Many historians believe that our first ritual was the one we created to celebrate the beginning of a new year. Makes sense, but how do you decide when the beginning begins? Interesting problem -- and it has been solved in different ways from society to society, century to century and place to place.

Usually, a naturally recurring event would mark the date of a new year. An annual change in the weather, the beginning or end of a growing season, or the return of an important food source (animal or vegetable) would signal the start of the festivities.

It was the ancient Romans, however, who decided to celebrate New Year's on the first of January, a day when nothing special was happening in nature. At the time they had a calendar that divided the year into 10 months. The first month was March and the last was December. At the end of December, everyone stopped counting for 60 days until March got started. It was a very confusing policy.

In 153 B.C., a Roman general noticed that the Egyptians had filled in the blank time with two new months and he mentioned it to the Roman Senate. The politicians loved it, immediately introduced January and February and marked the first of January as the official opening day of the New Year. This was an extraordinary change from the past. Suddenly it was Man taking charge over Nature.

After the fall of the Roman Empire, Europe was confused as to which day should be used to start the new year. Some communities liked autumn for the start of their new year. We still feel that influence: The school year starts in the fall, many corporations begin their fiscal year in the fall and, as we are never allowed to forget, the new television season begins in the fall.

Originally, the French tied the start of their new year to the arrival of Easter Sunday. They celebrated the rebirth of the year along with the birth of Christ, combining two important festivals of regeneration in one. The fact that spring was a time for good eating didn't hurt. The produce was younger and the wine was older. The French have always understood the importance of coordinating their gatherings and celebrations with what's good to eat.

Britain celebrated New Year's Day on December 25th until William the Conqueror had himself crowned on January 1, 1067, and thought it would be nice to move New Year's to that date.

Italy liked their New Year's on Christmas Day until 1582, when Pope Gregory XIII decreed that the Church follow a new system (humbly named the Gregorian calendar), which chose January 1 as its starting date.

The transition from the old to the new year is filled with superstitions and elaborate rituals. Many societies feel that what you do on New Year's Day you will do the whole year long. Some people say that if you like your work and want to continue it in the coming year, you should carry a symbol of your profession throughout the day. If you wear something new, it will help you get new things during the New Year. You should also make an effort to get up early on New Year's Day, not lend anything and avoid crying.

A baby in diapers is often used as an image, symbolizing the old Germanic idea of welcoming in the New Year "child" while ushering out the "old man" of last year. At my age, I'm not thrilled with that imagery, but in the interest of even-handed journalism I'm passing it along.

Money plays an important role in the celebration of the New Year. Many people make an effort to pay all their bills before the turn of the year. But remember (if you plan to follow this custom), you need to pay them off before New Year's Eve! You don't want to start the New Year laying out money; this could start a trend that might continue all year long. There's also a belief that you should keep some money in your pocket on New Year's Eve and New Year's Day. And if you have children, put some money in their pockets to diversify. Hide some money outside your house on New Year's Eve, and take it back in on New Year's Day -- this may send a signal to the universe that money is meant to flow in this year.

In Scotland, people believe that the first person to come into your house in the New Year will set the tone for the coming months. That person is referred to as the "first footer," and is sometimes chosen by the family in an attempt to control its own luck. In case you'd like to try out for the job, the person should be tall and dark-haired, but not flat-footed or have eyebrows that meet in the middle. This "first footer" is often also called the "lucky bird." He may bring a present to the household, but it should be something that will be used up inside the home and not taken out again -- single malt whiskey is always appropriate.

In France, there was a time when people used New Year's Day as an excuse to pay a visit to their associates or to people with whom they hoped to be associated. Very often, the people they went out to see were not home because they were out trying to visit people with whom they hoped to associate. The result of all this visiting was a general lack of reception: Almost no one was at home. But you left your visiting card to show you had been there. Eventually people gave up leaving cards in person and began popping them in the mail. That's how our present custom of mailing New Year's cards -- which evolved into our custom of sending Christmas cards -- got started.

In farm communities it was important to protect the crops and animals from evil spirits at the moment of change from the old to the new year. The most reliable technique for keeping these spirits on the move appears to be the blowing of horns combined with the banging of drums. Additional well-respected procedures include shouting, whistling, ringing bells and generally making a nuisance of yourself during those first few moments as the old year changes to the new. Making noise has often been part of the rituals associated with beginning something new. We bang on a door to have it opened; we bang on a pan to start the New Year.

Many cultures believe that the food and drink of New Year's Eve will have an important influence on life during the coming year. The ancient Romans thought that a table represented a "field of fortune" that could be used to send a signal to the gods. They would cover their New Year's table with all the foods they loved -- sending a message of abundance for the future.

A primary object for every important celebration is an attempt to reconcile opposites: death and rebirth at Easter, light during the darkest days at Christmas, giving up the old while accepting the new at a birthday party. What we eat and drink on these occasions has been carefully chosen to assist with this balancing act, and the meals on New Year's Eve and New Year's Day are perfect examples of our desire to show both sides of our personalities.

One group of food is always simple, inexpensive and easy to make (like the New Year's Day lentil soups of Italy). These foods show that we are not wasteful, and deserve good things in the coming year. The second group of foods is expensive, rare and often extravagant (champagne and caviar). These foods send the opposite signal: "Excuse me! But since I have the capacity to be a simple, thrifty and deserving person, could I have more of this good stuff in the New Year?" In most cultures, both groups of foods are served at the same time and balance each other out.

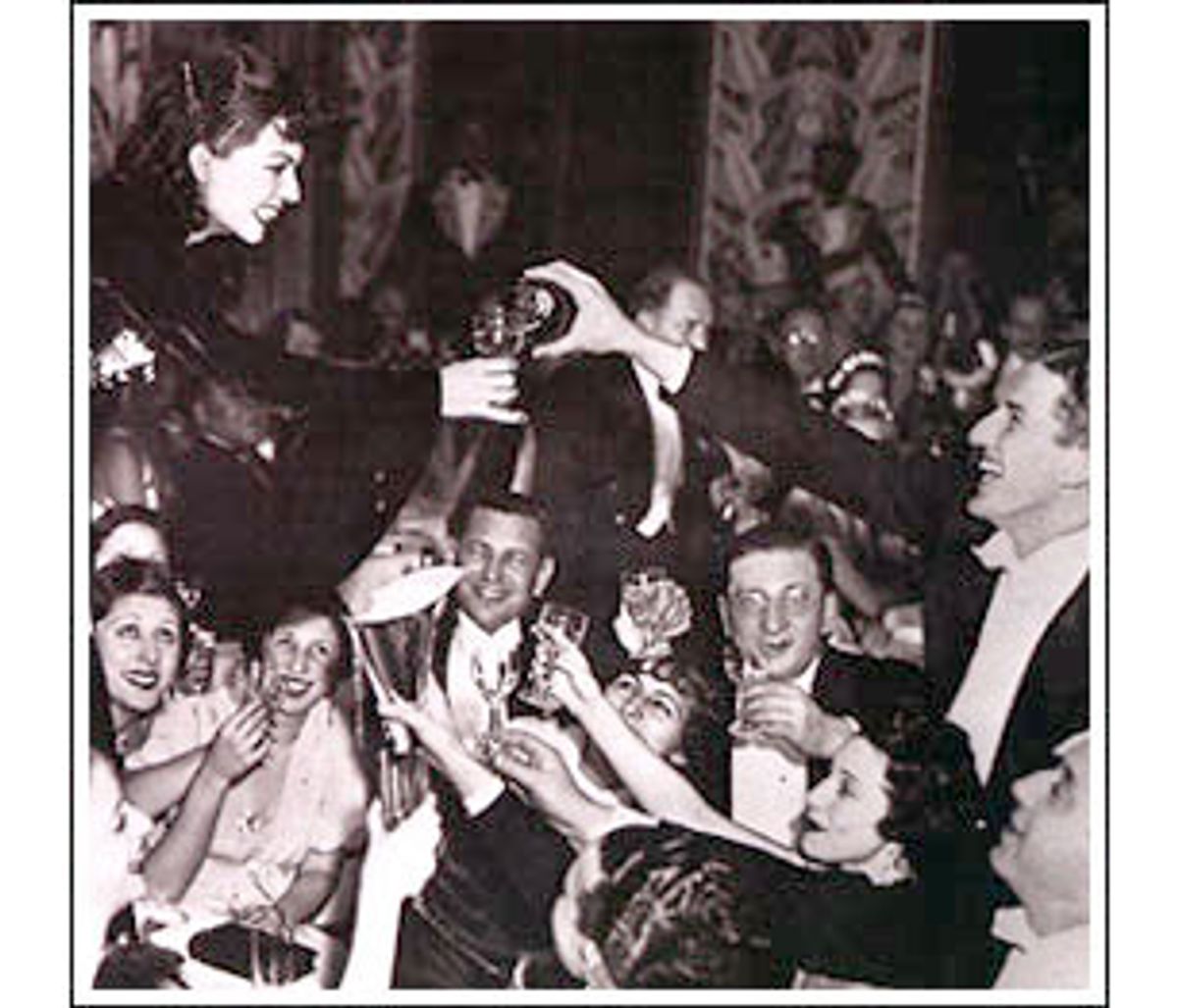

The moment when the old year becomes the new is always important. You are supposed to stay up and be clearheaded and happy as the bells start to toll. It is a turning point, and you want to be able to consciously direct your fate at this very significant moment. The whole idea of a New Year's Eve party is to establish a happy setting as the New Year begins. Of a good beginning cometh a good end.

Shares