One summer afternoon on a porch in Madison, Wis., someone handed me “The Fun House,” Lynda Barry’s 1987 collection of comic strips. The bright blue book was open to a strip about some bored kids who wonder “what would it be like to cross 23rd Street and take a field trip up there where we never hardly were before.” As they attempt to cross the busy street, one of the kids is hit by a car. The rest of them run back to their neighborhood “thinking if we can go fast enough, it didn’t really happen.” Having expected something like “Peanuts” with a gag line, I felt as if I’d been punched in the stomach.

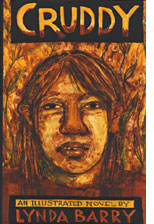

Sometimes, though, feeling as if you’ve been punched can be a good thing. Barry’s latest book, the richly illustrated novel “Cruddy,” is as wrenching as Dorothy Allison’s “Bastard Out of Carolina,” but funnier. Here, 16-year-

On a bus in the middle of nowhere, sitting next to her passed-out father who has recently given her a black eye and bruised ribs, Roberta wants to write a letter to someone, but she can’t think of anyone who would want to hear from her. Finally, she starts a letter to Jesus but can’t think of anything to say. “Have a Good Summer,” she writes, “and Stay Crazy.” Barry is master of scenes that make us want to laugh and then, immediately afterward, cry.

The patterns of the novel parallel patterns of abuse, in which fear and pain so often follow close on the heels of laughter or tenderness. In the novel’s present, we find Roberta in the dirty kitchen of “a cruddy rental house” where her mother is yelling at her for hitting her sister, Julie, with the Cutex nail polish remover bottle — a normal enough situation in a house with two teenage girls. But during this scene, Roberta remembers another time her mother got mad at her, picked up the telephone receiver and bashed her in the face with it. “A broken nose,” Roberta writes. “A boxer’s nose. One of my many distinctive features.”

“Were you like, in a car accident?” someone asks her, referring to “the various smashed aspects” of her face. She is scrawny from the year of malnourishment on the road with her father, and she has always looked like a boy — “a pug ugly one was how the father said it.” Her father calls her Clyde and tells people that she is a boy. The sheriff they meet at the horrific Knocking Hammer slaughterhouse calls her Ee-gore, but her ugliness only encourages him to try to use her as a receptacle for his perversions. Luckily, her father has given her Little Debbie, the knife that saves her life many times but also dooms her to feeling that she is as “corroded” as her parents.

Like Allison, Barry shows how completely children are at the mercy of the adults around them. But the issue is not uncomplicated. Barry characterizes children as both the most vulnerable and the most resilient creatures on earth. Most of the adults in Roberta’s life have tried to victimize her, but she remains analytical, cynical, funny and less confused about right and wrong than she thinks she is. She knows, for instance, that her mother gets maddest not when Roberta does something wrong but “when she remembers all the ways she’s been ripped off in life.”

But the abuse takes its toll. While Roberta’s romantic side clings to the equation “Truth plus Magical Love equals Freedom,” she struggles with the urge to jump in front of trains. She fights her own lack of remorse for the bad things she has done either in self-defense or out of spite by carving “I’m sorry” into her arm, but when her friend the Stick asks her, “Are you sorry?” she admits she isn’t.

Barry is an expert in the too-often neglected vernacular of working-class childhood in urban America, and Roberta, with her haunting and often jubilant voice, is a typical Barry kid, screwed by circumstance but still searching for integrity. “Cruddy” adds to Barry’s already impressive body of work another fine novel that is tender, goofy, scary and thrilling.