My husband, a writer, won a nice award last year. He stood at the lectern, accepting his very due reward with a lovely mixture of humility and giraffe-like awkwardness. I sat on a folding chair in the middle of the audience, pregnant, wanting to kiss him. And also wanting to rush the stage, push him off and accept the award myself. I would be twice as humble! Yet I would be erudite! I would remember to thank my mother! The problem was, I hadn't (and haven't) written a book.

I read my husband before I met him. I read him in the local alternative weekly, where he wrote with the vocabulary and grace of an old man. I followed his career, in a vague way. When he edited an anthology of Northwest writing, I was irrationally enraged. It was the book I was born to edit, if people can be born to edit things. Never mind that I was, at the time, neither a writer nor an editor. (I was a student who spent most of her time going to rock shows.)

Eventually, I became a staff writer for the same weekly. As the courtly publisher led me through the newsroom on my first day, he paused at the paste-up table and, with a flourish of paternal pride, presented Bruce. I found myself staring into the face of ... a boy. This person whose career I cursed and envied was the exact same age as I. There was only one thing for it: Reader, I married him.

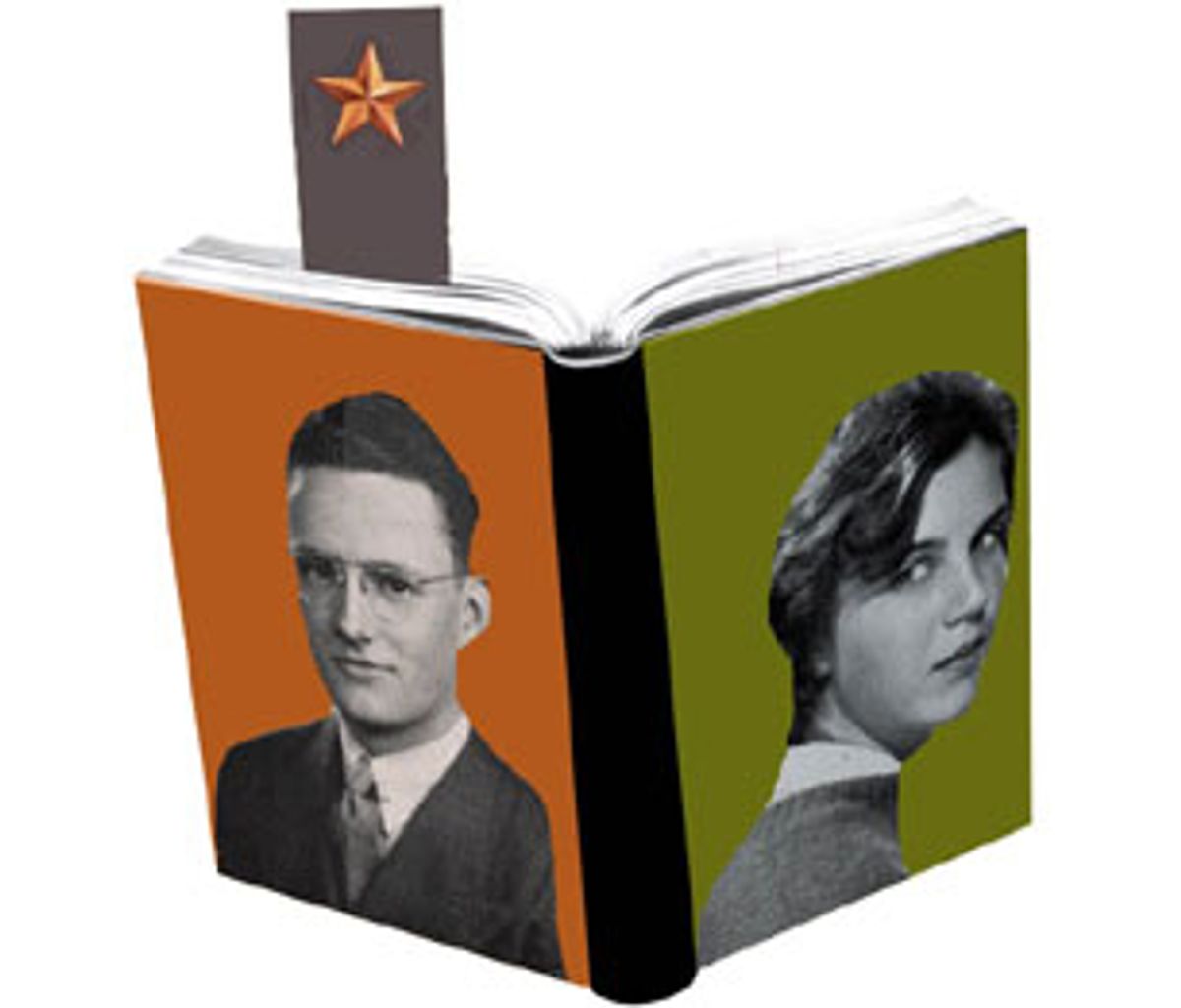

We now both make nice livings as writers. Bruce's is nicer, in size and in provenance. He has written a well-published and well-received book. I have not. He is a contributing editor at a prestigious national magazine. I am not.

The explanation seems simple: My husband is by nature a tortoise and I am a ... well, hare isn't really it. Maybe a sloth. He spent his 20s accruing experience; I spent mine accruing experiences, most of which occurred late at night in stinky bars. I dwelt in the green, oxygen-filled glade of my promise, my talent, my potential; Bruce walked the narrow streets of realized potential. He went to New York and met the right people. He mastered reporting, criticism, editing. He learned to type really, really fast. In short, he worked.

That is the reason I give for his success, when one half of my brain starts to nag at the other. But the problem with comparisons is that, taken to their logical conclusion (a bad habit of mine), they demand one entity to be, simply, better than the other. Bruce, it seems to me late at night, is more successful than I because his work is better. And -- since writing always seems to me so close to one's truest self, it would follow that his work is better because he himself is better. Nights can be hell.

I wonder how this tension works itself out in the higher echelons of dual-writer households. Does John Gregory Dunne flop about on his pima cotton sheets, tormented by Joan Didion's secure place in American letters? Does the wildly talented Siri Hustvedt secretly wonder whether she'd be more famous than her husband, Paul Auster, if only she didn't have such a weird name? When two people do the same kind of work, an eclipse is bound to occur.

My husband, with his glowing corona of success, is the sun (this despite the fact that he is a dark, surly, beetle-browed Norwegian). I'm sunnier in temperament, and I'm not without my uses and successes: I take care of the baby, get good freelance work and generally try to make the world pleasant. But my husband's star is rising. It's only a teensy nova in the greater literary universe, but in our house, it shines damn brightly.

I'm comfortable with that bright light; I've basked in it all my life. I am the worshipful little sister of a Sun King older brother, who was good at every last thing he tried and, absurdly, grew up to be a rock star. Not a metaphorical rock star, but an actual one. The kind with groupies and platinum records and paranoia. I grew up thinking this: Boys are for shining.

Among the various, uh, eclectic boyfriends of my adulthood there has been one constant: They all excelled at what they did. The singer got good radio play; the illustrator drew pictures for all the right magazines. Even the creepy physicist was a tenured professor. I seem to have a success fetish.

It's a well-documented phenomenon: the woman who can't be it, so she marries it. This is a retro, mid-century kind of neurosis, one that goes well with 1940s red lipstick and vintage swing-dancing dresses. In fact, our mothers' mothers would not have thought it neurotic at all. My grandmother told me quite frankly that she married my grandpa because his line of business -- the fur trade -- fascinated her. It never occurred to her to go and get a job where he worked. My grandmother's suppressed ambition, if you think about it, yielded the same joyless crop as my own unrealized potential: a sneaking sense of what might have been. Only in my case, it was voluntary. My attraction to successful men was a roundabout gambit of avoiding my own ambition.

Until I became a writer, that is. I instantly and joyously abandoned my love of leisure once I discovered the great laugh of my adult life: People will pay me to write. I have since been fueled by a colossal ambition unsuspected in those indolent, smoky, rock 'n' roll-filled days of yore. And funnily enough, my ambition and my writing thrive in the bright sunlight of Bruce's success. Sure, I want to kill him when he turns down work for the New York Times. Sure, I resent playing the little woman when we go out to dinner with his editor. But, then, there is his shining example of hard work that paid off.

And there is, too, something else, something deeper: a kind of distracter effect, as when you point out the window to divert your friend's attention and then grab the food off of his plate. While everyone is looking over there, blinded by Bruce's shiny ascent, I'm toiling away. The pressure is off. Go, you all, and gaze at his nimbus. I could use a few minutes of quiet time.

Shares