The vast majority of Americans probably don't want to think about the Clinton crisis ever again. Even the most lubricious revelers in the affair -- and who can claim to have endured this endless political snuff movie without doing a little furtive wallowing? -- must by now be suffering from a monumental case of post-unconsummated-oral-sex tristesse. We're sick of the media frenzy, sick of the culture war, sick of the breast-beating analysis. The whole sordid episode already seems, mercifully, never to have happened. Why on earth would anyone want to relive the ugliest one-night stand in American political history?

But before tuning the whole thing permanently out, it's worth remembering that a little over a year ago the nation saw what should have been merely an embarrassing episode in the career of a randy politician turned into a constitutional crisis. The Clinton affair was a bedroom farce that could have ended as tragedy. In all probability, only a harried prosecutor's badly worded definition of "sex" prevented an American president from being removed from office for the crime of lying under oath about a consensual sexual affair. Instead of amusing ourselves with ever more gargantuan corporate copulations, we could be in a toxic civil landscape, the tanks of triumphant Limbaughism rumbling against an army of bitter, morally relativist boomers. Which is why it's important, now that partisan passions have cooled, to look at exactly how and why this gigantic mess landed in our laps.

Jeffrey Toobin's "A Vast Conspiracy" is a lucid, level-headed and ultimately convincing recounting, from a largely legal perspective, of what is sure to be regarded by future historians as one of the weirdest and unloveliest episodes in American history. Toobin is the legal expert at the New Yorker and ABC News, and his expertise helps him to blow the hysterical smoke out of the room and recount exactly what happened. This in itself is a valuable service, because the Clinton crisis is one of those murky stories whose true (and frightening) absurdity only becomes clear when it is anatomized.

The title of Toobin's book is taken, of course, from Hillary Clinton's famous statement on the "Today" show that "the great story here ... is this vast right-wing conspiracy that has been conspiring against my husband since the day he announced for president." Toobin, who is no Clinton apologist, points out that her statement ignored her husband's culpability, that many of the "conspirators" didn't know each other and that when she made her statement there was no evidence that any of them had broken the law. And indeed, he finds little evidence of illegal activity throughout the affair. Nonetheless, he believes that her "charge had -- and has -- the unmistakable ring of truth. The Paula Jones and Whitewater investigations existed only because of the efforts of Clinton's right-wing political enemies. People who hated the Clintons initiated these projects and sustained them through many years. To put it another way, there was no one of importance behind either the Starr investigation or the Paula Jones case who was not already a dedicated political adversary of the Clintons."

The story, in short, is of how a host of ideologues, zealots, ax-grinding hustlers, professional Clinton-haters and useful journalists connived to keep not one, but two flimsy legal cases against the president of the United States alive until, in a dramatic climax out of Aeschylus by way of Larry Flynt, the protagonist's tragic inability to keep his pants up almost brought him down.

Unfortunately, Toobin scarcely mentions a major element in the "vast conspiracy," the covert operations funded by far-right Pittsburgh billionaire Richard Mellon Scaife. Nor does he give readers much of a sense of the bizarre texture, the strange commingling of deep-fried kooks and respectable establishment figures, that made up the anti-Clinton forces. Readers who want to plunge into that seamy soup should turn to Joe Conason and Gene Lyons' forthcoming book, "The Hunting of the President," which makes an excellent complementary volume to Toobin's. (Conason is a Salon columnist; both journalists have written extensively about the Clinton crisis in these pages.)

Of the rogues' gallery of characters, Toobin is especially harsh on three: The so-called "elves," the loose alliance of high-powered lawyers and financiers who, driven by hatred of Clinton, secretly lent their expertise to Paula Jones' team and other anti-Clinton groups; independent counsel Kenneth Starr and his team; and journalist Michael Isikoff.

Of two of the main "elves" (the name the secret group gave itself), Richard Porter and Jerome Marcus, Toobin writes, "The issue was not what they did but why they did it ... Most public interest lawyers volunteer for a case because they believe in a cause -- an area of law they want to change. Here, in contrast, Porter, Marcus and their later recruits had no interest or expertise in sexual harassment law. To the extent that they cared at all about the state of the law in this area, they were more sympathetic to defendants than plaintiffs. They joined the cause of this sexual harassment plaintiff [Jones] because their agenda was to try -- in secret -- to damage Bill Clinton's presidency. Their involvement was a classic demonstration of the legal system's takeover of the political system. Indeed, [they] used this lawsuit like a kind of after-the-fact election, to use briefs, subpoenas, and interrogations to undo in secret what the voters had done in the most public of American proceedings."

For Toobin, then, there were not one but two conspiracies: the conspiracy of the elves and other Clinton enemies, and a deeper, structural one -- what he calls "a conspiracy within the legal system to take over the political system of the United States." This pernicious process started, Toobin says, with the best of intentions: the legal activism of Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP, who after World War II were forced to use the courts because racist voter-registration laws ruled out legislative redress. It was initially a favorite tactic of the political left. But inevitably the right, too, discovered legal activism, and embraced "many of the same legal concepts that their adversaries had pioneered -- freedom of speech, equal protection of the laws, and even, eventually, sexual harassment law -- to achieve their aims." And the chief aim of many of the most obsessed conservatives at the end of the century was the removal from office of William Jefferson Clinton.

Toobin makes the obvious point that "Clinton [has] an unusual ability to generate passionate hostility ... Indeed, one cannot understand the long siege of his presidency without weighing the depth and breadth of these emotions." Beyond acknowledging that it was part of a "culture war," however, Toobin does not explore the underlying societal reasons for the virulence of this hatred, confining his analysis to certain cultural and legal developments that allowed that hatred to take tangible shape.

The "partisan rancor on a titanic scale" that convulsed Washington during the Clinton years -- despite the fact that ideologically there was little difference between Clinton and Dole -- was due, he argues, to the influence of two apparently opposing ideologies: feminism and the Christian right. What these movements had in common, he says, was "the idea that the private lives of public people mattered as much as their stands on issues." When this now-morally legitimized obsession with the personal collided with a voracious, competitive news media looking for an excuse to peddle sleaze, the results were predictable. As Toobin sums it up: "And so the forces were arrayed. Politicians shunning policy for cultural warfare. The media using sex to sell. And all of it destined to end up in court."

Toobin probably overstates the influence of feminism's "The personal is the political" on the national agenda -- the logic of anything-goes capitalism (to paraphrase Marx, all that is solid melts into sleaze) was a stronger force, and in any case the media was quite capable of sinking to the bottom all by itself. But he's clearly right about the confluence of social forces that allowed the debacle to occur. And he's dead-on when he argues (as he has in the New Yorker) that it was the advent of an imprudently broad doctrine of sexual harassment that legally unzipped Clinton. In a concise excursus, he shows how federal sexual harassment law (which Clinton helped pass), because it doesn't distinguish between consensual sex in the workplace and actual harassment, empowered Jones' lawyers, and later Starr, to go on a virtually open-ended fishing expedition in search of Clinton's bedmates.

(One hopes that the notorious refusal of some feminist leaders to defend Jones resulted not from a Machiavellian desire to save a "pro-woman" president but from some awareness, however faint, that the well-meaning law they wrought and the sexual behavior of human beings, even when "power imbalances" exist, are not one and the same thing. The same holds for those sputtering CEOs who filled the nation's letters pages with outraged missives asserting, "If I did the same thing Clinton did, I'd be fired." Perhaps they might question whether the law itself might be the problem.)

As Toobin tells his engrossing tale, he throws out juicy tidbits and ogle-worthy quotes unearthed from the case files, as well as some fascinating speculations. Describing Lucianne Goldberg's fascination with the gory details of Clinton's encounters with Monica, he quotes her as saying, "Do you think there's a taping system in the Oval Office? ... The slurping sounds would be deafening." And he quotes someone as saying, after meeting Linda Tripp, "That woman is a fucking cunt. If you want to get in bed with that bitch, you're going to pay for it eventually." This statement would perhaps not be noteworthy, except that the person quoted is one of Starr's prosecutors. As for the speculations, he concludes, for example, that both Clinton and Jones lied about the event that started the whole thing, their infamous encounter in the Excelsior Hotel: Based largely on his assertion that Jones didn't report the incident until some hours after it took place, he argues that a consensual sexual encounter probably occurred.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

-

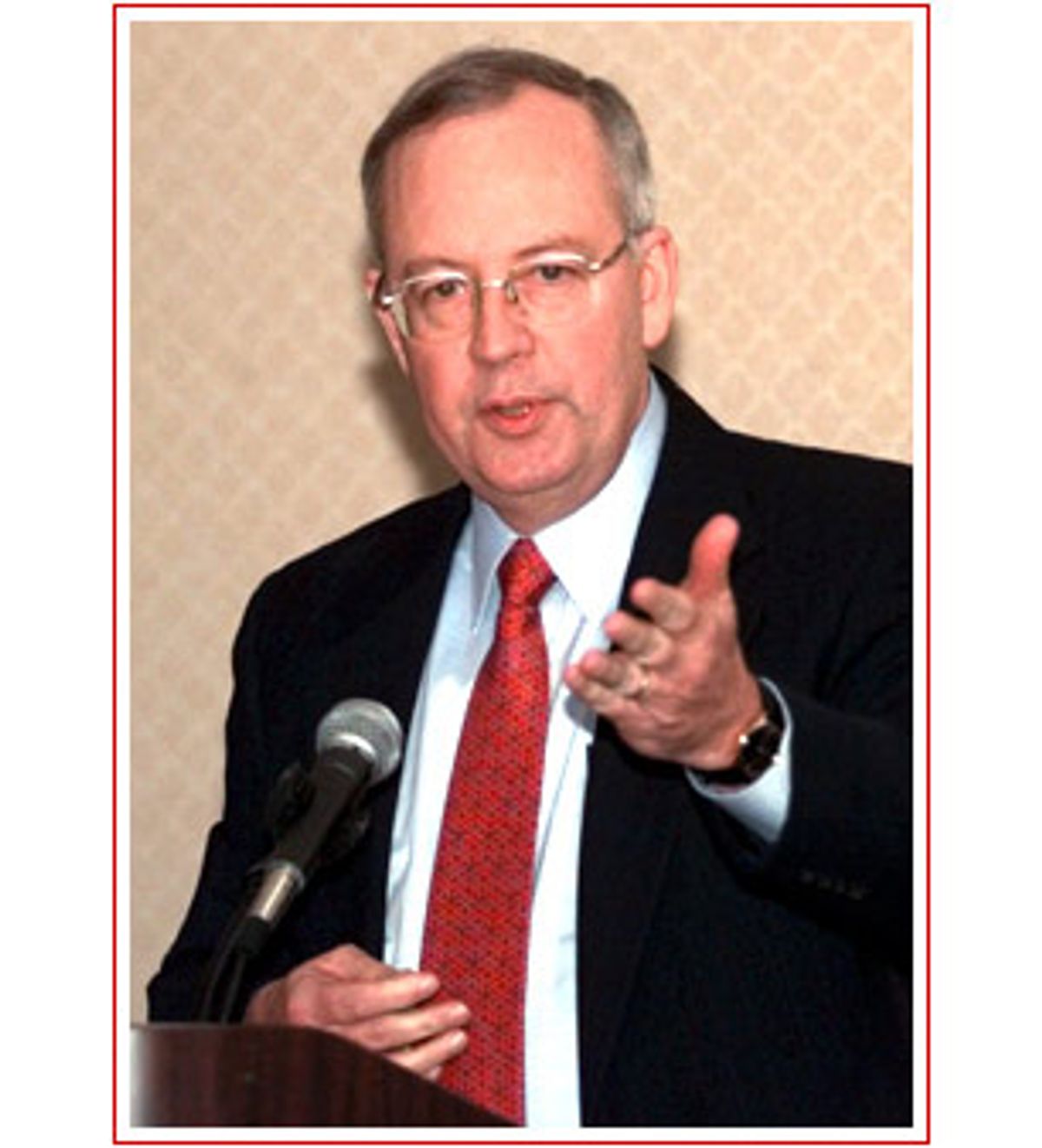

Of his other two main targets, Toobin has a trickier task in characterizing Starr, a shrewd jurist who played his ideological cards very close to his chest. He resolves the issue by making a subtle double claim: Starr, he writes, was at once "a consummate Washington careerist who navigated the capital more by self-interest than ideology" and a "committed conservative" who "came of age at a time when the legal and political systems were merging and one had to take a stand with one side or the other to chart a route for personal advancement." Toobin argues that "politely but unmistakably, Starr had done just that, and by the time he was named independent counsel, he had long ago signed on with many of the people who wanted Bill Clinton destroyed."

More than for ideological zealotry, though, Toobin savages Starr and his team for plain incompetence -- although he also believes that the incompetence was due in large part to the zealotry. In some of the strongest passages in the book, he charges Starr's team with "an obsession with meaningless atmospherics and tendentious 'signs' to their adversaries, an unhealthy interest in using the media to send messages, and a predilection for canine zeal over solid prosecutorial judgment." (In a cackle-inducing aside that may be worthy of Freudian analysis, Toobin asserts that when rumors that Starr was having an affair emerged, what really enraged the independent counsel was that "everyone -- everyone! -- thought the rumor was inconceivable.")

Among many other examples, he scores Starr's competence most harshly in his analysis of how he handled the crucial issue of Monica Lewinsky's immunity. Above all, he argues that Starr's fatal miscalculation was in not granting it early on, in February 1998. "Starr's obsession with toughness and devotion to the Washington conventional wisdom led him to disaster," Toobin says, going on to argue that Starr and his team rejected the Lewinsky deal because they "were convinced she was withholding additional evidence of Clinton's criminality ... The persistence of this myth says more about the fanaticism of those who believed in it than about the evidence against the president." The delay only allowed "the country to come to terms with the fact that the president probably did have an affair with the intern -- but that he had managed to do a pretty good job anyway."

Finally, there is Isikoff, the former Washington Post and current Newsweek reporter to whom Toobin grants the dubious honor of being one of only seven "Key Players" (the Clintons, Paula Jones, Monica Lewinsky, Linda Tripp and Lucianne Goldberg are the others) listed in the front of the book. Toobin accuses Isikoff of being an uncritical water-carrier for the anti-Clinton forces. He reminds us that there were "three important moments in the case when Clinton's enemies used Isikoff to launch attacks about the president's purported sexual behavior: First, Cliff Jackson had given him the exclusive with Jones; second [Jones attorney] Joe Cammarata had set the reporter on the trail of Kathleen Willey; now, finally, Tripp and Goldberg were giving him the biggest story of all [Lewinsky]."

Toobin writes caustically that "Politically savvy journalists might have discounted the allegations, or, more likely, have exposed the motivations of those who had tried for so many years to use sex to bring down this president. But Jackson, Cammarata, Goldberg and Tripp had invested wisely in Michael Isikoff."

So what does it all add up to? Toobin refrains from drawing any large conclusions from his book, but its moral is implicit: We must try to change the cultural, political, ethical and legal realities that helped bring about this disgraceful episode. Politicians should not go on culture-war vendettas; the obsession with "character" is unhealthy and leads inevitably, in a media-frenzied age, to sensationalism and pseudo-scandals; sexual harassment laws should be modified so that they don't lead to endless McCarthyite investigations. (Congress already enacted the single most important change, of course, when it let the independent counsel statute expire.) In the end, though, Toobin mostly finds the whole saga merely repugnant. "No other major political controversy in American history produced as few heroes as this one," he writes. "Instead of nobility, there was selfishness; instead of concern for the long-term good of all, there was the assiduous pursuit of immediate gratification -- political, financial, sexual.

"Chief among the antiheroes," Toobin goes on, "was the president of the United States." Toobin savages Clinton several times in the book -- most harshly for hypocritically siccing his attorney, Bob Bennett, onto Jones' sexual past -- and comments that Clinton reacted to being caught in the Lewinsky affair "not with candor and grace, but rather with the dishonesty and self-pity that are among the touchstones of his character." Nonetheless, Toobin concludes that "the most astonishing fact in this story may be this one: in spite of his consistently reprehensible behavior, Clinton was, by comparison, the good guy in this struggle."

Clinton is the "good guy," Toobin believes, because "the case was never anything more than it appeared to be -- that of a humiliated middle-aged husband who lied when he was caught having an affair with a young woman from the office." He dismisses the other scandals that swirled around Clinton and his administration -- Whitewater, Filegate, campaign finance abuses -- as all smoke, no fire.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

-

This brings us to the heart of the matter, the one issue that remains contentious: Was the case basically about sex, as Toobin argues, or was it about lying? The Washington and New York punditocracy took the latter position from the outset -- and still do. In her negative review of Toobin's book, New York Times book reviewer Michiko Kakutani echoes the sternly moral sentiments consistently expressed by the Newspaper of Record's editors. It's worth examining her review in some detail, because it so closely expresses the mainstream media's view of the crisis.

Chiding Toobin for being "willfully subjective" and having a "tin ear when it comes to the subjects of politics and governance," Kakutani attacks as cynically legalistic his assertion that the Clintons did little or nothing illegal in any of the scandals. "Such arguments suggest that elected officials need not especially worry about ethical conflicts, compromising financial entanglements or reckless behavior as long as they have not committed an actual crime," she writes. She goes on to denounce Clinton for failing in "his constitutional duty to uphold the rule of law."

To take her strong argument first: Kakutani is surely right that Clinton's lying, or legalistic evasions, under oath are far more troubling than the fact that he had an affair. All lies, under oath or not, are disturbing. And even if one were to excuse a private citizen for lying about an affair to protect his family or himself, it could be argued that the president of the United States should never be given a free pass to lie under oath about anything -- not even, for example, to protect the memory of his late mother. As the highest elected official in the land, so this argument goes, his symbolic moral status is such that he must place the sanctity of the rule of law above his own welfare. To do less would be to tarnish his office.

This argument is partially right -- but only partially. The fact that Clinton lied, or told some major stretchers, under oath will be a black mark on his legacy. That is undeniable. Clinton placed himself in a position where, when his evasions had failed, he had to lie -- and history will judge him critically for that. But Kakutani's argument takes too rigid a view of both the law and the presidency. The law is not infinitely malleable, but neither is it a straitjacket. It has a certain amount of common-sense flexibility built into it -- the legacy of the common-law tradition that underlies our legal system. And common sense tells us that not all lies have the same moral gravity. There are such things as extenuating circumstances. It is a one-eyed justice that would judge a man as harshly for lying about an extramarital affair as about stealing a car. And so lofty pronouncements about "the rule of law," while true in the abstract, must be evaluated on a case-by-case basis. This is not cynical debasement of moral principle -- it's the way justice actually works in the real world, and must work.

But shouldn't the president be held to a higher standard? This would seem at first blush to be incontrovertible, but in fact it's problematic. In a democracy, the ideal is that everyone is treated exactly the same -- no one is above the law, but no one is below it, either. To hold the president to a higherlegal or moral standard than everyone else is to violate the spirit of democracy: It is, in effect, to make the president a mini-king. There is a faint whiff of theocracy about it. And it also deprives the president of his rights: It places him below the law. De facto, if not de jure, Clinton was placed below the law during the whole endless investigation of his sex life. To understand this, simply try to imagine a scenario under which an ordinary citizen could be forced through the grotesque sexual wringer Clinton was, with an army of private and public investigators searching for ancient girlfriends, tens of millions of dollars spent, subpoenas and grand jury appearances -- and concluding with an all-powerful prosecutor issuing a report describing for the world how, after a consensual sexual encounter, he masturbated into a sink.

It will be objected that extraordinary means were needed to investigate the most powerful man in the country. But this argument, when set against the actual facts in the Clinton case, is absurd. The Clinton crisis started as a dubious sexual-harassment claim -- an investigation that was instigated and kept alive by the malice, greed and political agenda of its principals, their lawyers and various "elves." It meandered into a fruitless investigation of a failed, two-bit real estate deal -- one that was instigated by a flawed newspaper account, based on the testimony of a con man and a manic-depressive and kept alive by a zealous independent counsel (appointed to replace his more moderate predecessor after two senators who were bitter enemies of Clinton lunched with one of the three judges in charge of appointing independent counsels) and more "elves." And it concluded with the revelation, thanks to the joint efforts of a serviceable journalist, a double-crossing friend, a Clinton-hating literary agent and, of course, more "elves," of an idiotic sexual affair.

That was it. Nothing else was proven. At the end of the day, we know that Clinton is an incorrigible hound dog and that a lot of people hate him. For this, we paid $100 million?

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

-

The pundits at the Times have not found it easy to acknowledge this, but this is exactly the way most of the country saw and still sees the case -- which is why Congress refused, in the end, to remove Clinton from office. Not just Toobin but the American people and their elected representatives, it seems, have a tin ear for politics and governance.

Which brings us to a more slippery argument advanced by Kakutani. She implies that despite the fact that Clinton did not commit an actual crime, he was involved in "ethical conflicts, compromising financial entanglements [and] reckless behavior" -- all of which she thinks Toobin, with his partisan, legalistic approach, seems to condone.

This statement is a classic example of an insidious type of conventional wisdom, in which the belief that "there's so much smoke there must be fire" acquires canonical status. Notice what Kakutani implies that Clinton is guilty of -- "ethical conflicts," "compromising financial entanglements" and "reckless behavior." Leave aside the vague accusation of "ethical conflicts" (this apparently refers to campaign-finance malfeasance -- we're all shocked, shocked to find politicians raising more money than the rules say they should) and the indubitable one of "reckless behavior" (guilty as charged, but many of our presidents, including a lot of the better ones, have been sexually reckless, so Clinton might actually be moving into a higher-class presidential neighborhood than he deserves) and what remains is "compromising financial entanglements." What, exactly, does this mean? What entanglements? The ones that two independent counsels and a Senate committee couldn't find? Apparently, it means that long ago the New York Times pronounced that Clinton was caught in "compromising financial entanglements" -- and once that judgment was rendered, the "legalistic" disposition of the actual case becomes moot. He may have slithered out of this one, but we all know he's guilty of something. Such reasoning does not sit well with paeans to the "rule of law."

Of course, when you hear enough rumors about someone, at a certain point it's natural to start believing them. And certainly Clinton and his administration's habitual evasiveness and, on occasion, outright dishonesty aroused legitimate suspicion -- as did his Mossad-like political response team. (An interesting question posed by the whole affair is to what degree the press and public should assume that super-aggressive spinning is a sign of guilt. At times, it seemed that the Clinton administration's hardball, preemptive-strike approach to dealing with political opposition created more problems than it solved.) Isikoff notes in "Uncovering Clinton" that veteran Washington reporters became wary of Clinton after his less-than-truthful accounts of how he avoided the draft became known -- and such wariness was justified.

But many of the media establishment's suspicions about Clinton were based on nothing more than the fact that suspicions had been raised about Clinton -- a circularity that Toobin doesn't fail to point out. (A much more exhaustive chronicling of the press's numerous sins of omission and commission is found in "The Hunting of the President.") "With an almost comic circularity of reasoning, the very existence of the inquiries about Whitewater were seen as proof that they were justified," Toobin writes. "The New York Times editorial page often spoke this way. 'Much as President Clinton might wish,' the editors wrote in a typical passage, '[Whitewater] ... just won't go away. It keeps popping up in Congressional inquiries and newspaper accounts.'" Toobin cites another, even more Orwellian pronouncement when, on "the eve of one of the many congressional hearings on Whitewater, the paper intoned, 'Mr. Clinton came to Washington promising to end the casual conflicts, favoritism and insider deals of the Reagan-Bush years. The very existence of these hearings attests that he has done little to honor that commitment.'"

It was this sort of assertion, combined with the Times editorial page's consistent and mystifying refusal to see anything problematic about Kenneth Starr and his investigation except for his supposed tin ear for public relations, that caused many loyal Times readers to wonder what was going on with the greatest newspaper in the world. One did not have to be a Clinton supporter to question whether the paper had become too invested in a "scandal" that it helped create (Jeff Gerth's reporting was largely responsible for the Whitewater investigation), was driven by some unknown animus or was simply caught up in an obsessive we-won't-get-beat-on-Watergate-again mind-set.

Of course, the press must be suspicious -- it's a constitutional necessity of the job. Revealing the wrongdoing of the powerful is a noble calling, and it almost requires a mind-set that assumes the worst. But the tough-guy pose can degenerate into a myopic presumption of guilt that ignores nuance and context. And the desire to get a story at all costs can lead journalists into ethically dubious areas.

Which is what Toobin (and Conason, in his review of "Uncovering Clinton" in these pages) argue happened with Isikoff. Isikoff didn't initially reveal to his readers the ulterior motives of those feeding him information because he didn't want to blow his sources. But at what point does the legitimate desire to protect a developing story justify the withholding of important contextual information about that story? To be fair to Isikoff, he found himself in an almost unprecedented situation -- and he acknowledges in his book that he was disturbed by it. Still, it's hard to escape the conclusion that he should have looked harder into the motivations and connections between his sources -- and revealed them earlier to his readers.

In his book, Isikoff also reveals crossing a Rubicon in his attitude toward Clinton: In August 1997, he writes, he overcame his earlier doubts and decided that "Clinton's serial indiscretions" -- including the affair with Lewinsky, whom Linda Tripp had told him about in April -- were worth covering because "Clinton was far more psychologically disturbed than the public ever imagined ... A culture of concealment had sprung up around Bill Clinton and, I came to believe that summer, it had infected his entire presidency." Considering the hard-working-Joe, just-the-facts-ma'am pose Isikoff has hitherto taken, this lofty moral rhetoric strikes a somewhat jarring note -- one not made more harmonious by the murky nature of the allegations against Clinton and the fact that by this time Isikoff knew he was in possession of an explosive story that could become a bestselling book.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

-

Did any winners emerge from the Clinton crisis? Certainly not Clinton, whose most unattractive personality traits were revealed for all to see. Nor did the players in the "vast right-wing conspiracy" fare better. The higher-minded of the "elves" no doubt liked to imagine themselves as fearless fighters for justice, but they were exposed as tawdry dirty tricksters, Machiavellians out to destroy their enemies by any possible means. In the age of Gingrich, Limbaugh and the Christian right, this version of "conservatism" has attempted to swagger its way into acceptance as a legitimate right-wing stance -- but it is a cold-blooded, absolutist, instrumental morality that has much more in common with the ends-justify-the-means approach of the Stalinist left than with true conservatism, which is based on measure, decency and other intangible virtues.

Indeed, one of the most depressing things about the Clinton crisis is that it legitimized a raw and ugly strain in American life, the worship of sheer power. If we can just destroy this guy, the Clinton-haters believed, no one will care later how we did it: The facts on the ground will become the new reality. For his part, Clinton let a lie fester for eight months, calculating whether he should tell the truth by watching the polls. The scary thing is that in an age of hate-spewing talk radio, buccaneer capitalism and I've-got-mine-Jack online libertarianism, they both had it right.

But there was one winner. In an age when political bile and the need to be constantly entertained vie for cultural supremacy, it is probably fitting that the story of the last presidency of the 20th century was written, right up until its ending, by a brazen hack. More than anything, the whole episode represents the triumph of Lucianne Goldberg: She may not have destroyed Clinton, but she succeeded in turning the entire country, at least for a time, into a gigantic pulp novel.

Shares