Depending on who's doing the talking, convicted cop-killer Mumia Abu-Jamal is

either a race-maddened psychopath cynically manipulating the gullible into

helping him get away with murder, or an innocent artist and revolutionary

railroaded onto death row by the racist forces of oppression.

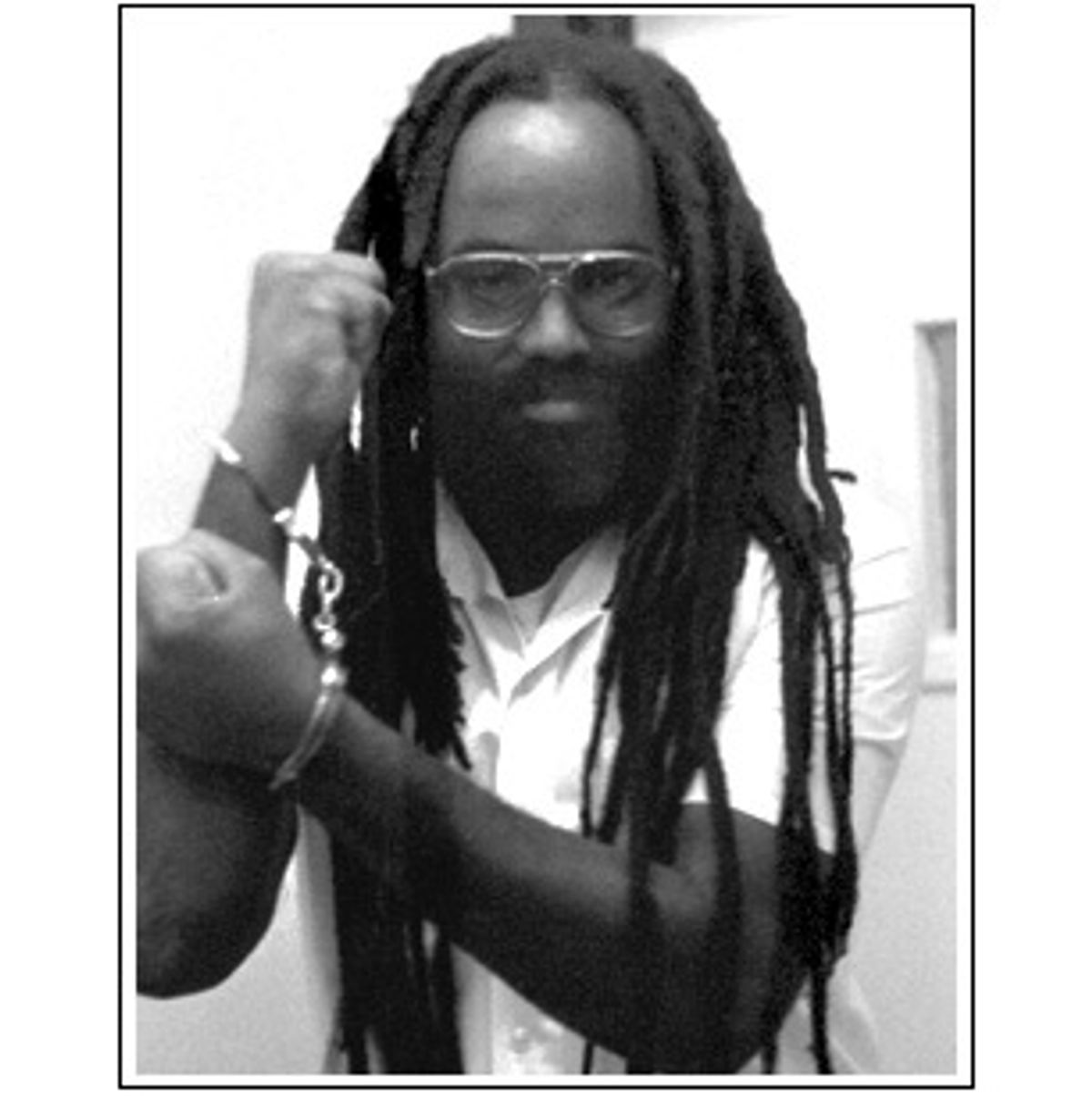

Whatever the truth of the matter, the dreadlocked Mumia (so famous that

he's now down to just one name) is a potent reminder that we're far from

through with the past when it comes to racial politics in America.

Centuries of racism, and the corrupt government structures that

enforced it, are still a radioactive part of our living memory and will remain so for at least another generation. That means there will almost

certainly be more of these racial cause cilhbres in our future. After all, we've only had one generation since the triumphs of the civil rights movement to unlearn 350 years of hate and mutual suspicion.

Maybe it's because we're still wearing our egalitarian training wheels that

the overarching issue of the role that race plays in the Mumia case has

eclipsed other critical questions that bear analysis in their own right.

One of those is Mumia's fitness to be held up as a racial hero and martyr

in the first place. Who gets to decide that question?

The basic facts of the criminal case against Mumia are simple. Around 4 a.m. one December night in 1981 in a seedy area in Philadelphia, a 26-year-old

police officer named Daniel Faulkner stopped a car going the wrong way down

a one-way street. A 27-year-old cabdriver (and radical journalist) named

Mumia Abu-Jamal (ni Wesley Cook) was parked nearby and

saw the officer bludgeoning a man who had gotten out of the stopped car --

a man who just happened to be Mumia's brother, 25-year-old William Cook.

What happened next is in dispute. But soon after, Faulkner lay dead on the

street, having taken one bullet in the back and one

between the eyes. Mumia slumped nearby, shot in the chest. Responding

police found Faulkner with most of his head blown away and Mumia fallen to

the curb with both his holster and his gun empty.

Seventeen years, two appeals and two execution warrants ago, a jury

found Mumia -- who has never told his side of the story -- guilty of first-degree murder. His most recent date for execution -- Dec. 2 -- was

stayed pending further legal appeals of his conviction.

Mumia's supporters claim that the police rushed to judgment in their haste

to nail someone for Faulkner's death and didn't pursue exculpatory

leads. (Some witnesses claimed they saw a third man flee, for example, and

Mumia's empty gun might have been a different caliber than at least one of the bullets

found in Faulkner's body.) But Mumia hardly cut a sympathetic figure; his radical politics (he'd founded the Philadelphia chapter of the Black Panthers at age 15) did not endear him to the police or prosecutors. His supporters believe that his trial was essentially a sham.

Over the years, as news of Mumia's fate has spread, demonstrations have been

held on his behalf all over the world. Celebrity backers have championed his

cause, documentaries have been made about him and Mumia himself has

reactivated his moribund journalism career from death row.

Police organizations have been equally energized by his

case -- from the opposite perspective. On a number of occasions, they've had to be coerced into providing security for Mumia benefit concerts and for his celebrity supporters; meanwhile, they've funded appearances by Faulkner's widow to counter what they see as the glorification of a cop-killer.

Right-wing commentators and conservative groups have joined the fray, so much so that smearing Mumia and his supporters has become a staple of the shock-show set.

So much for the left and the right. But what about African-Americans?

Contrary to stereotype, blacks as a group tend to be social conservatives,

very tough on crime and not at all sympathetic to radical chic trends. Furthermore, they

are unlikely to know, or care, about characters like Mumia.

David Bositis, a senior political analyst at the Joint Center for Political

and Economic Studies who has analyzed political trends in the black

community for years, says he wouldn't squander a survey question on Mumia.

"I suspect that, on a national survey, probably 10 percent or fewer would

be aware of him," Bositis says. "I tend to doubt that there'd be a

groundswell of support for him. Why him? There are many better examples --

[Abner] Louima, [Amadou] Diallo, Rodney King even."

Those blacks who are aware of Mumia have long exhibited ambivalence

toward his cause. Mumia is a working (if unconventional) journalist and

a past president of the National Association of Black Journalists

(NABJ) chapter in Philadelphia, yet the NABJ "takes no position" on his

case. (Individual black publications have published Mumia's work, however,

and some have called for his release or retrial.)

Those black leftists and nationalists who support Mumia know that they need

to win the hearts and minds of average black people over to his cause.

Angela Davis, for example, bemoans the lack of involvement of black

ministers in the battle. "I am going to challenge the clergy in

Philadelphia to join the push to stop the execution of Mumia," Davis told

the Village Voice recently.

The Rev. Al Sharpton, interviewed in the same article, agreed, "These ministers have

the political clout to let [Pennsylvania] governor Ridge and others know that

they would not allow them to do this. This cannot be seen just as 'a

left-wing movement' -- there must be across-the-board resistance. I am

going to tell them that if they do not stand with me to stop the execution,

the blood of Mumia Abu-Jamal will be on their hands."

Most black folk might just disagree with that conclusion. Instead,

they may believe Mumia has only himself to blame for his predicament and

that the campaign to save him really is just a left-wing movement of the

type they long ago rejected.

Besides his involvement with the Panthers, Mumia was such an ardent

supporter of MOVE -- the radical black nationalist movement that was

eventually firebombed by the city -- that it cost

him his perch in journalism and sent him instead into the driver's seat

of a cab to support his three children.

In truth, Mumia is the kind of angry black man that many blacks

instinctively reject. He scares most black people, just as he scares most

whites.

This makes sense: Blacks have for so long been on the receiving end of

black violence and crime that they are sick of it, and are deeply skeptical

of any calls for racial solidarity on behalf of convicted murderers like

Mumia. According to Bositis, when black respondents are asked about

drug penalties, they overwhelmingly favor harsh penalties.

Furthermore, a huge majority -- 75 percent -- support mandatory

"three strikes" laws that put repeat offenders in prison for life.

But blacks' reality is a complicated one, because they live in a world

bounded by residual racism on the one hand and black-on-black crime on the

other.

Sixty-nine percent believe that racial profiling "usually" happens, for

example, and 44 percent say they have been stopped "for no

apparent reason" while driving. (Many refer to it as a case of "DWB" -- driving while black.) Fifty-six percent say police brutality and harassment are still serious problems where they live.

Yet New York City blacks widely supported a white man, Bernard Goetz, when

he shot fleeing black thugs in the back. In the crack- and gun-ridden

1980s, no one suffered more than black people; one result of this is that they have no trouble sending violent blacks to their just rewards.

In the Mumia case, his supporters understand that black community

involvement is the missing link in their argument that he was targeted

because of his race and his politics; they are working strenuously to

galvanize blacks in the battle to save Mumia's life. His lawyers speak at

black churches; Rev. Sharpton harangues his fellow ministers; grass-roots

activists try to activate the grass roots.

But if Mumia himself really wants to gain the sympathy and support of

regular blacks, he might want to cut his hair, change his name back to

Wesley and join the prison gospel choir. Blacks know racism, and

they know it's become ever more subtle, and therefore ever more difficult to prove. But they also know they can't let racism drive them around the bend and deprive them of their ability to think clearly. They are instinctively suspicious of a man who's found wounded and woozy with an empty gun and the body of another human being nearby in a seedy part of town at 4 a.m. Especially when that man is a "wild-eyed radical" with whom they have nothing, except race, in common.

That's why, even though the usual suspects are making the usual claims on

behalf of "black Americans" in the Mumia case, actual black Americans are

by and large sitting this one out.

Shares