Advertisements urging parents to love their kids and keep them off drugs dot urban bus stops across America. Anti-drug commercials fill Channel One in the nation's schools and the commercial breaks of network TV -- most notably a comely, T-shirt-clad waif trashing her kitchen to demonstrate the dangers of heroin. We've come a long way from Nancy Reagan's clenched-teeth "Just Say No."

Few Americans, however, know of a hidden government effort to shoehorn anti-drug messages into the most pervasive and powerful billboard of all -- network television programming.

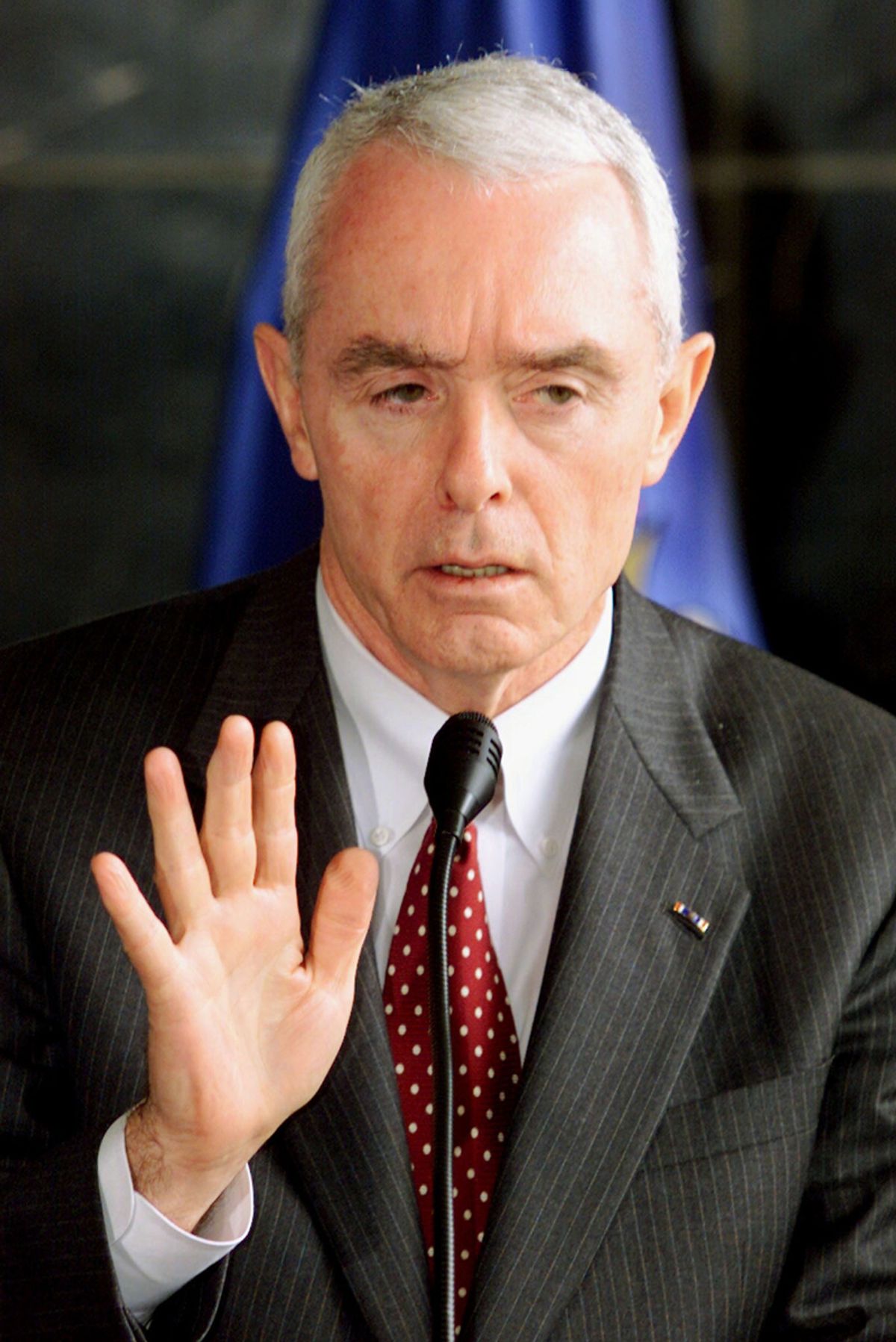

Two years ago, Congress inadvertently created an enormous financial incentive for TV programmers to push anti-drug messages in their plots -- as much as $25 million in the past year and a half, with the promise of even more to come in the future. Under the sway of the office of President Clinton's drug czar, Gen. Barry R. McCaffrey, some of America's most popular shows -- including "ER," "Beverly Hills 90210," "Chicago Hope," "The Drew Carey Show" and "7th Heaven" -- have filled their episodes with anti-drug pitches to cash in on a complex government advertising subsidy.

Here's how helping the government got to be so lucrative.

In late 1997, Congress approved an immense, five-year, $1 billion ad buy for anti-drug advertising as long as the networks sold ad time to the government at half price -- a two-for-one deal that provided over $2 billion worth of ads for a $1 billion allocation.

But the five participating networks weren't crazy about the deal from the start. And when, soon after, they were deluged with the fruits of a booming economy, most particularly an unexpected wave of dot-com ads, they liked it even less.

So the drug czar's office, the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP), presented the networks with a compromise: The office would give up some of that precious ad time it had bought -- in return for getting anti-drug motifs incorporated within specific prime-time shows. That created a new, more potent strain of the anti-drug social engineering the government wanted. And it allowed the TV networks to resell the ad time at the going rate to IBM, Microsoft or Yahoo.

Alan Levitt, the drug-policy official running the campaign, estimates that the networks have benefited to the tune of nearly $25 million thus far.

With this deal in place, government officials and their contractors began approving, and in some cases altering, the scripts of shows before they were aired to conform with the government's anti-drug messages. "Script changes would be discussed between ONDCP and the show -- negotiated," says one participant.

Rick Mater, the WB network's senior vice president for broadcast standards, acknowledges: "The White House did view scripts. They did sign off on them -- they read scripts, yes."

The arrangement, uncovered by a six-month Salon News investigation, is known to only a few insiders in Hollywood, New York and Washington. Almost none of the producers and writers crafting the anti-drug episodes knew of the deal. And top officials from the five networks involved last season -- NBC, ABC, CBS, the WB and Fox -- for the most part refused to discuss it. The sixth network, UPN, failed to attract the government's interest the first year of the program; it joined the flock this current TV season.

The arrangement may violate payola laws that require networks to disclose, during a show's broadcast, arrangements with any party providing financial or other considerations, however direct or indirect. (We'll explore that issue in a separate article Friday.)

Legal or not, the plan raises a host of questions. "It sounds to me like a form of propaganda that is, in effect, for sale," says media watchdog Bill Kovach, curator of the Nieman Foundation. Terming it a "venal practice" and "a form of mind control," he adds, "It's breathtaking to me that any [network's] sense of obligation to the viewing audience has a dollar sign attached to it."

Andrew Jay Schwartzman, president of the Media Access Project, a public interest law firm, says, "This is the most craven thing I've heard of yet. To turn over content control to the federal government for a modest price is an outrageous abandonment of the First Amendment ... The broadcasters scream about the First Amendment until McCaffrey opens his checkbook."

Former FCC chief counsel Robert Corn-Revere, now at the law firm Hogan & Hartson, calls the campaign "pretty insidious. Government surreptitiously planting anti-drug messages using the power of the purse raises red flags. Why is there no disclosure to the American public?"

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

The ONDCP, the powerful executive-branch department from which the anti-drug effort emanates, is more commonly known as the drug czar's office. McCaffrey, a Vietnam War hero, directs it and sits on Clinton's Cabinet.

The office oversees spending of nearly $18 billion annually for such activities as fighting peasants growing coca in Latin America, helping interdict drugs entering the United States, local law enforcement and research and treatment. Though Bob Dole savaged non-inhaler Clinton as weak on drugs during the 1996 presidential campaign, Clinton has quietly been Washington's most aggressive anti-drug warrior. Says Dr. Thomas H. Haines, City University of New York medical school professor and chair of the Partnership for Responsible Drug Information, "Clinton spent more federal money in the war on drugs in his first four years than was spent during Reagan's and Bush's 12 years combined."

But in the fall of 1997, the most prominent public face of America's anti-drug crusade belonged to the private Partnership for a Drug-Free America. With major funding from a foundation fueled by the estate of the founder of Johnson & Johnson, along with other corporate support, the partnership bills itself as a "nonpartisan coalition of professionals from the communications industry."

Founded in 1986, the partnership has garnered hundreds of millions of dollars a year in donated media space and time, hitting its peak with over $360 million annually in both 1990 and 1991. But by 1997, donated media had declined to $222 million, the group was suffering a decrease in both the quantity and quality of its donated space and time, and the targeted teens had become inured to its oft-parodied "This is your brain on drugs" message.

The partnership's chairman, James E. Burke, began to lobby Congress to add money for paid ads to the drug czar's budget. Though then-House Speaker Newt Gingrich didn't need much convincing, other Republicans had to overcome two objections to a new federal expenditure of this size: Some wondered if the highly visible effort would just let the president and other Democrats claim credit as crusading anti-drug warriors; others worried about showering money on Clinton's perceived allies in Hollywood. "Some on the Hill wanted to just cut a check to the Partnership for a Drug-Free America," says one Capitol Hill insider.

Burke and the partnership eventually won the Republicans over. Rep. Jim Kolbe, R-Ariz., chairman of the House appropriations subcommittee that funds the media campaign, says, "We were persuaded by the Partnership for a Drug-Free America to spend tax dollars" to get the message out in prime time.

So in October 1997, Congress approved an extravagant plan to buy $1 billion worth of anti-drug advertising. The drug office got about $200 million annually for five years, beginning in fiscal year 1998, and was charged with targeting both the nation's youth and "adult influencers." The office billed the job in a 1998 press release as "the largest and most complex social-marketing campaign ever undertaken."

Approximately two-thirds of the office's ad budget was targeted at TV; the rest was sprinkled among everything from billboards to radio, newspaper, magazine and Internet advertising.

But Congress, feeling that the networks should also contribute to the war on drugs, drove a hard, two-for-one bargain: for every ad the government bought, it demanded another of equal value for free.

"It was contingent on a private-sector match," says John Bridgeland, former chief aide to Rep. Rob Portman, R-Ohio, who fought for the deal. "No member of Congress was going to pass new money for this without a match" -- that is, without that second ad slot.

Indeed, with only $1 billion budgeted to it by Congress, the office refers to its "five-year, $2 billion ... campaign." McCaffrey himself called it "our major prevention initiative, the $2 billion five-year Anti-Drug Media Campaign."

The government's paid ads began running on five of the nation's networks, all but lowly UPN, during the summer of 1998. One TV ad features a scruffy, plain-spoken teen who boasts of a sterling academic record before succumbing to marijuana and getting thrown out of the house. Then there's the one mentioned above: the waif-like Gen-Xer taking a frying pan to her kitchen, supposedly to demonstrate the terrors of heroin addiction. The actress is budding young star Rachael Leigh Cook of "She's All That."

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

How did the networks' two-for-one ad deal evolve into a plan to insert messages into programming content? Bridgeland says that wasn't the original idea. "I don't think we thought of programming content as a match ... [It] was not actively discussed," he says -- a point that Kolbe echoes.

The half-price deal got a mixed reception from the networks. NBC, the most highly rated network in 1998, with the most valuable ad slots, initially balked for some three months. The chief ad buyer for the drug czar's office, Zenith Media Services Inc. CEO Richard Hamilton, oversaw negotiations with the networks. NBC, he says, made a "business decision."

Then in the ratings doldrums, ABC had fewer qualms. Says Bart Catalane, former CFO of ABC Broadcasting: "Given the way ad-spending had been going, we needed every category, particularly a growing one like government spending. We wanted to grab every share we could." Indeed, the first year of the office's ad campaign, ABC grabbed nearly $30 million worth, half again as much as Fox, its nearest rival at $20 million.

Even high-flying NBC eventually went along; participants say that the network came around after hearing about its rivals' barrels of government cash. Half a loaf was considered better than none, especially from a baker with a projected five-year supply of flour. "This was before the market got so tight," says one former contractor to the drug-policy office. "This was before all the dot-com ads. When we started, the market was less bullish."

But selling time at half price never went down smoothly, and Hamilton reported back that the networks weren't happy. Hence, in the spring of 1998, Alan Levitt, who runs the office's advertising campaign, and Zenith boss Hamilton cooked up the novel idea of using programming -- that is, the plots of sitcoms and dramas -- to redeem the second ad slot owed the government.

"We did this to make it a little bit more obtainable to participants," Levitt says. "I know it's allowed us to make some deals we wouldn't normally make before. There are some media outlets that have not been able to -- are not financially able, or they don't have the structure where they can give us print space or programming or time. And so we can make it more flexible for them."

That spring of 1998, Hamilton and Levitt agreed that sitcoms and dramas that met with the drug-policy office's approval could be used in lieu of the ad slots still owed to the government. Formulas would be applied to determine the cash value of these embedded messages, and the networks would then be free to resell the commercials they otherwise would have given to the government.

Ultimately, the ONDCP developed an accounting system to decide which shows would be valued and for how much. And its officials began to vet television shows in advance, sometimes suggesting alterations. Tapes of the show as broadcast were sent to the office or its ad buyer to be assigned a final monetary value, which would then be subtracted from the total the particular network owed the office.

The drug office and its ad buyers received advance copies of the scripts from most networks, often more than once as a particular episode developed over time. In some cases, the networks and the office would wrangle over the changes requested. Says an office contractor, "You'd see a lot of give and take: 'Here's the script, what do you think?'" He adds, "I helped out on a number of scripts. They ran the scripts past us, and we gave comments. We'd say, 'It's great you're doing this, but inadvertently you're conveying something'" off-message.

This contractor prevailed upon the producers of the WB's "Smart Guy" to change the original script's portrayal of two substance-abusing kids at a party. They were originally depicted as cool and popular; after the drug office input, "We showed that they were losers and put them [hidden away to indulge in shamed secrecy] in a utility room. That was not in the original script," this contractor says.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

The scheme worked like this: According to a set, numerical formula, the drug-policy office assigned financial value to each show's anti-drug message. If the office decided that a half-hour sufficiently pushed an endorsed anti-drug theme, it got valued at three "units," with each unit equaling the cost of one 30-second ad on that show. Hour shows presenting an approved story line were valued at five units, equal to the cost of five of that show's 30-second ads. (Ads on higher-rated shows -- shows that deliver more eyeballs -- cost more. Therefore, shows with higher ratings, which disseminated ONDCP's message more widely, achieved higher valuations.)

For example, the drug czar's office bought approximately $20 million of advertising time from News Corp., the Rupert Murdoch-owned global media conglomerate that owns Fox. Therefore, News Corp. owed the United States an additional $20 million in matching ad slots from its inventory of ad time.

To partially meet its "match," and thus recoup some of the ad time owed the government, Fox submitted a two-episode "Beverly Hills 90210" story arc involving a character's downward spiral into addiction. Employing the formula based on the price of an ad on "90210," the episodes were eventually valued at between $500,000 and $750,000, says one executive close to the deal. As Kayne Lanahan, senior VP at News Corp One, Fox's media and marketing operation, describes it, "There were ongoing discussions with Zenith. They looked at each episode and how prevalent the story line was." Lanahan adds, "We occasionally show [them] scripts when they're in development, and the final script, and then send a tape after it airs."

This Salon reporter was able to identify some two dozen shows where specific single or multiple episodes containing anti-drug themes were assigned a monetary value by the drug czar's office and its two ad buyers: Zenith and its eventual replacement, Ogilvy & Mather Worldwide.

In return for, apparently, several episodes with anti-drug subplots, highly rated "ER" redeemed $1.4 million worth of time for NBC to be able to sell elsewhere. "The Practice" recouped $500,000 worth of time for ABC to sell if it wished. And anti-drug messages woven into "90210" redeemed between $500,000 and $750,000.

Other shows with episodes that redeemed ad time for the networks during the 1998-99 season include: "Home Improvement," valued at approximately $525,000 for ABC; "Chicago Hope," valued at probably $500,000 or more (CBS); "Sports Night," a valuation of around $450,000 (ABC); "7th Heaven," valued at around $200,000 (WB); and "The Wayans Bros." with its relatively paltry ratings, kicking in only approximately $110,000 (WB).

In addition, the following shows also redeemed ad time last season, though this reporter could not determine their monetary value: "Promised Land" and "Cosby" on CBS; "Trinity," "Providence" and several episodes of the four teen-oriented Saturday-morning live-action shows on NBC; and "The Drew Carey Show," "Sabrina the Teenage Witch," "Boy Meets World" and "General Hospital" on ABC.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

The process unfolded over time, with some scripts reviewed more than once. When a draft of the script was available, the network sales department would alert the drug czar's ad buyer. And then the office's Alan Levitt, or his colleague Jill Bartholomew, became involved. They'd get a copy of the script -- though ABC maintains it was an exception to this step -- and then provide "a quick turnaround" with their reactions, says one insider.

The drug-policy office typically verified the particular episode as being on-message and appropriate for a match. "If a kid was offered a joint and said, 'No thanks,' in a way that was on-strategy, it was that simple. It was a judgment call by the network, the agency and the client," says this source.

Other anti-drug, government-endorsed plots were as subtle as a brick through a window. "Chicago Hope" is owned in part by News Corp. subsidiary 20th Century Fox Television. Though CBS was the potential beneficiary of any ONDCP-approved "Chicago Hope" episode, an agreeable News Corp. exec, Mark Stroman, phoned John Tinker, an executive producer on "Chicago Hope," to request an anti-drug episode. Facing cancellation and commanding scant leverage with the show's owners, the "Chicago Hope" producers dusted off a previously rejected script and decided it could stand another rewrite.

As broadcast, the graphically anti-drug story of the tragedies afflicting young post-rave revelers featured drug-induced death, rape, psychosis, a nasty two-car wreck, a broken nose and a doctor's threat to skip life-saving surgery unless the patient agreed to an incriminating urine test -- along with a canceled flight on the space shuttle.

Other drug office-approved shows featured: a career-devastating, pot-induced freakout of angel-dust proportions ("The Wayans Bros."); blanket drug tests at work ("The Drew Carey Show") and for a school basketball team (NBC's Saturday morning "Hang Time"); death behind the wheel due to alcohol and pot combined ("Sports Night"); kids caught with marijuana or alcohol pressed to name their supplier ("Cosby" and "Smart Guy"); and a young teen becoming an undercover police drug informant after a minister, during formal counseling, tells his parents he should ("7th Heaven").

At least one show, "Buffy the Vampire Slayer," was rejected after it showed itself to be immune to the drug office's worldview. "Drugs were an issue, but it wasn't on-strategy. It was otherworldly nonsense, very abstract and not like real-life kids taking drugs. Viewers wouldn't make the link to our message," says someone in the drug-policy office camp who read and helped reject it.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Levitt, the office's point man on the campaign, downplays the money's influence on the networks' "voluntary" creative decisions. He likens the process to the (non-monetary) Prism Awards for socially responsible television. "The government is not dictating these kinds of changes," he says. "We will provide an incentive, a financial incentive."

Levitt insists that his office is trying solely to achieve accurate portrayals of drugs -- not any overall increase in the number of anti-drug episodes broadcast. Be that as it may, by the office's own count, the number of shows with anti-drug themes (whether financially boosted by the office or not) has risen from 32 as of last March to 109 this winter.

Whatever the intent of the government program, it was deemed sensitive enough to be kept under wraps. The TV producers typically knew nothing of the money involved. Says Levitt, "In almost every instance that I'm aware of, the [creative] people coming to us have no understanding at all of the pro bono match. They have no idea." Asked if they should know of the financial arrangement, Levitt says no: "We're not trying to intrude on their creative freedom. If the perception is such that we are trying to influence the [TV] program financially -- well, I won't go any further."

This reporter spoke with some 20 writers, producers and production executives for major shows. With perhaps one exception, nobody knew of the arrangement.

John Tinker, last season's "Chicago Hope" executive producer, took the News Corp. call requesting an anti-drug episode. He recalls no mention of CBS being able to recoup something like half a million dollars in ad time for the one shrill episode he helped craft at the show owner's request. He says the financial incentives are "complete news to me." He adds, "I'm so caught off guard, so stunned. I like to think I'm well informed. I had not a clue about any financial incentives." Asked if the scheme gave him cause for concern, Tinker says, "Of course. It smells manipulative ... All of this is disturbing."

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Tinker's response would undoubtedly be shared by many in Hollywood's creative community. One network sales executive who's worked with the drug-policy office acknowledges that if producers were to learn that scripts were being altered, that would "start a nightmare." This executive adds, "I don't need it getting back to [a particular powerhouse producer]. I'm in a tough situation between the client and the shows."

Realizing how tough it might get, a lot of top brass shied from trumpeting their enlistment in the drug war. In a brief conversation, Rosalyn Weinman, NBC's executive vice president for content policy and East Coast entertainment, said that the drug office did not exercise "script approval," but conceded that there had been conversations about broad issues or "specific concerns." Other NBC officials declined comment. Two other NBC executives implicitly confirmed the deals, however.

Senior management and public relations officials at each of the other four networks involved last season -- ABC, CBS, the WB and Fox -- were contacted, but offered little in the way of substantive comment.

While no current Fox executive would comment on the network's cooperation with the government, Rob Dwek, the network's former executive vice president of comedy and drama series, maintained that the financial incentives have "no impact on what we do creatively -- it would have no effect on the direction of a show ... It's not noticeable, it doesn't hurt the quality of our product, and it allows us to be responsible."

An ABC public relations exec, speaking anonymously, confirmed the network's participation in the deal. "Halfway through the year ['98-'99 season], ONDCP said we can meet the match ... if programming was appropriate. I don't know the month. But it was after setting up the [matching ads] schedule."

CBS president Leslie Moonves had nothing to say. A CBS spokesman said simply, "CBS is proud to be working with the government in regard to the war on drugs."

Michael Mandelker, executive VP of network sales for UPN, sounded enthusiastic about the program. Speaking this summer, he said he'd "already started a dialog with programming. Somewhere there will be shows that qualify."

Mandelker said he urged UPN entertainment president Tom Nunan to drum up support for anti-drug messages with producers, asking him: "Is there a way to have these kinds of story lines as you talk to producers?" Mandelker adds, "I imagine ONDCP will look at a couple of scripts in the first year to make sure our interpretation is theirs." He stated further, referring to UPN's strategy: "Tom approaches the producers. We [sales] can't do anything for them. Tom can pick up a show."

Time Warner CEO Gerald Levin, vice chairman Ted Turner and the WB head office all declined comment.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

The drug office's campaign is only just approaching full flower.

The teen-friendly WB (home to "7th Heaven" and the since-cancelled "The Wayans Bros.") has, for example, "significantly" expanded its anti-drug messages, one insider notes, with the drug office more than doubling its WB buy this season. The WB had initial plans for "at least five" programs with anti-drug content counting as a match, the source adds.

"Last year was the program's first year," he points out, "and a lot of companies didn't understand the match." He predicts the practice will only increase as the networks come to understand it as an effective way to free up valuable ad time otherwise sold at half-price.

Shares