"You can't break/The ties that bind" -- Bruce Springsteen

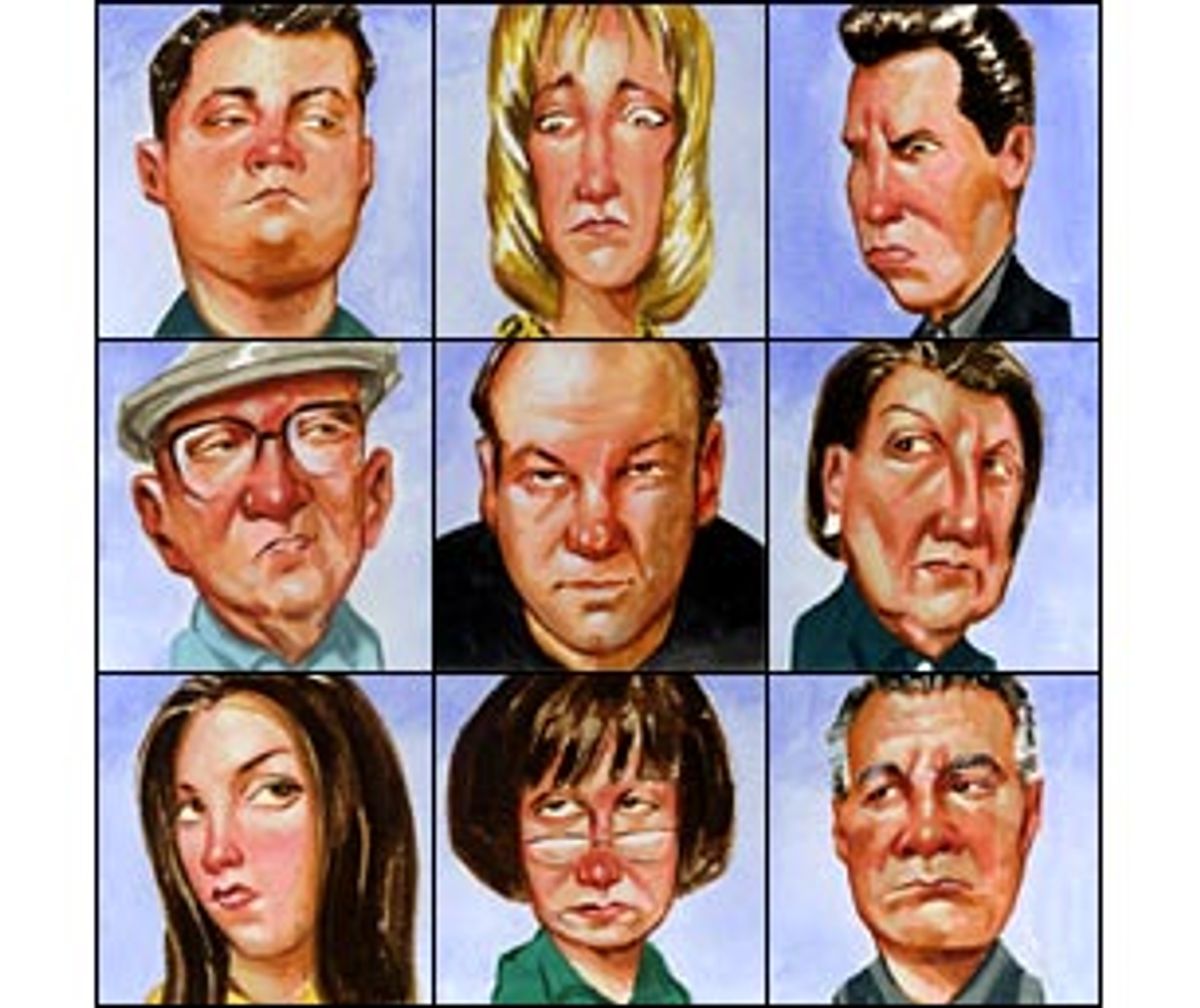

When we last saw New Jersey Mafioso Tony Soprano (James Gandolfini), he and his wife Carmela (Edie Falco) and teenagers Meadow (Jamie Lynn Sigler) and A.J. (Robert Iler) were huddled around a table at the red-sauce Italian restaurant run by Tony's boyhood pal Artie (John Ventimiglia), taking refuge from a howling rainstorm and a power failure. In the candlelight, with thunder cracking and tree limbs groaning outside, Tony raised his glass of vino and proposed a toast to his family. "Someday soon, you're gonna have families of your own," he told his kids. "And if you're lucky, you'll remember the little moments like this, that were good."

That scene was an almost absurdly peaceful ending to the dark comedy-drama's explosively entertaining first season: Didn't the anxiety-riddled, Prozac-popping Tony just survive a hit suggested by his own mother (she was enraged at him for putting her in a "retirement community"), and wasn't he just barreling down the retirement home corridor, pillow in hand, intent on suffocating the mean-spirited old bat? (Instead, he found her surrounded by emergency medical personnel -- she'd suffered a stroke.)

But while the season-ending closeness of Tony and his immediate family may have been ironic (after all, he's a cheating husband who's also a murderer and a racketeer, Carmela is fed up with him and the kids are sullen manipulators), it was no illusion. Vendettas, grudges and betrayals come with the territory of family, but Tony's right, you have to remember the good times. The Sopranos are no more dysfunctional than any other upper-middle-class suburban brood, and in one enviable way, they may be less dysfunctional -- at least this family sits down to eat dinner together every night. And that goes for Tony's work family too; Tony and Paulie and Pussy and Silvio may bicker and squabble, but when the capicolla and the salsicce come out, that time is sacred. If we learned one thing from the first season of "The Sopranos," it's this: A family is a family, whether you're born into it or you take an oath to join it. And nobody gets out of a family alive.

In the much anticipated second season of "The Sopranos" (which opens Jan. 16 on HBO), the show's main concern is still family ties and the secrets that cement them: the secrets parents keep from children, children keep from parents, spouses keep from spouses, friends keep from friends, families keep from the community, mobsters keep from rivals. For the uninitiated, the two most potentially lethal secrets at the heart of the show are Tony's visits to a psychiatrist for his panic attacks (old-school Mafiosos consider talking to a shrink a betrayal of family business), and the mode of oral sex favored by Tony's uncle Corrado "Junior" Soprano (Dominic Chianese), which is considered a sign of male weakness in mob culture and which Tony teased him mercilessly and recklessly about when Junior's girlfriend let it slip. "Cunnilingus and psychiatry brought us to this," Tony mused philosophically as last season neared its climax of family/Family vengeance and wounded tough-guy pride.

Much of Tony's world involves saving face, preserving the outward appearance of power and manliness. And he labors so hard at it that you can't help but sympathize with and root for him. Yeah, he's a killer, but he's got midlife agita anyone can relate to -- he's growing apart from his wife, he's feeling middle-manager job pressures, he's sandwiched between caring for his difficult elderly mother and providing for his college-bound teens. Here is a man whose professional and personal lives are bound by the omert`, the code of silence, and he's in psychotherapy, for cryin' out loud, where there are no secrets. What a delectably wry fix "Sopranos" creator David Chase has dreamed up for his hero.

As fans know, most of Tony's problems, psychological and otherwise, trace back to his overly dramatic, poisonously joyless mother, Livia (Nancy Marchand). In a neat twist on the usual patriarchal Mafia stories, "The Sopranos" is about the sins of the mother visited on the son; the show has a deep understanding of the towering psychological power mothers wield over their children. As the second season opens, Livia is still in the hospital going through rehab, although her "stroke" was psychosomatic, brought on by "repressed rage" at Tony surviving the hit. (In an unsettling mingling of art and life, Marchand herself is fighting lung cancer and chronic pulmonary disease, so when you see Livia with oxygen tubes up her nose, you wonder if they're props or the real thing.)

But even in her weakened, addled state, Livia still looms larger than life in Tony's psyche. "She's dead to me," Tony announces about a half-dozen times in the first three episodes of the new season, and the way he dwells on it tells you that she isn't and can never be. But that's the bitch about families: To paraphrase Steve Van Zandt's Pacino-wannabe Silvio, just when you think you're out, they pull you back in.

This season, Tony's family problems are compounded by the sudden arrival of his older sister, Janice (new cast member Aida Turturro), who has been living on the West Coast for 20 years, putting a continent between her and the old lady. Janice, who has taken the Hindu name Parvati, is a pot-smoking, Birkenstock-wearing, free-spirited con artist. She tells Tony that she's come back home to assume her share of the caretaking burden, but Tony suspects that she's out for a piece of the inheritance if Livia kicks. Watching Janice struggle to keep her temper and play the part of the loving, serene daughter while Livia pushes her buttons, it's hard not to see things Tony's way. This could turn out to be a fight to the death for the female power in the family.

And Turturro insinuates herself wonderfully into the mix; Janice and Tony get on each other's nerves with pitch-perfect sibling antagonism. When Meadow (who is all attitude this season, and quite taken with her boho aunt) gets caught throwing a party in Livia's old vacant house, Janice offers Tony and Carmela some spiritually enlightened parenting advice: "There's a Zuni saying: 'For every 20 wrongs a child does, ignore 19.'" To which Tony responds with a sneer, "There's an old Italian saying: 'You fuck up once, you lose two teeth.'"

Meanwhile, on the business side, Tony has been elevated to street boss by Junior's incarceration, but he's being forced to devise more and more scams to throw the Feds off his scent. In one of these diversification moves, Tony takes over a brokerage firm, installs cokehead/aspiring screenwriter Christopher Moltisanti (Michael Imperioli) as "SEC compliance officer," and uses it to launder money through the stock market. Then there's the problem of Pussy Bompensiero (Vincent Pastore), the Soprano soldier whom Tony erroneously figured for a government rat. Pussy went on the lam, but now he resurfaces with a story about being in a Puerto Rican clinic for a bad back. While his story checks out, Tony can't shake his suspicions about the man he affectionately calls "beached whale."

In the Jan. 23 episode, Tony gets a new headache in the form of Richie Aprile (David Proval), the older brother of deceased capo Jackie Aprile. Richie, who has just gotten out of prison after 10 years, wants his rightful share of the action, which he feels Tony has usurped. The yoga-practicing, grudge-carrying, possibly pyscho Richie chafes at taking orders from Tony. He's positioning himself as a threat and, to make matters worse, he's doing it from the inside: He used to date Janice, and the two may be getting close again.

But the really bad news for Tony is that he has to face all of these crises without the services of his shrink, Dr. Jennifer Melfi (Lorraine Bracco), who is hopping mad at him for making her go on the lam after the attempt on his life (he feared that she might be targeted for knowing too much). The estrangement is taking a toll on both patient and doctor. Tony is suffering from anxiety attacks again (he has one while he's behind the wheel, apparently brought on by listening to "Smoke on the Water"), so he goes to see another shrink, but the doctor refuses to take him on as a patient ("I've seen 'Analyze This' -- I don't need the ramifications").

As for Melfi, she's secretly seeing patients in a roadside motel room (a sly allusion to Tony's boorish equation of her services with those of a prostitute last season). But she's also having troubling dreams about Tony and his well-being, and her conflicted feelings send her to her own shrink (played by film director Peter Bogdanovich), who suggests that she's attracted to him -- something we've known since the episode last season where she defended Tony a little too fiercely to her ex-husband when he dismissed Tony and his ilk as a stain on the reputation of all Italian-Americans.

That Melfi, an upstanding Italian-American and feminist, finds herself caught up in the pull of Tony's retro charm is one of the show's most audacious flourishes. Melfi is the audience's surrogate and her fascination with Tony is a metaphor for our own fascination with the Mafia, particularly as it's been depicted onscreen in "The Godfather" trilogy, "Mean Streets" and "GoodFellas." There's something about those colorful gangsters, with their swagger and their loyalties and their (perceived) victimless crimes, that reels audiences in, again and again.

And Melfi isn't the only civilian who's smitten; "The Sopranos" is filled with mob groupies, from Tony's mild-mannered neighbor, Dr. Cusamano (Robert Lupone), who shows off Tony to his golfing buddies (Tony refers to him behind his back as a "Wonder Bread Wop"), to Melfi's family counselor, who listens to Melfi and her ex's angry exchange about her having a gangster as a patient, and then proudly offers his own bit of family history -- he had a relative who ran with mobster Louis Lepke ("That was one tough Jew"). Chase's best joke, though, is that even the guys in Tony's crew look to the movies, "The Godfather" in particular, for a whiff of the lost machismo and glamour of La Cosa Nostra, which has been weakened from without by federal RICO statutes and from within by impatient young Turks like Christopher, who see the mob as a quick career path to Hollywood.

But even when you take the Mafia out of the equation, the Italian seasonings of "The Sopranos" are utterly irresistible, beginning with the ethnic pride and underdog scrappiness these characters still carry with them on their hejira to upper-middle-class respectability. "Do you know who invented the telephone? An Italian, Antonio Meucci," Tony tells his son. "He was robbed!" And then there's the food -- my God, the food! I mean, doesn't your mouth water when Carmela takes another steaming dish of baked rigatoni out of the oven, or Tony twirls his spaghetti around a meatball as big as his fist?

And, of course, there's Francis Albert. At the beginning of the Jan. 16 episode, a breathtaking montage illustrates the ebb and flow of Soprano life since last season, and it's choreographed, gorgeously, to Sinatra's "It Was a Very Good Year." The scenes float into one another as if you're flipping dreamily through an uncensored family album: Tony playing solitaire, banging his mistress, giving Meadow a driving lesson; Junior behind bars; Livia in her hospital bed; Carmela serving up dinner; Christopher snorting coke while an Edward G. Robinson movie plays on TV. Sinatra's melancholy paean to virility past and good times slipping away is so dead-perfect as a "Sopranos" anthem, the Chairman of the Board could be singing about each character, as each character -- the same way Bruce Springsteen could have been the unsteady inner voice of Tony Soprano when he whispered his disquieting "State Trooper" ("License, registration, I ain't got none/But I got a clear conscience 'bout the things that I done/Mister state trooper, please don't stop me") over the closing credits of last season's final episode.

You don't have to be Italian to feel like one of la famiglia watching "The Godfather," or to share Francis Albert's romantic mood swings. And you don't have to be from the Garden State to feel the Jersey in your soul when you're at a Springsteen concert watching the Boss and the E Street Band doing "Born to Run" or "Backstreets" or "Atlantic City," songs that hover unsung over every lovingly photographed street scene of "The Sopranos" (David Chase is a Jersey boy, too). And so it is with "The Sopranos." Sure, the show's astonishing popularity owes a lot to its crackerjack storytelling and uncompromised vision. But, like Sinatra, Springsteen and "The Godfather" before it, the show also opens up, generously and vividly, a particular set of experiences (being Italian, growing up blue-collar in New Jersey) for the rest of us, and turns them into shared pop cultural history.

"The Sopranos" woos third and fourth generation Americans -- grown beyond our ancestors' ethnic identities, hometown loyalties and economic classes -- with what we crave most: roots. You watch "The Sopranos" and it stirs some deep-down tribal memory. You feel like you know this family, these people with their big emotions and their messy relationships and their ties that bind, and in some strange way, you feel like you're home.

Shares