As a phenomenon and as a person, Andy Kaufman was hard enough to explain during his lifetime. Now, 15 years after his death, understanding him is, if anything, harder.

Kaufman was the most unconventional comic during the late '70s and early '80s, devising strange little routines that often made, at best, only a kind of oblique sense and sometimes carried more than a whiff of hostility toward his audience. Even his regular stint on the hugely popular "Taxi" didn't dilute him: He channeled the weirdness of his stand-up act into his character, the immigrant-as-moonbeam Latka, without any sense of compromise.

What's peculiar about his legacy, though, is that he doesn't seem any more comprehensible today then he did when he was alive. Seeing old "Saturday Night Live" footage of the comedian with his little record player, anxiously waiting for his cue as the scratchy "Mighty Mouse" theme cruised on by (he would lip-sync only to the line, "Here I come to save the day!"), doesn't help illuminate him any. Kaufman wasn't of his time; he wasn't of any time.

Kaufman died of cancer at age 35. Today it almost doesn't seem as if he's gone, because he doesn't seem like anything we could have dreamed in the first place. It's more as if he'd been scooped up by a space vessel and whisked back to that place, wherever it is, he really belonged. You could miss him, sure, but somehow time seemed to rush in pretty quickly to fill the space he once occupied. It was as if he'd been something of an embarrassment to the gods, an aberration: "We didn't actually mean to send him down; it was a bit of a mistake." Before long, it was easy to ask yourself if he'd ever really been here.

Milos Forman's distressingly disjointed biopic "Man on the Moon" doesn't attempt to explain Andy Kaufman, which is one good thing about it. What was the genesis of the little schemes he devised with his co-writer and collaborator Bob Zmuda (a co-executive producer of "Man on the Moon"), like the sleazy lounge performer alter-ego Tony Clifton? Was there a streak of evil in him that caused him to cook up little pranks, often at his audience's expense? Why did he decide he wanted to wrestle women? Did he like playing Latka on "Taxi," or did he constantly resent it?

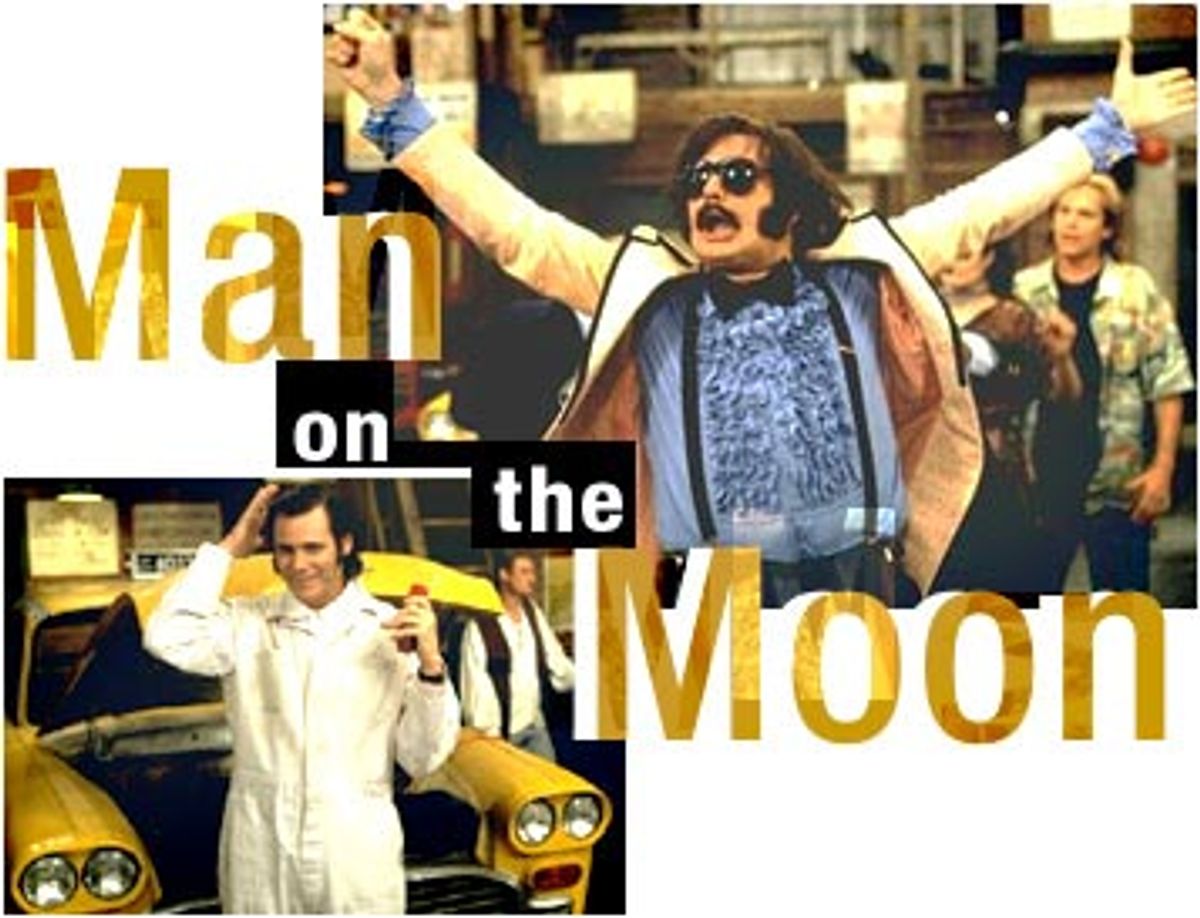

These are questions Forman never attempts to answer fully. Instead, he just floats them in the ozone like little imaginary boats, trusting that star Jim Carrey's characterization of Kaufman will touch on all of them, either as vaguely or as succinctly as an expressionistic poem -- Forman doesn't seem to care which. The result is a movie that's too conventional to capture Kaufman's insanity and too haphazard, too shapeless, to recapture Kaufman's energy

in any meaningful way. Carrey's remarkable performance simply seems stranded. It's the heart of the movie, and yet it also seems strangely swallowed by it, thumping to get out.

It's frustrating that the movie starts out as cleverly as it does. Carrey, looking more like Kaufman than I ever would have imagined, addresses the camera directly: "Thank you for coming to my movie," he says meekly, unblinking. He then prattles through a half-sensical explanation of how any movie about his life would probably be filled with untruths, after which he announces that the movie is over. The credits roll; music plays. "I am not fooling. Goodbye," he tells us. "Go." He leaves, but then peeks back in from the edge of the frame.

That prologue is a more perfect summation of what Kaufman was about than anything that comes after it. It's the only sensible way to try to sum up a man who could invite a whole audience out for milk and cookies after a big Carnegie Hall show, a man who would test the limits of an audience's patience by reading them "The Great Gatsby" all the way through, a man who some believe may have even faked his own death.

But before long that exquisite beginning starts to read more like an apology than a declaration, as if Forman were simply excusing himself from clear storytelling. We see Kaufman meeting up with his manager, George Shapiro (Danny DeVito), for the first time. As they sit in a restaurant discussing the possibilities of their partnership, a small teardrop of ooze starts to drip from Kaufman's nostril. Shapiro does his best to ignore it; when he's not looking, Kaufman quickly switches it to the other nostril (it's fake, of course). The gimmick has a stupid kind of brilliance, and in that sense it's pure Kaufman.

But before long Forman starts to blur and smear the details, and the story -- written by Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski, whose "The People vs. Larry Flynt" suffered from similar incoherence -- loses shape and meaning. When Forman simply allows Carrey to re-create Kaufman's comedy routines, the picture skates along nicely. But Forman often makes Kaufman's story unnecessarily hard to follow. Fairly early on he introduces the idea that Kaufman was unsatisfied with his role as Latka on "Taxi" (the picture features several members of the original cast as themselves, although DeVito's Louie isn't accounted for).

But then Forman conveniently forgets about the discontent, instead focusing on Kaufman's increasingly odd routines and his alienation from people who used to support him, like "Saturday Night Live" executive producer

Lorne Michaels (who also appears as himself). Late in the movie -- admittedly, after it's been suggested that Kaufman hasn't been getting as many comedy bookings as he used to -- we see Kaufman responding with dismay to the news that "Taxi" has been cancelled. But we have no sense of what he'd been feeling about the show, or whether his earlier misgivings had been resolved.

Similarly, we get some half-formed ideas about Kaufman's commitment to meditation and his rather robust sexual appetite. His relationship with collaborator Zmuda (the amusing Paul Giamatti) is sketched out in the most cursory manner. And Kaufman's girlfriend Lynne (Courtney Love) is introduced in a maddeningly offhand way and then treated throughout the rest of the movie as if we'll simply understand, with no explanation, her role in his life. She starts out as the first woman Kaufman wrestles on TV. Later we see her and Kaufman out on a date. Then suddenly she's a regular fixture in his life, but we have no sense of how this might have happened. Love has an exceedingly open, expressive face, but her scenes feel dropped into place -- they don't seem integrated into the rest of the movie.

What's most frustrating of all is that even Carrey -- Forman's star, for God's sake -- feels dropped into place. Carrey gets Kaufman's hunched, slumpy body language perfectly. His phrasing, with its pauses and tics, mirrors Kaufman's beautifully, even though he never comes off as a mere mimic. And then there's the way he gets that Kaufman look about the eyes -- that knowing simpleton's gleam.

But there's a disjunction between Forman's wanting to preserve Kaufman as an enigma and his efforts to show him to us as a human being, particularly when he's suffering through his illness and he and Lynne travel to a faith healer who might be able to cure him. Forman can't ask us to accept a character as an enigma and then expect us to react to his pain as if we were watching a melodrama.

None of us needs to be convinced to feel compassion for Kaufman and the illness he had to endure. But Forman just doesn't know how to integrate Kaufman the unearthly, mysterious genius with Kaufman the human being in pain -- or, perhaps, he just doesn't know enough to accept that they can't be integrated.

When Kaufman and Lynne seek out that cure, you see honest hope in Carrey's eyes, and it should be enough to break your heart. Or it should make you feel mildly uncomfortable, seeing a side of Kaufman that you'd never glean from his stage routines or his TV performances. But instead of either of those things, the moment just feels vaguely dishonest -- like a dramatized speculation about what a plane-crash victim might have thought about in his last seconds of life.

To be fair, Forman had the cards stacked against him from the start: How do you show the interior life of a man who was, to put it bluntly, just fucking weird? But "Man on the Moon," despite Carrey's brilliance, isn't even much of a noble failure. It's an ode to a man of mystery that's so maddeningly unfocused it comes close to diluting his genius.

The movie's title comes from a 1992 R.E.M. song, a sideways appreciation of Kaufman that is, in typical R.E.M. fashion, impressionistic and swimmingly amorphous, all loose strings and unsquared corners. It's an incredibly wistful song -- an elegy for someone who was taken before his time -- but it's not a sentimental one.

Somehow that song, even with all its unspecific poetry, manages to render a more intimate and heartfelt view of Kaufman than Forman's belabored movie does. "If you believe they put a man on the moon," R.E.M.'s Michael Stipe sings, the beginning of a conditional statement that never quite resolves itself. I can't explain in words what that line means in relation to Andy Kaufman, but then, I can't explain Andy Kaufman, either. I would have thought that space vessel would have taken him much farther from this world than the moon -- but maybe the point is that he's closer than we think.

Shares