"Alaska Airlines is a sharp, well-run company. A good bunch of guys," the airline pilot says, shaking his head. A first officer with a major airline, he knows how it feels to have a crash in the company.

"Someone trusted you with their lives, and you let them down," he says. "You just hope that they find it was something that couldn't be helped, something beyond anyone's control." Statistics don't bear out that hope. Most often, it's the pilot's fault. Less often, a mechanical failure.

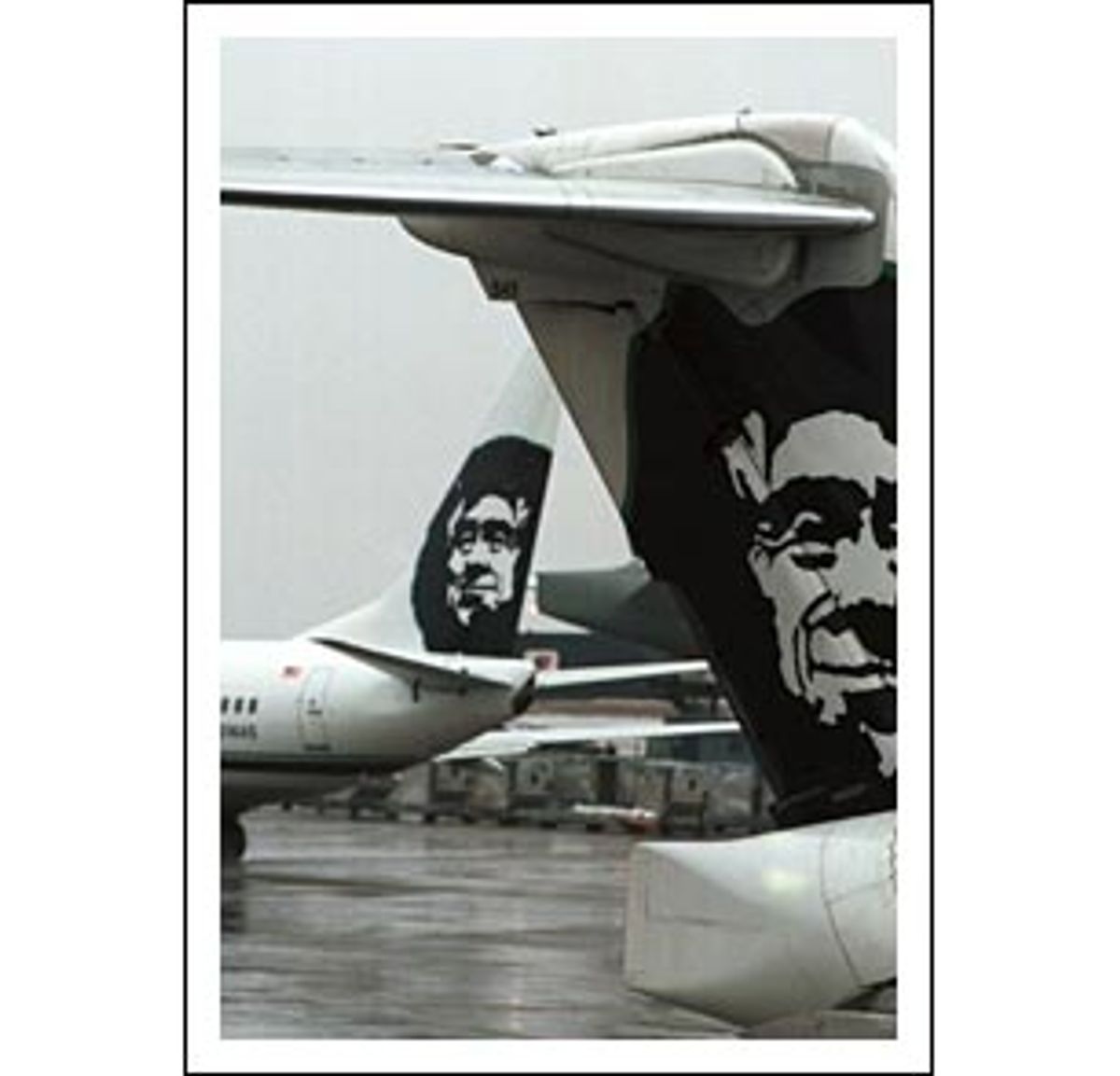

At this early stage, it appears that mechanical trouble reported by the pilots contributed to the crash of Alaska Airlines flight 261. Industry insiders agree that the airline has always run a responsible company, not some sleazy little cut-rate upstart.

But even the top-flight airlines, the "majors," as they're called in the trade, don't have perfect maintenance records. Keeping aging jets airworthy is an expensive and time-consuming job, one that glides in and out of gray areas. And given that the airlines are motivated mostly by profits, it's always been surprising to me how much leeway they get from the Federal Aviation Administration on maintenance issues.

Commercial jets are complex machines with up to 100 different systems. Each system (fuel, controls, engine, pressurization) can have hundreds of parts. Mechanics, hired and trained by the airlines, tend to specialize in a particular system or set of systems.

A small airplane's engine is rebuilt and replaced after a certain number of flight hours. But the airlines gave that up long ago. Now they track the health of their machines using "condition monitoring." The engines are stuck full of probes, feeding data to other systems and the black box. That information on engine performance gets regularly uploaded into a huge database of other engines. If the engine in question still looks strong by comparison, the FAA allows the airline to let it ride. Some engines fly with only minor repairs for thousands of hours past the original recommended rebuild time.

It sounds like an efficient program -- why rebuild an engine that isn't going to fail? The engines are constantly tuned and upgraded with new parts as they need them. Airlines schedule regular "A, B, C and D" checks. The frequent "A" check is basically a one-day walk-around. The "D" (done every five or six years) is a complete tear-down and detailed inspection of all systems. The Alaska Airlines jet had a recent "C" check, one step below the in-depth "D."

But even with such obsessive and almost-constant scheduled maintenance, there's a problem: Cutting costs is the key to survival for struggling airlines. Half or more of an airline's expenses are fuel and labor costs. Fuel costs are fixed, which leaves labor to cut if profits are hurting. That means hiring lower-paid staff and streamlining procedures that take valuable time. If maintenance can be put off and engine life extended, that's a direct bottom-line boost.

"Negotiating on maintenance issues, sure," says one mechanic who has worked with a major airline. "Airlines are always writing a letter to show some data to some FAA guy to say that some engine doesn't need to be tested so often. Every [limit] gets changed."

Can in-house mechanics be pressured by a penny-pinching boss? Certainly, most work hard and take pride in their jobs. But one technician, who worked for 15 years in the engine-overhaul business, says they can't help but make judgment calls. "Not every technician will have the same opinion," he says.

When parts come up for inspection, mechanics have to make some decisions -- take them apart for a closer look? Pass them? Fail them? "One guy will pass it, another won't. We would scrap something, the customer would ask to send it to [the engine manufacturer] and their technicians wouldn't scrap it. These are gray areas, obviously."

Here's an example of where their employers' loyalties lie. The downed Alaska Airlines MD-83 was due for an inspection of its horizontal stabilizer hinges -- the stabilizer the pilots reported having trouble with just before the crash. The FAA "airworthiness directive" (AD) mandating the hinge inspection for all MD-83s included comments from airplane operators. One was a plea to perform less stringent inspections, and another asked the FAA to allow previous, less stringent inspections to count toward the AD compliance.

Fortunately, the FAA didn't listen and issued the hinge-inspection AD anyway, at an estimated cost of over $7,000 in labor per airplane. It offered an 18-month window to comply, so that the cost wouldn't put undue hardship on MD-83 operators. Alaska Airlines' jet was within that 18-month time frame when it plunged into the ocean, so even if a hinge failure did contribute to the crash, the airline was operating well within the FAA's legal guidelines.

The stabilizer-hinge inspection was ordered because rust was found on older planes. Some mechanics doubt that Alaska Airlines' newer MD-83, built in 1992, could have developed enough corrosion to cause a catastrophic failure.

But many pilots and mechanics have stories of petitioning the FAA to change a certain maintenance procedure only to be ignored until a crash calls attention to the issue. Likewise, the FAA tends to check up on airlines only when something forces them to. A disgruntled employee reports a record-keeping discrepancy. A crash investigation reveals an improper repair procedure.

That tricky relationship between the airlines and the FAA, plus the agency's low staffing, means that airlines are often left to their own devices when it comes to abiding by maintenance regulations. "The risk to letting agencies self-police is that there's no real threat from FAA," says an airline pilot who spent his early career in Alaska (not at Alaska Airlines). There, he says, he flew for "nasty little operators that cut every corner there was," and never once saw the FAA drop in.

Clearly, the FAA is more reactive than proactive. Airlines are desperate to cut costs. Who has the incentive and the power to change the system?

You do. I do. Everyone who buys a plane ticket does. The only way to force airlines to spend money on maintenance is to pay for your trip. Pay for the pilot who spent 10 years flying in Alaska and knows how to land in a snowstorm. Pay for the flight attendant with a few evacuations under his or her belt. And pay for the mechanic who's seen turbine blades fail and insists on searching for the nearly invisible cracks. After all, the people on the plane are those with the biggest incentive to make sure it doesn't crash.

Shares