty gestures. As for Korine himself, he says his visions are the result of putting different elements in place and, like a chemist, making sense of their explosions after the fact.

The book-reading scenario worked as all of the above. It was an explicitly weird drama cooked up by a bleak visionary who would later try to pick a fight with an innocent spectator. But it also served as a dizzyingly smart bit in light of a salvation-themed poem he would read so earnestly afterward. And it was also an example of his clever ways with music.

It's clear in his films that Korine has a well-tuned ear for music. In "Gummo," he smartly mined sounds as disparate as impossibly dark death metal and Roy Orbison's "Crying" for shared strains of despair. And the image of a gas mask-wearing Werner Herzog listening to Dock Boggs in "Julien Donkey-Boy" cut an oddly faithful representation of the claustrophobia weighing on Boggs' early vintage folk.

As a director, Korine knows how to let music make a scene (see "Gummo's" meditation on a

mock-sultry femme licking her lips to Buddy Holly's

"Everyday") and how to let it serve one. (Consider the same

movie's tender picture of mother and son curling

silverware and tap dancing, respectively, in the air of

Madonna's "Like a Prayer.")

Having worked so nimbly with music and having spread his aesthetic beyond film to photography and fiction with projects in the past, it comes as no great surprise that Korine would make a record.

And his aesthetic being always torn along the frayed edges of

experimentation, it comes as even less of a surprise

that it would sound like his first album, performed by Korine and his friend, Brian

Degraw, under the name SSAB Songs.

Which is to say that the album won't offer much to those not already interested in its star. For those who are, it's a studied extension of the folk tradition he's both called to mind and laid to rest in a bed of leaves fallen by time and acid rain.

The duo's eponymous debut is a 27-minute album

featuring one lone track strung together by multi-track

minds. A scratchy string sample starts things off with a classicized whisper, but it's not long before the duo breaks out pots and pans to bang in some shopworn kinks. From there, the record is a deliberately muddy mess of banjos, ghostily strained vocals, found percussion, electronic whirs and subterranean recording techniques.

Like the ethnomusicology-pirating Sun City Girls, SSAB Songs place distant folk music's inherent weirdness on a pedestal while also using it as a springboard to go further out. Reverent takes on banjo-driven folk melt in and out of static, picking on innocuous themes and veiling garbled lyrical snippets sounding something like "Little Jimmy's mother rotten/Mr. Ninja whore." Korine and Degraw file through sounds in a frenzy seemingly guided by both semiotics and narcotics.

Though anybody can do atonality, not everybody can do it well. And though anybody can bang on pots and pans, not everybody is Harry Partch. Much to their credit, SSAB Songs land closer to the side of Partch. They've certainly stirred up a primordial soup of sound, but when the ingredients come together, when they're allowed to sit and stew, there's just enough flavor to make it edible and just enough mystery to make it intoxicating.

Shares