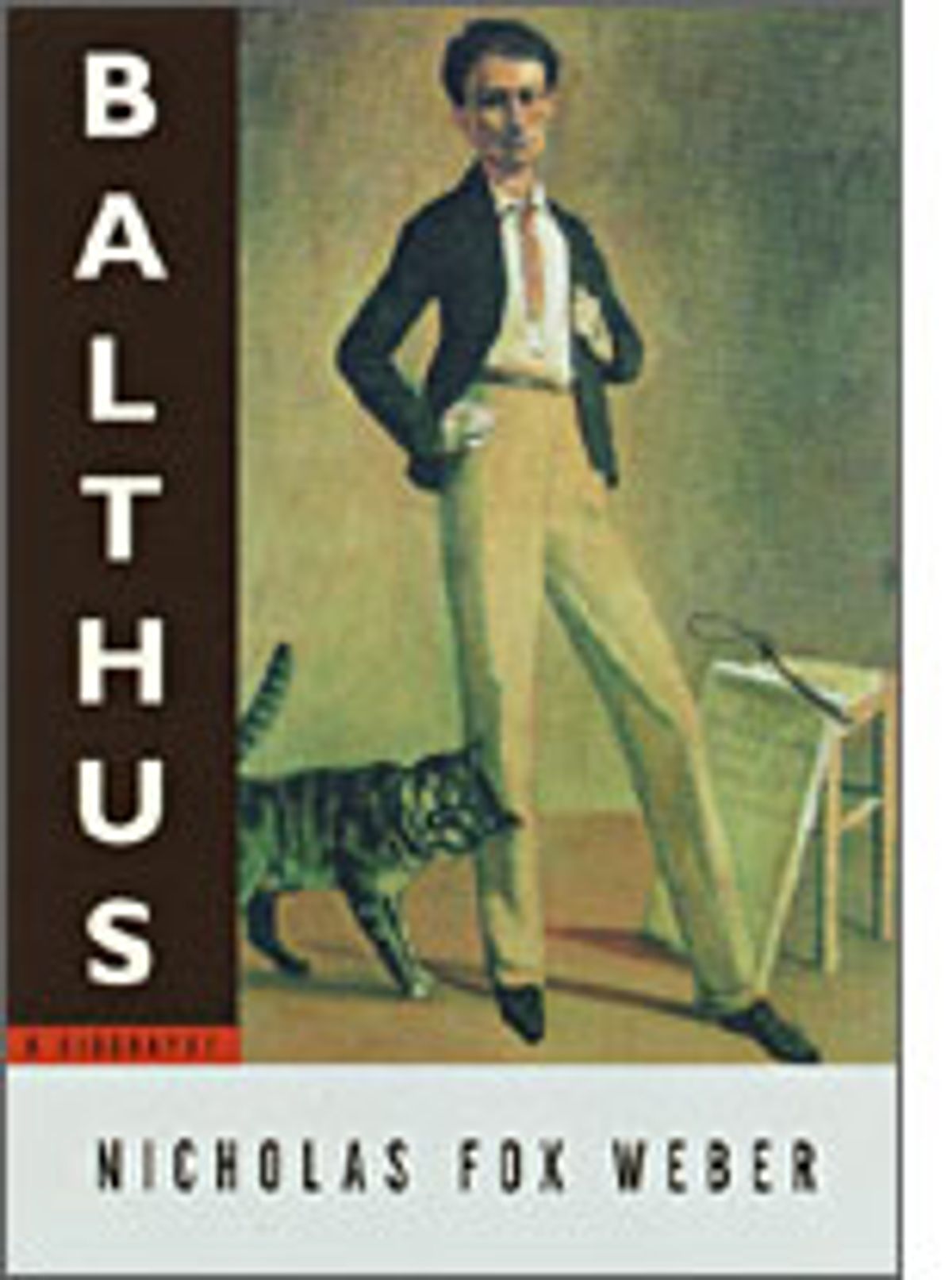

Arts journalists are a notoriously catty lot. Those who can't do, bitch. Schadenfreude is a smirk away. Nicholas Fox Weber, despite his status in the art establishment (he's the director of the Joseph Albers Foundation), isn't any different. His "Balthus: A Biography" isn't a straightforward hatchet job, though, but a botched scalpel one.

Balthus, a brutal snob, a ruthless social mountaineer, a lech and a nasty anti-Semite, is no innocent. Yet for much of his long life -- he was born in 1908 -- he's been handled with kid gloves by the culturati, and for good reason. Hacks who have been extended the "rare" courtesy of an audience with Balthus Klossowski, Count of Rola -- "the last legendary painter" (in David Bowie's clichi) -- leave La Rossinihre, his Swiss chalet, chirping with delight, charmed out of their wits. Even arch modernist sorts usually dismissive of anything figurative or traditional give him their approving nod, because his subject matter -- nymphets in bloom -- has that ambiguous je ne sais quoi.

Weber, a self-described devotee, nearly falls for the dapper Pole's charm himself. He's deferential, and his intentions are honorable: to argue for Balthus' artistic greatness. But then this Boswell knees his Johnson, attacking him personally if not professionally. Specifically, having set out to disprove rumors that the artist's stories of his past are fabrications, he winds up enumerating the falsifications in numbing detail.

Balthus is not a count. He's not related to Byron (though he is Byronic), nor is he related to the last kings of Poland. On his mother's side he's the grandson of an illustrious cantor whose name still resounds in Poland. His father may or may not have been Jewish or gentry. His childhood was not pampered but haphazard -- a series of shabby digs in Paris, Lausanne and Berlin, with the dirty ears of genteel poverty -- and, it seems, unhappy, his father absent, his mother acting the poetess.

Such family friends as Bonnard, Valiry, Vuillard and Rilke (his mother's lover) doted on the lad and his elder brother, Pierre (later a distinguished literary critic and Sade scholar), and Balthus grew up with an acute sense of his superiority. Rilke noted his precocity and collaborated with him on "Mitsou," a touching tale about a boy and his cat, when Balthus was 14; the adolescent's drawings received wide acclaim. And though Balthus wasn't always a lady-killer (as his tortured courtship of Antoinette de Watteville -- his first wife and a real aristocrat -- proved), the old roui's still had more women than Weber's had hot dinners. Friendships with Artaud and with the patron Marie-Laure, Vicomtesse de Noailles, rounded out Balthus' unsentimental education.

In fact, Balthus' decline, like those of Dali and Warhol, two other ambitious outsiders, can be traced to his entree into society, however cafe. Weber seems offended, even envious, at the idea of Balthus' dining at the best tables on a false passport; he forgets that the artist's talent is what got him to those tables. Feigning impartiality, Weber claims to regret poking holes in Balthus' reminiscences, spotting discrepancies and catching him out. He characterizes understandable lapses of memory about Parisian locales, models, old studios, dealers and contemporaries (Balthus was in his 80s when he endured Weber's po-faced inquisition) as evasions or amusing, self-serving lies.

Attending a major retrospective of Balthus' work in Lausanne in 1993, Weber is appalled at the count's capers with a young model; it never occurs to him that Balthus is playing with his image as a pedophile. Then the biographer, as if he were a procurer, parades his daughters before Balthus to see if he'll get a rise out of the old goat. The liberated-dad act is disgusting.

When it comes to the oeuvre on which Balthus' reputation will ultimately rest, Weber fails completely. With a flair for the obvious, he lays on the Freudian terminology to explain that a banana is not always a banana. His queries and speculations verge on the inane. Worst of all, he fails to convince us of Balthus' greatness. He cites a youthful influence, Piero, as the model for Balthus' odd proportions and composition, Courbet for his color and sensuality, Morandi for his tone. Weber puffs Balthus up until, like Aesop's frog, he explodes.

In spite of his friendships with Picasso, Mirs and Giacometti (with whom he was especially close), modernism is anathema to Balthus. He is, in truth, a reactionary, and his legacy is uncertain. For the past 20 years he's parodied himself, painting the occasional "Balthus" for market. Getting down with demimondaines, shocking prudes in America and posing as the last living relic of the ancien rigime is no assurance of lasting fame. Fittingly for a man of such rarefied taste, Balthus may be better remembered for his skills as the interior decorator of the Villa Medici in Rome than for his efforts with the palette.

Balthus is not a major painter but a minor, novelty one; he is to little girls what Stubbs is to horses. He stands out at the end of the century purely by default: His betters are dead.

Shares