By Christmas, Colette was settled in her new apartment. The last day of the old year, 1908, brought something rare to Paris: snow. It came down all night, and it was still falling "like a chenille veil," "crisp as taffeta underfoot," "powdery and vanilla" on the tongue, when Colette and her dogs went out to play "like three madwomen" in the deserted streets.

They came in at dusk to doze by the hearth. "Here I am again," writes Colette, "facing my fire, my solitude, and myself." The snowfall and the dying of a tumultuous year made her pensive, and she gave herself over to reveries of seasons past, "the form of the years," "the winters of the childhood." When she roused herself, she found her shepherd bitch "steaming like a footbath" at her feet, the bulldog and the gray cat sleeping, and she was "astonished," she writes, "to have changed and aged while I was dreaming."

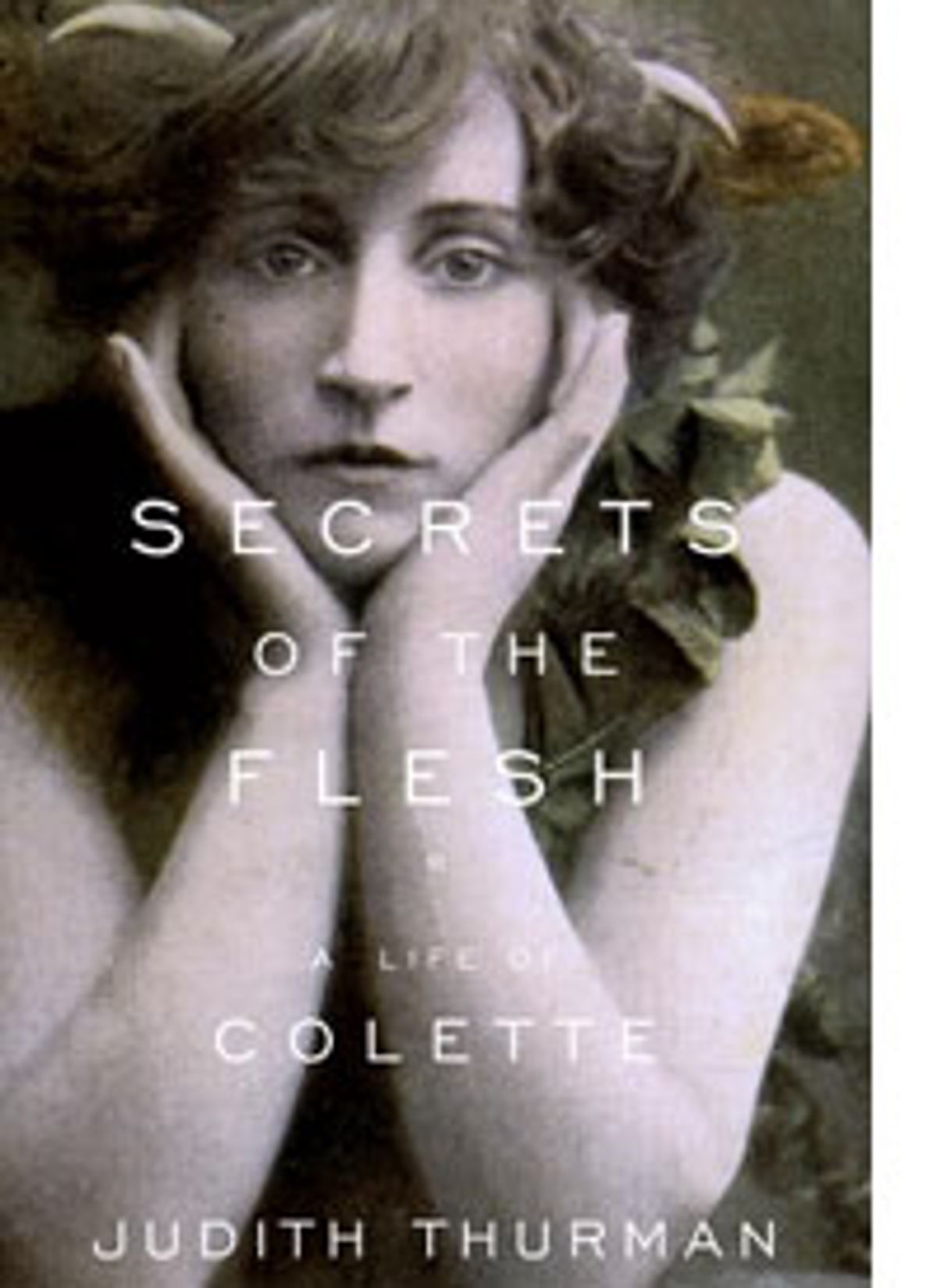

There are many suicides in Colette's work -- a fact she never noticed, she told a friend in the 1930s, until it was pointed out to her by a reader. Juliette's isn't among them, but it sharpened her consciousness of mortality. Sitting by the fire that New Year's Day, she held up her hand mirror and found, in the "dark water of the glass," the first fine "claw marks" of age. What makes them so poignant to her in the French sense of the work -- poindre means to pierce -- was that she could still see beyond them to the "adorable," "velvety," "elastic," "rosy girl" who was gone forever.

"You have to get old," Colette told herself then, with more bravura than conviction, trying -- as she often did -- to disarm an unpleasant truth by stating it. She was three weeks shy of thirty-six: a youthful woman no longer young by the standards of her age and facing the mortality of her beauty. "Don't cry," she commands, "don't clasp your hands in prayer, don't rebel: you have to get old. Repeat the words to yourself, not as a howl of despair but as the boarding call to a necessary departure." Colette goes on to unwind the imaginary "ribbon" of a life well lived. After addressing a series of lyrical, stoic blandishments to herself -- the kind of sentences that would make her wince as a more seasoned writer -- she concluded: "If you haven't lost your hair, left your teeth behind you one by one, nor your spent limbs; if the dust of eternity hasn't, in the final hour, blinded your eyes to the wondrous light -- and if, at the end, you hold a loved hand in you own -- then lie down smiling, go to sleep, happy one, go to sleep, lucky one."

Colette would die at eighty-one. At the end, her supple dancer's legs had failed her. She wore false teeth, could barely see, and she was deaf, but she held the hand of the man who loved her. As it happened, she had, practically to the final hour, kept her head, which is not, curiously enough, on her departure checklist. Braced against physical disintegration -- the loss of beauty, sensual acuity, appetite, strength -- Colette forgets or omits to fear the loss of her mental powers. Productive to the end, and secure in that aspect of her integrity, she would be remarkable among modern writers -- perhaps the great women in particular -- for a sense of self not vested in her mind.

Shares