Today I watched a woman give up her child.

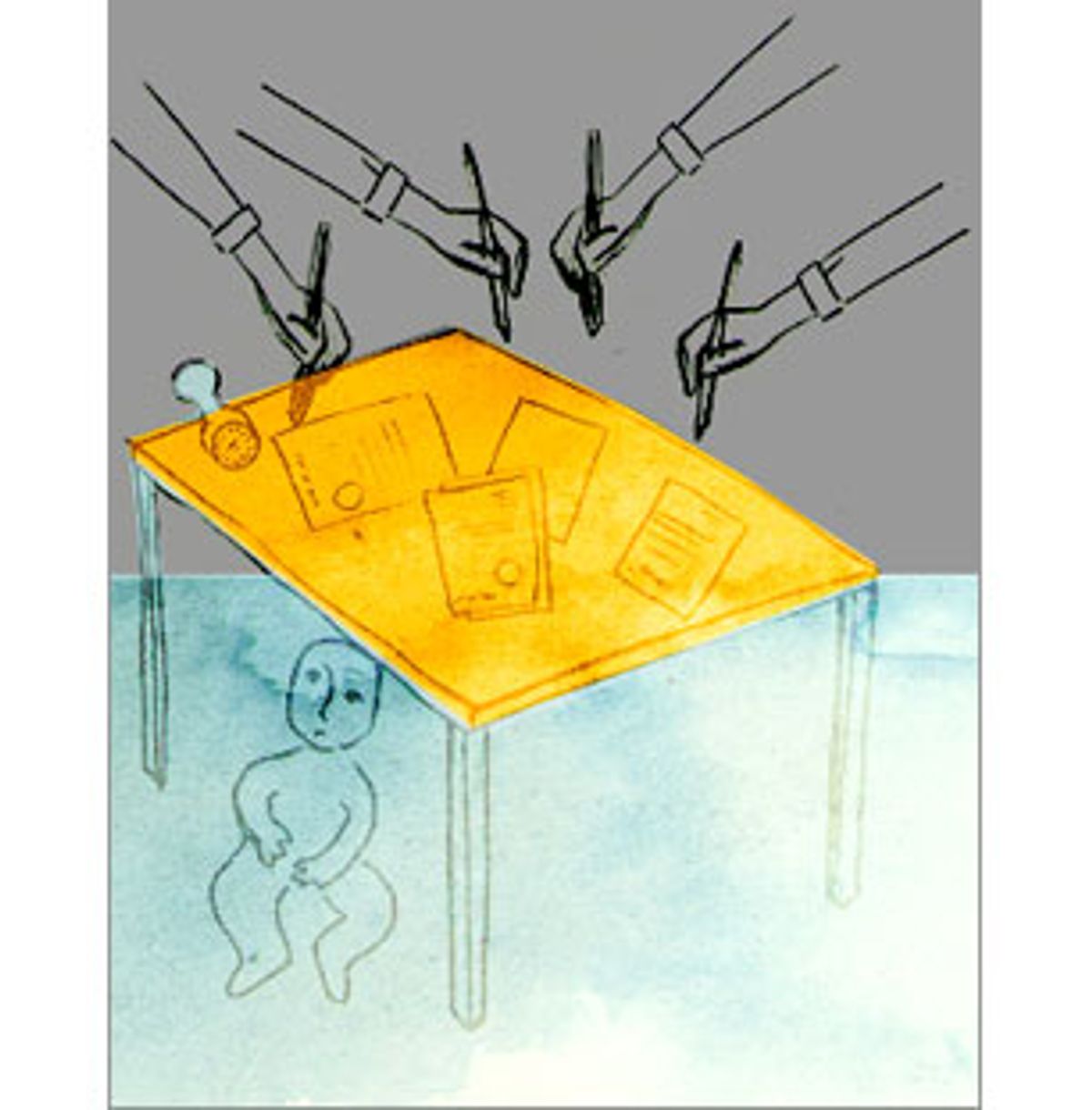

By "watched," I mean that I sat in an agency

conference room at a table with the mother and her family as she signed the papers to

relinquish her child to the state. There was no scene like you might expect -- the caseworker

tearing the child from the mother's arms, the mother collapsing to the floor in hysterics as her

child was carried away. No, the mother sobbed silently as she signed four copies of a series of

papers that said that she would no longer have any rights whatsoever to her child.

As much as

I've wanted this for the child, it was distressing to witness -- an event so packed with meaning,

yet plagued with the familiar trivialities of buying a car or a house. The caseworker read each

page out loud before allowing the mother to sign. After she signed, the mother slid the paper

down the table for me and an agency employee to sign as witnesses. The notary sitting next to

me then stamped and dated each page.

One of the pages had a place where the mother could

write down any thoughts or sentiments for her child. She breathed deeply and then started to

write. As her pen scratched across the page, she started to shudder and tears streamed down

her face. Her mother, sitting next to her, put her arms around her and pressed her head into her

daughter's hair as she wrote: "I love you very much and I never wanted to stop fighting for you."

Two signatures and a notary stamp

later, it was done.

As the child's Court Appointed Special Advocate (CASA), I've been very

involved with this family for the past year. Still, I felt like I was

witnessing something intensely private, and as I signed and dated each page,

I felt like my presence was a violent intrusion into one of the most sacred

areas of family life.

The child, now 17 months old, was placed in foster care when he was 3 months

old as the victim of violent abuse. While the mother was not accused of

inflicting any injuries on the baby, she had failed to protect him. She didn't

take him to the hospital when he was injured, and when Child Protective

Services finally got involved, the baby had complete or partially healed

bone fractures throughout his body. He also had a scar on his leg from a

cigarette burn. His injuries were so severe that, for his first three weeks in

foster care, he was carried horizontally on a pillow.

Last summer, after spending some time in jail awaiting trial, the mother had

pleaded guilty to failing to protect her child, and received lifetime probation

and a no contact order. After months of struggle in juvenile court, she finally decided that it would be best for the baby, whom she

hadn't seen in over a year, to relinquish her rights. Her own mother, the

baby's maternal grandmother, had been refused by the state for placement of

the child, due to a long history of failing to protect her own kids from

abuse and neglect.

At some point, it must have become clear to the mother

that to fight any longer would only keep the child in foster care so long

that he might never be adopted.

After the mother signed the consent papers, she had a final visit with the

baby. The state requested special permission from the mother's probation

officer to allow the visit, since the no-contact order was still in place.

I carried the baby into the conference room and put him on the floor. He

was clutching a sippy cup full of milk and looked around at all the people,

eyes wide. In addition to her own mother, the mother had brought her new

husband and her teenage brother and sister. The baby looked from face to

face and then shuffled back to me. I gave his mother a bag of Cheez-Its,

and she tore it open. The baby hesitantly walked over to her, got a

Cheez-It and returned to me. The grandmother reached for a large

Toys "R" Us bag behind her. "Look here! See what I have?" She pulled out a

Fisher-Price tricycle. Tempted, the baby toddled over to her.

His mother observed him cautiously at first, reaching out to stroke his hair

as he toddled by, straightening his sweatshirt when it rode up on his

stomach. She asked questions about his health, and his grandmother asked

whether he was talking yet. The next hour was filled with more gifts,

occasional shyness, laughter and baby babble. At one point, the baby fed

each of us a Cheez-It.

He seemed to put us in order by how often he'd seen

us in the past year. First me, then his grandmother, who had received regular

visits, then his aunt and uncle, who he'd seen twice in the past year, and

finally, his mother. "Oh look! He gave YOU a cracker!" the aunt said

enthusiastically when he gave one to his mother. Eventually, the baby was

tearing around the room, playing with each of his new toys, laughing and

interacting with everyone, occasionally looking at me as if to say, "This is

OK, right?"

After an hour, the caseworker said it was time to say goodbye. The

husband, aunt and uncle left the room, leaving only the mother, the

grandmother, the caseworker and me. The grandmother picked up the baby,

hugged him tight and kissed his face vigorously several times. He giggled

and pushed away, wanting to be put on the floor.

She passed him to his

mother, who held him over her newly pregnant belly, and tried to hug him.

He looked to me, giggling. She turned him to face her, tears again

streaming down her face, and said, "You be good. I love you. I love you."

She hugged him tight, and he giggled and looked away. She pressed her head

against his and hugged him again, and then returned him to her mother and

said, "OK." Her mother put him on the floor, and he toddled to the door.

The mother and the grandmother called after him, "Bye-bye." The caseworker

opened the door and he raced out.

The caseworker had told the mother that if the visit became too emotional,

she would have to cut it short to prevent the baby from becoming upset or

afraid. So although the mother cried openly while signing the consent

papers, she stifled her tears during the visit until she said goodbye.

I don't know what was going through her mind during all of this. She must

have prepared herself for the fact that he was unlikely to recognize her,

and that he might not even want her to hold him. She might have been

thinking about what could have been -- her new baby, her new husband and

this baby, a happy family. She might have remembered when her own mother

relinquished custody of her so that she could live with a relative in a

different state. She might have worried about whether the state would take

her new baby.

As we have gradually come to learn, the meaning of the word "family" is

fluid. When this mother signed all those papers, she made sure to check

every box that would enable her child to find her, to contact her, to know

everything about her. She enabled his future adoptive family to contact

her, to send pictures and to coordinate visits if they desire.

At the same

time, she understood that she might never see this child again. His new

family could change his name, keep their own identity a secret, and he might

never try to find her. But she brought presents, held her tears, held him

tight and told him she loved him anyway, even if the goodbye was forever.

The way she cared for her baby, or failed to, resulted in her losing him. I

expect she will live with that loss for the rest of her life. She will

probably see flickers of the son she gave up in her new baby, in children on

the street and in the mirror. Throughout the year, I have doubted whether

she was or would ever become capable of being a mother, with all that that

word entails.

But today, in one of the worst situations a

mother could be expected to endure, she did the right thing. She gave her son a chance to

have a permanent family, and she loved her son all the way through saying

goodbye. And in those moments, I saw the mother she is capable of

becoming.

Shares