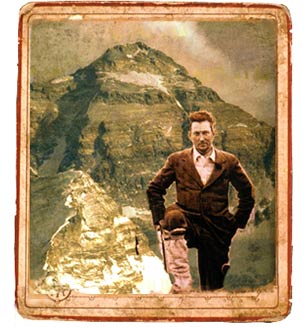

The fact that Sir Edmund Hillary and Sherpa Tenzing Norgay were the first to reach the summit of Mount Everest, the worlds highest mountain, on May 29, 1953, has always carried with it a nagging footnote. Twenty-nine years earlier, two English climbers, George Leigh Mallory and his partner Andrew Comyn Irvine, disappeared into the mists as they pushed toward the summit. This was the same George Mallory who gave the 20th century one of its pithiest sound bites, an irreducible koan that, however it was intended, has come down to us as the classic defense of reckless endeavor. Asked by a pestering journalist why anyone would want to climb Everest, Mallory is said to have shot back, “Because its there.”

For climbers and historians, the question has always remained: Did one or both of the climbers make the top before they died? As they made their own way toward the mountains upper reaches last spring, the climbers of the Mallory/Irvine Research Expedition debated the question among themselves. Most of the crew were arguing on the doubtful side. The route up the Northeast Ridge, they contended, would simply have been too difficult in 1924.

The expedition, led by experienced Himalayan guide Eric Simonson, was the brainchild of a young German Everest historian named Jochen Hemmleb. Working from scant clues, the mostly American team hoped to find an old “English dead” reportedly seen by a Chinese climber in 1975. The body was generally thought to be that of Andrew Irvine, who, it was hoped, was carrying a Kodak Vestpocket camera Mallory had borrowed for the attempt. If the camera contained shots from the summit, the mystery could at last be laid to rest.

As it happened, the headline-generating discovery the team made, on May 1, 1999, was mostly a product of chance and intuition rather than scientific deduction. The climbers lucked into perfect weather for the search: It had been a dry year in the Himalayas and the mountain was practically scoured clear of snow. And it was only in following his own instincts and wandering far outside the established search zone that climber Conrad Anker stumbled upon a trail of broken bodies that led him to the corpse — which turned out, spectacularly enough, to be Mallory’s, not Irvine’s. Eerily preserved at nearly 27,000 feet on the mountains North Face, the body was bleached and frozen to the rocky slope, the fingers dug desperately into the rubble.

No camera was found, but the body did yield a few clues. Mallory had died in a fall, although not a long one. In the end, he appears to have been roped to Irvine. As much as anything, the discovery had what climber Anker would later call a “galvanic effect” on the teams judgment. Opinion now swung strongly in favor of the idea that Mallory had in fact made it. Three days after the historic find, Anker himself was telling NOVA producer Liesl Clark, “After seeing George up there, I now think he may have reached the summit before he fell.” But by the time the expedition was wrapping up — after Anker and teammate Dave Hahn had reached the summit themselves — his assessment had come 180 degrees again.

That change of opinion has subsequently become a point of bitter controversy among erstwhile teammates. Accusations and recriminations have come on the heels of two competing, and at times contradictory, accounts of the expedition: “The Lost Explorer,” by Conrad Anker and David Roberts, and “Ghosts of Everest,” the “exclusive team story” by Jochen Hemmleb, Eric Simonson and mountaineering publisher Larry Johnson, as told to ghostwriter William Nothdurft.

Most notably, the two books differ sharply in their conclusions about what might have happened on that fateful day in 1924. Where Anker and Roberts remain skeptical, “Ghosts of Everest” argues strenuously that Mallory and Irvine could have made it. In the process, critics charge, its authors have played fast and loose with a hallowed piece of mountaineering history.

“So much depends on Odell’s sighting,” Walt Unsworth laments in his 1981 book “Everest.” Indeed, even after Mallory has been found, the famous last sighting of Mallory and Irvine is still the only evidence to place them on the final stretch to the summit.

Geologizing at 26,000 feet, 1924 expedition member Noel Odell looked up from a crag he had climbed to see “the entire summit ridge and final peak of Everest … unveiled.” According to a report in the Times of London on July 5, 1924, Odell said, “My eyes became fixed on one tiny black spot silhouetted on a small snowcrest beneath a rock-step on the ridge, and the black spot moved up the snow to join the other on the crest. The first then approached the great rock-step and shortly emerged at the top; the second did likewise. Then the whole fascinating vision vanished, enveloped in cloud once more.” It had to have been Mallory and Irvine, less than a thousand feet from their goal.

But where exactly did Odell see them? Certainly he placed them on the ridgeline, but on what part of it? A series of three rock outcroppings called “steps” divide the ridge. While Odell went to his grave insisting he had seen them at the First Step, his initial accounts suggested they were higher: “Nearing base of final pyramide [sic]” was how he put it in his journal. The authors of “Ghosts of Everest” choose to believe his first accounts, arguing that he revised his story only after being pressured to do so by skeptics and naysayers. Furthermore, they argue, his initial account rules out the First Step. Mallory and Irvine, they conclude, must have been at the Second or the Third Step, much closer to the summit.

The question then becomes: Could Mallory and Irvine have climbed the Second Step, which at 90 feet, rises up off the ridge like the prow of a freighter? Since 1975, all climbers coming along this route have availed themselves of a Chinese ladder affixed to the rock with pitons — and many have doubted whether it could ever have been free-climbed. Brought along on the expedition as a kind of one-man Kon Tiki, Conrad Anker — an accomplished technical climber with no Everest experience — was there primarily to answer that question and to rate its difficulty.

On May 17, 1999, 16 days after finding Mallory, Anker and his climbing partner, Dave Hahn, reached the foot of the Second Step. Four other climbers from the summit party — two Americans and two Sherpas — had already turned around that day. Hahn, who had been commissioned to film the critical ascent for NOVA and BBC documentaries, was instead forced to belay his teammate; on the exposed route up the Second Step, an unprotected fall would spell certain death in the form of a 7,000-foot tumble down the North Face. As a result, both documentaries about the expedition — the NOVA film “Lost on Everest” premieres Jan. 18 — contain no footage of the controversial attempt.

The details of what exactly happened on the Second Step that day are not only fuzzy but also somewhat unsatisfying — which is to say that Anker almost free-climbed the Step, but not quite. As he explained when he radioed down from the top of the Second Step to Advanced Base Camp: “I got a hand jam into the crack … and then I had to step out. At that point the ladder was in the way. I had some edges in there, but I think due to the fact that I’m weak, more than anything, I stepped on the ladder.”

However, on MountainZone.com, which was cyber-casting reports on the expedition’s progress from the mountain, Eric Simonson posted a brief dispatch stating that “ultimately Conrad was successful in free climbing the Second Step.”

For Anker, this was tantamount to lying, and when he found out about it on his return to Advanced Base Camp, he was furious. “I feel he misrepresented me right off the bat … And I came down and I had a cow with him,” he told me last November. “I said, ‘This is bullshit. You know, I’m going to have to retract this’ … Look at the interview I did in Climbing — I was really point blank: I said, hey, I want everybody to know I stepped on the ladder … I didn’t do it, because I’m not strong enough.”

“That’s not what he said at the time,” Simonson countered when I interviewed him on the phone from his home in Ashford, Wash. “The way Conrad described it afterwards was that the ladder was in his way and he was trying to stand on a foothold, but the foothold was right behind the ladder. And he ended up putting his foot on the ladder for one step. But I mean, I give Conrad credit for having climbed the thing … As far as I’m concerned, he climbed it.”

There is also some confusion about Anker’s assessment of the Second Step. Immediately after having climbed it, on the same call to Advance Base Camp, Simonson asked him: “How hard is it and do you think George could have done it?”

Anker answered: “It’s probably 5.8 at normal elevation, but it feels like 5.10 up here.” To the second half of the question, he seems to answer in the affirmative: “He probably just would have knee-barred up the off-width and then pulled over. It’s not that long but it certainly winds you up here.”

Writing in his book “The Lost Explorer,” Anker revised his rating upward, however. “The Second Step is probably a solid 5.10. And that’s a lot harder than anything climbers were doing in plimsoll shoes, hemp ropes, no pitons, and a ‘gentleman’s belay’ (with no anchor to the rock) in the early 1920s.”

“Again, that’s not what he said at the time,” Simonson told me. “In fact, [at the time] he says it would have been possible but difficult. And so I can only go by Conrad’s own words to the extent that he has apparently kind of changed his story afterwards and now says that he thinks it would have been impossible … It’s kind of interesting — if you’re a student of Everest history, you’ll recall how Noel Odell changed his story after he got back in 1924. Noel Odell in his diary excerpts and in his original comments about his sighting was fairly unequivocal and then later, after he got back and was subjected to so many people badgering him, he started waffling and changing his story. So I kind of call it the Noel Odell Syndrome.”

Jochen Hemmleb, too, thinks Anker has changed his story since climbing the Second Step and giving it a rating of 5.8, a level of difficulty he thinks was within Mallory’s range. (David Breashears, who commissioned modern climbers to retrace some of the old climber’s best routes in Wales, says 5.8 would have been at the high end of Mallory’s abilities at sea level.)

Liesl Clark, the NOVA producer who was also posting dispatches on the Internet during the expedition, believes the confusion is a matter of semantics. “Eric did not ask Conrad, Do you think he did it? He asks, Do you think he could have done it? So, it’s kind of stupid, but I have to say that three days later then, down at Base Camp … I then, on camera, asked Conrad Anker, Do you think he did make it? Here is his direct quote: ‘Much as I wish I could just say, George and Sandy, you climbed Everest — Chomolungma, the highest peak in the world — you were the first ones to do it, I find that, given the severity and technical requirements of this route and the standard of climbing in 1924, I find it improbable.'” Clark’s documentary concludes with this pronouncement.

In subsequent interviews, Anker has been unwavering in his verdict.

Simonson, on the other hand, would himself seem somewhat guilty of changing his tune. In Katmandu after the expedition, he told the assembled press, as reported by Reuters on May 25, “I don’t think they made it to the summit. The route was too long and too hard.”

The truth of an expedition may be a hard thing to come by, especially the truth of an Everest expedition. It has something to do with what Jon Krakauer has called “the stunning unreliability of the human mind at altitude.” What’s more, there is the simple matter of differing perspectives, faulty memories, iffy interpretations — which is to say, the usual limitations on human knowledge. And yet precisely because we are human, we strive to know the truth. In the case of Mallory and Irvine, we want to know what happened to them, to settle the mystery, and so we are impatient with inconclusive evidence, with incomplete reports and inconsistencies. Ultimately, we attempt to clear up the picture wherever possible, to bring things into focus. In our thirst for resolution, however, it is too easy to ignore the inherent and inconvenient complexities.

“When unraveling mysteries,” the penultimate chapter of “Ghosts of Everest” begins, “it is wise to remember something Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes once said: ‘When you have eliminated everything that cannot be, whatever remains, no matter how improbable, is what must be.'”

The brand of reasoning employed in “Ghosts of Everest,” however, is not so much deductive as reductive. It pretends on more than one occasion to address all the possibilities in a given scenario when in fact it ignores most real ones and erects easily defeated straw men instead. As to the question of why Mallory’s sun goggles were in his pocket, for example, the authors of “Ghosts of Everest” argue, “There are only two possible conclusions: Either Mallory was stupid, which he manifestly was not, or he and Irvine did not return when their second bottles ran out.” Otherwise, the reasoning goes, they would have been descending in daylight, in which case the goggles would have been on. Really, what the authors are saying is that there is only one possible conclusion.

But in a review published in the New York Times last November, climber and filmmaker David Breashears, co-author of a book on the early English Everest expeditions called “The Last Climb,” offered writer Christopher Wren three other possibilities off the top of his head, all of which seem plausible. The goggles might have gotten clogged with snow, Breashears suggested, or Mallory might have removed them to climb in shadow, or he might have carried a spare set, because the expedition’s acting leader, Edward F. Norton, had been immobilized with snow blindness a few days earlier. The authors of “Ghosts of Everest,” however, do not see fit to address any of these likelihoods. In their estimation, there are only two options: Mallory was stupid or they were descending in the dark.

Another focus of the book is the question of oxygen. Sleuthing through the notes found on Mallory’s body, Hemmleb arrived at a compelling theory, based on an inventory scratched on the back of an envelope, that Mallory and Irvine had the potential to carry three bottles of oxygen each on summit day — enough to get them to the top.

Here too, however, the logic is somewhat tortured and all inconvenient evidence dismissed. In a note Mallory sent down from Camp VI to Odell at Camp V, he said they would “probably go on two cylinders” to the summit. To Hemmleb, et al., the word choice is meaningful. “Note that Mallory did not write, ‘… we’ll have to go on two cylinders.’ By using the word ‘probably,’ Mallory signaled he had a choice, and the only way he can have a choice is if he had at least six full or nearly full cylinders … Mallory was a writer of significant talent,” the authors conclude suggestively. “He used words with precision.”

A fuller quote from Mallory’s note gives a distinctly different impression of his intentions. “To here on 90 atmospheres for the two days,” he wrote, “so we’ll probably go on two cylinders — but it’s a bloody load for climbing.”

As for the precision of his words, it is worth noting that in another note Mallory sent down from high camp that day, he confused 8 a.m. with 8 p.m.

Moreover, couldn’t the word “probably” suggest another choice — that between two cylinders and one? The question is not addressed.

In this fashion the reader is drawn along, as the authors argue their protagonists upward. That they wish so badly to put them on the summit may simply be a matter of innocent yearning. But at least a couple of critics see it as a calculated attempt to make money by selling people what they want to hear. One of those critics is Anker’s coauthor, David Roberts, who roundly dismisses what he calls Hemmleb’s “overdetermined mad science” and “shadowy pseudo-facts.” Another is Reinhold Messner, arguably the greatest mountaineer of all time. At last year’s Frankfurt Book Fair, the legendary Tyrolian publicly accused the young historian of falsifying the truth in order to cash in. To Conrad Anker, he sent a fax that ended simply: “Hemmleb is telling a great nonsense.”

If all the back-and-forth seems hopelessly petty, a mere pissing match, it is important to remember that mountaineering, more than most sports, is intimately tied to its history, and the record of first ascents is held as sacrosanct. Indeed, the first ascent of the world’s highest mountain is nothing less than a grail. In struggling to coax their Galahad to the Siege Perilous, the authors of “Ghosts of Everest” have understandably angered the climbing establishment.

In a sense, the discovery of Mallory’s body did nothing to solve the mystery. The fact remains that there is no physical evidence to place him or Irvine above the Second Step. And while Conrad Anker maintains they could not have climbed it, he and Roberts offer another test that is even more strenuous. Could they have climbed down it?

We know that Mallory and Irvine did not fall from the Second Step. Had they, they would have plummeted 7,000 feet to the Rongbuk Glacier. Mallory’s body was found in a catchment basin far to the north of the Second Step and most observers agree that he fell from well below the ridge, in a section of crumbly limestone called the Yellow Band. If we wish to believe that Mallory and Irvine made it above the Second Step, and thus past the last significant hurdle before the summit, we also have to get them back down it.

Any mountaineer can tell you that climbing down is many times harder than climbing up. On the descent of the Northeast Ridge, modern climbers simply rappel the Second Step along fixed ropes. But Mallory and Irvine had no way to anchor a rope to the rock.

In “Ghosts of Everest,” this problem is sidestepped. In the midst of a discussion about the timing on summit day, the question is posed as follows:

Could they have climbed down the Second Step in the dark? Everest veterans, including Eric Simonson, say it is impossible. But of course we know Mallory (and presumably Irvine as well) did climb down the Second Step successfully; his body was found below the Yellow Band, north of the First Step, not the Second. If it is impossible to climb down the Second Step in the dark, then the only conclusion is that they climbed down the Second Step in daylight or dusk.

As to how they managed that feat, the book is mute.

In fact, Eric Simonson is on record as saying he doesn’t think the Second Step can be down-climbed at all. “I think getting down the Second Step remains a huge issue,” he told a Scripps Howard News Service reporter after the book had come out. “I don’t think they could have climbed down it. They would have had to rappel down. And they certainly didn’t leave their rope up there. Nobody’s ever found any piece of rope dangling from a rock up there.”

It would seem that the authors of “Ghosts of Everest” are thus internally inconsistent and their argument undermined. If Mallory and Irvine couldn’t have down-climbed the Second Step, then quite plainly they never got above it. And if they never got above it, they did not summit — at least not by the ridge route.

I should hasten to add “probably” to that last sentence. They probably did not summit. Unless the camera is found showing the view from the summit, we may never know for certain whether Mallory and Irvine reached the top. While the weight of the evidence would suggest they did not, it seems wise to allow for small miracles. And in the final analysis, it is miraculous that they made it anywhere near where they did. For now, we will have to salute them for that.