When I, a newlywed, am asked to produce my ring, the ritual goes all wrong.

I am supposed to brandish a good-sized diamond to a brood of women who will coo over it like it's a towheaded newborn boy. But my ring is Depression-era, very small, with seven tiny bead-set diamonds. Like many humans, I tend to use my hands a lot, and this ring is both sparkly and indestructible. I love it. Two month's salary? Tee-hee. Try one week's.

Of a teacher's salary, no less. My husband is a first-grade teacher.

Generally, jobs that have traditionally been the province of women --

hair care, cooking, teaching -- are all occupied by men at the top levels.

When a man does your hair, cooks your dinner or teaches you, you know that you are getting the best service available. You are being tended by a stylist, chef or professor.

This is changing, of course. Many women have infiltrated the top

ranks of their traditional professions, but that doesn't mean that many men have been eager to don a pink collar. (Although Southwest Airlines' show tunes-belting male flight attendants do come to mind.) Visit any teaching supply store on a Saturday and you'll see what I mean. When we go, my husband, Josh, is usually the only guy in there. But he's the one who's shopping; I am carrying the

stuff. When it's revealed that he's the teacher, most people jump to this conclusion: "Wow, that must be a really good school."

I must admit, I never had thought much about teaching before Josh entered

graduate school to get his master's degree in education. This was when I got my

first taste of my unique role, and he, of his. He was a man in a woman's

world. His fellow students were boy-crazy and cute, in a junior-high kind of way. They took it as their mission to edify him on a number of topics: Why "girl butt" is the worst thing ever on a guy; the relative merits of cold, sweet, frothy, coffee-flavored beverages from Starbucks and the Coffee Bean and Tea Leaf; and the latest plot twist on "Party of Five." Josh perfected one line for the latter topic, which he rendered in the uneven tones and incorrect emphases of someone practicing colloquial business English: "Julia is such a bitch."

Teachers tend to congregate at mediocre Mexican restaurants. Take a look

around next time you're at an El Whatever. You will know them by their

cardigan sweaters, large blended drinks and air of wholesome bad-assery. I

mean that as a compliment: Many teachers deal daily with children whose

families have been destroyed by poverty, drugs and violence, while often teaching in facilities far worse than prisons. Yet, they soldier on and try to remain

upbeat for the sake of these small, forgotten people.

Whenever I agree to join Josh for a night out with his fellow teachers, Josh is always the only person at the table who isn't saying, "Oh really, I shouldn't," while scarfing down basket after basket of delightfully greasy tortilla chips. One time, several of my husband's colleagues took advantage of their margarita-induced drunkenness to guiltily admit their still-passionate love of Sanrio products. These are Josh's friends?

Being the wife of a grade-school teacher is like being Queen Elizabeth's husband, Ol' What's-his-name. Whenever I find myself confronted with a group of women on the other side of Josh -- be they classmates, colleagues or parents -- I tend to shy away.

Groups of women make me nervous: I feel that they are acting out social

scripts that I never received. I am the master of blurting out the wrong

thing in unmixed company. At my own bridal shower, I declared that, rather

than be there, I'd prefer to have bamboo shoved under all ten of my

toenails, in what I thought was a conspiratorial tone, just as the room went completely silent, as rooms tend to do at such moments.

On a recent Saturday, I was at a school picnic talking to some parents

of Josh's students. I stumbled into a sentence where I was about to

say, "I was totally screwed." But then I took in the scene -- children

everywhere, frolicking on the field, hanging off of monkey bars, skipping,

singing -- and me, with an audience of three nice ladies. I stammered, "I was,

I was, I was ..." and took a moment to come up with the appropriate phrase.

The moms were watching me intently. "Rather inconvenienced" for the save!

I took this as a sign that it was time for me to clean up my verbal

lexicon. Josh has taken to grade-school teacher swearing, which includes

such classic phrases as "Feldercarp!" "Cheese and crackers!" "Sugar!"

Now that our once-robust expletives have become flaccid and watery through overuse, alternative swear words actually seem to make sense. We've invented some new ones (feel free to adopt at will): "Manilow!" "Crust!" "Cruise control!"

For me, the problem was not merely a matter of changing four-letter words. My entire vocabulary -- which suggested that I was still hanging out in the Beverly Center, circa 1985 -- needed some serious revision. It was long past time to retire the words "sucks," "blows," "totally," "rad" and, of course, "awesome," from my quotidian speech. After all, I am almost 30, for the love of, for the love of, uh, dogs.

Picnics, parent conferences, faculty meetings -- like many things that women

do, teaching comes with all kinds of extra work. For example, before the

school year started, Josh and I once spent an entire day cutting out bubble

letters and construction-paper decorations for his bulletin boards -- a fascinating part of the grade-school teacher's cosmology.

Have you ever wondered why all school bulletin boards have those scalloped

edges, and why the bubble letters? It's simply practical. Bubble letters are

easier to cut out. And as for the scalloped edges, well, it's quite difficult to get the background paper aligned to the edge exactly. So you slap some corrugated scalloped stuff on the ragged edges. Voila! Attractive and educational.

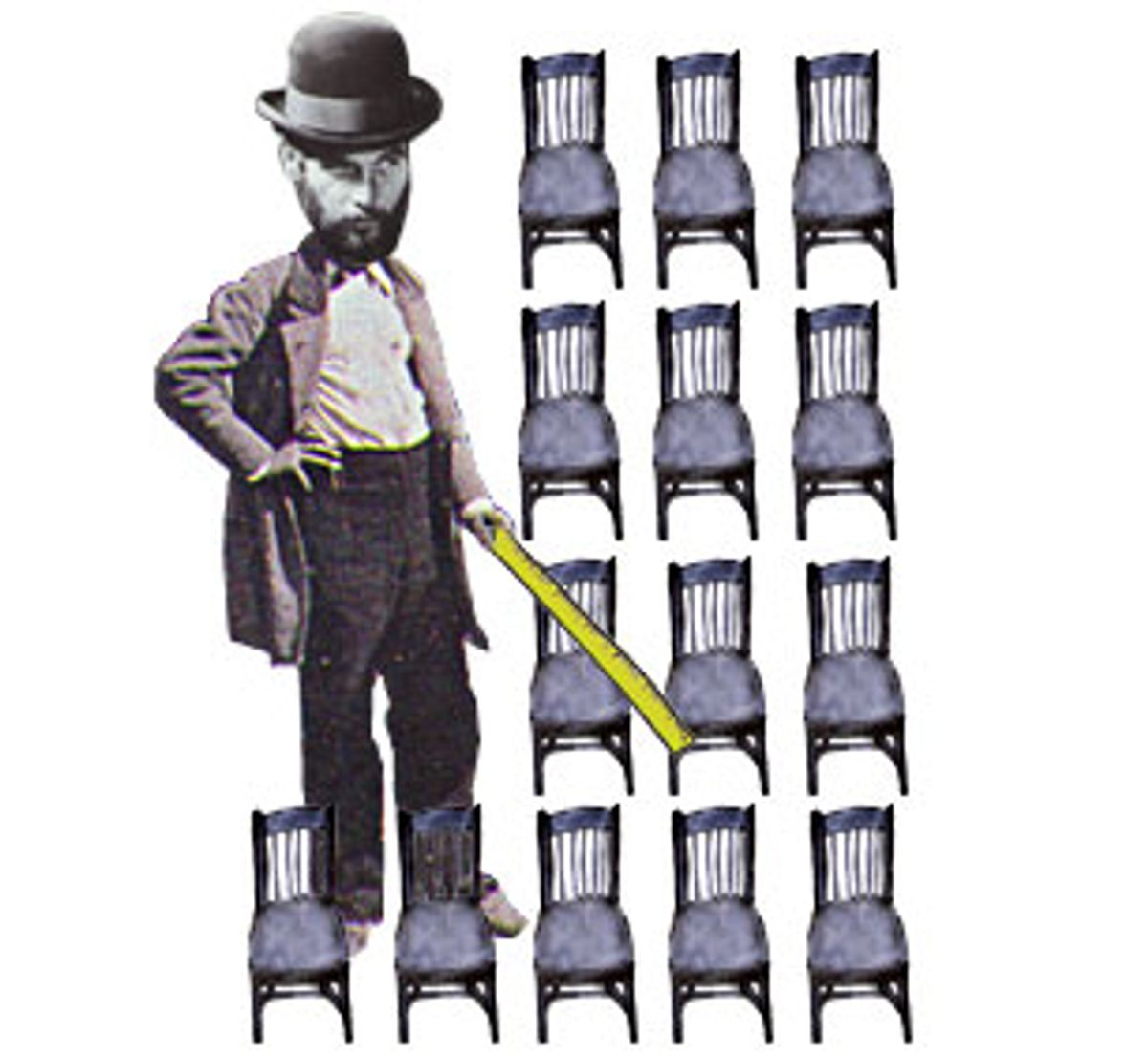

Looking around my husband's classroom -- at the wee chairs and the bins filled

with crayons and markers, the picture books and stuffed animals, the fat

pencils waiting for little hands -- I had a wash of emotions. First, maudlin

sentimentality of the kind that overcomes adults when they are greeted with

evidence of how many years have passed since they were themselves runny-nosed and losing teeth. Then, I felt sympathy for the children who are entering the system. What can you say to a beginning first-grader? "Chin up, kiddo, you've only got 12 years to go?"

And last, I felt awe at what my husband does. I had a glimmer of the feeling

that men must have when and if they confront what pregnancy and childbirth

actually entail: I could never do that.

Josh is the Zen master of children. He exerts an almost unworldly calm and

civilizing influence on the little ones. "They are people first," he says.

"You just have to trust them."

His children have a 15-minute period in the beginning of the day, when

they are coming in, and allowed to do whatever they want. Lately, this has

meant playing their own version of live-action Pokémon: They chase each other around while screaming nonsense words from the game. It is annoying. But it's also their own time. Josh wasn't going to tell them that they couldn't play the game. "They'll sort it out for themselves," he said, philosophically.

And he was right.

During circle time, one girl, with a thoughtful expression on her face, piped up, "I don't think we should play Pokémon in the morning anymore. I think we get too excited and silly and it's hard to calm down. I think we should only play it on the playground." Another boy raised his hand. "I don't know what Pokémon is, I don't have it, and when everyone's playing it, I can't play."

Hearing this story brought an unconscious truth to the surface. When I met

Josh, I was running around and shouting nonsense words metaphorically, and,

well, literally. Under his patient tutelage of love and trust, I too have

begun to make positive decisions about my own behavior.

Josh gets called Mrs. Valle a lot at the beginning of the school year. He's always the only man at ladies' birthday brunches. A mother of one of his students nervously asked him what she should get him for Christmas. While shopping for his school clothes, we joke that perhaps he should just start wearing corduroy jumpers with wooden apple pins on them. At night, when he tells me about the day's activities -- making Napoleon hats out of paper, listening to jazz, writing spontaneous poems and cutting up vegetable sushi with safety scissors -- I feel contact exhaustion. I sit on a chair all day and type and talk on the phone and feel like I'm working really hard. It's hard to believe that some people don't consider teaching a real job. I can't imagine anything more real.

Shares