"Rule No. 1: Don't screw the students," he said, sitting back down from shutting the door. I coughed tea all over my sleeve, swallowed and continued staring at him, nervous, befuddled. He puffed his cheeks, sighed and gazed with half-open eyes toward the ceiling, exhaling:

"Well, I don't give a damn what you do in your personal life, anyway. Just don't screw anyone in this office, OK?"

He stared at me a moment longer and turned toward his desk, both hands feeling his pockets for a pen. "That's all. See you Tuesday." I grabbed my bag and said meekly, "See you later," closing his office door behind me. So this was teaching. This was tenure. This was what I've spent the vast majority of my life striving for. Dear God.

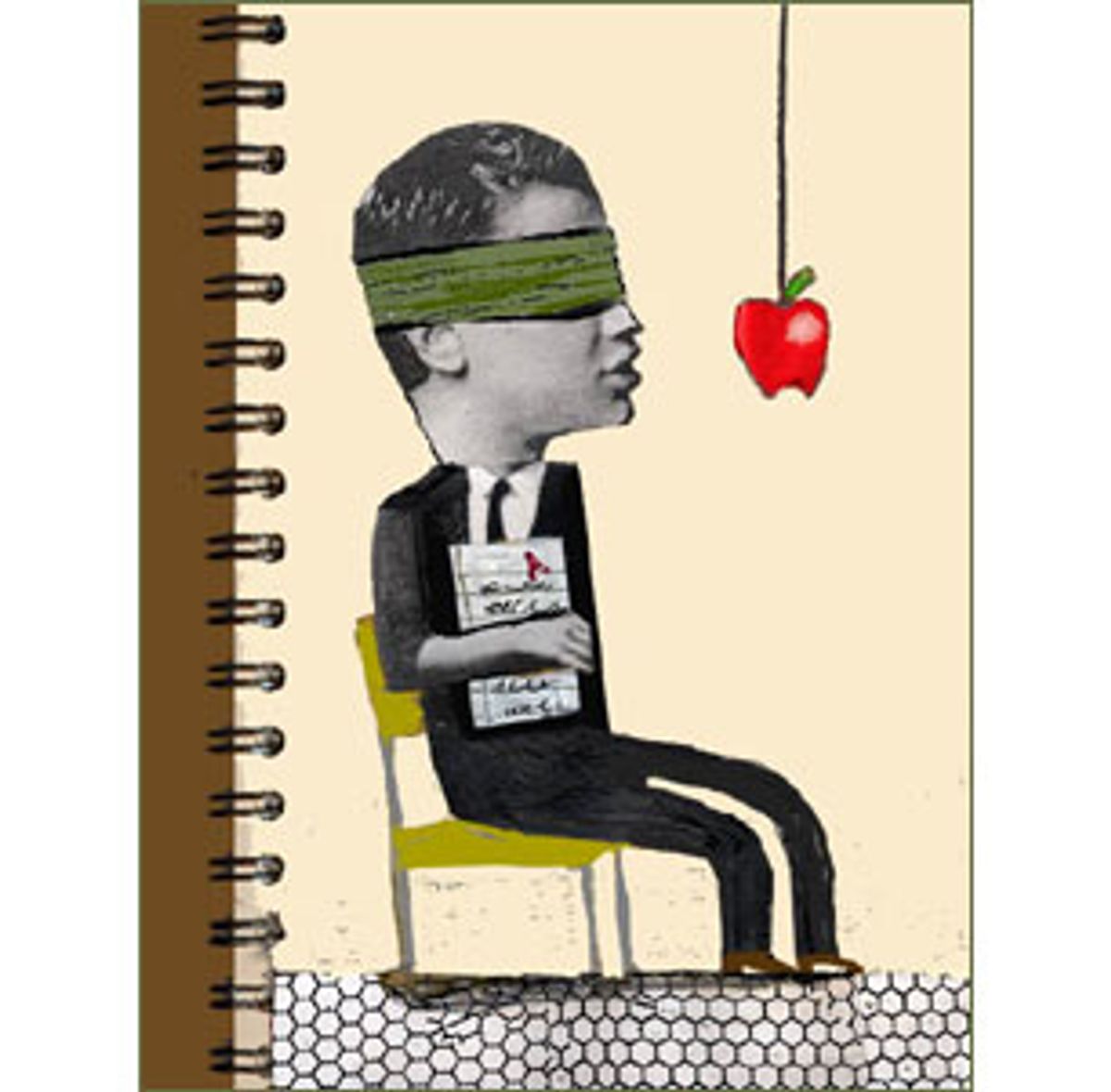

I offered to be a teacher's assistant for a class in American literature to brighten up my doctoral applications, but what began as an obligatory extracurricular exercise soon took over my entire life. Within three months I somehow went from grading papers and taking roll to delivering hot meals and shopping for his niece's Chanukah presents -- and all for a good letter of recommendation. By the end, I did not learn how to teach a class or properly grade a paper, but acquired a far more important skill: how to manipulate the system -- and students -- to gain financial and personal rewards. I saw how to work it; the dirty tricks that can earn you more nap time, more sick days, an all-expenses-paid trip to Italy, a handicapped parking spot, a free personal shopper and more time to do anything and everything except teach.

I first heard of him my second semester in the M.A. program, his name always accompanied with a roll of the eyes, a dour look or a pejorative comment: "He's a fascist." "He's a misogynist." "He's a pervert." "He's insane." "He tries to touch you." "He reeks of apricots." It all piqued my interest enormously. I'd spied him across campus hobbling along like a hobo in a Depression-era cartoon, a "Little Rascal" all grown up, then half deflated. What was this guy about? Why was he teaching? I was hooked and had to know more.

I quickly enrolled in his Mark Twain seminar and was wholly disappointed -- not because he didn't live up to his notorious reputation, but because people hadn't talked enough about him. He was mesmerizing: The mauve, threadbare oxfords hanging out the back of the clownish red polyester sport jackets, tapering down just past the baggy butt of thick olive Farrah trousers; his office, like some bad '70s modern art installation, with its explosion of manila envelopes on the floor, on the desk, covering the computer, sticking out of drawers, cluttering-up chairs; his penchant for reading his entire dissertation over the course of three classes, stopping only to quietly burp in his hand; his effortlessly changing a B to an A on an exam if you simply asked -- all these things made him more fantastic, a living, breathing Falstaff, only more Wilde in nature.

So when I saw him the next semester and he asked me to T.A. his class, squeezing my hand with his clammy palm -- his salt-and-pepper monobrow curving like the forehead of a shar-pei -- how could I say no? I needed something to fill up the "Please List Any Teaching Experience" box for my applications, and could surely pull a good letter of recommendation out of him.

"Yes, I'd love to," I said.

"Thank you, handsome young man" he said, winking, before turning around and hitting his head on the library door.

We met the next Tuesday. He welcomed me in, shut his office door and in a cracked, faux-authoritative voice, tried to muster up the professorial decorum to deliver words of wisdom to the eager-eared, budding new scholar: "Rule No. 2: As long as you don't fuck the students, you will never get fired. They can't do anything." With tea still all over my sleeve from Rule No. 1, I responded shakily, "Really? Um, that's great."

I was to pick up papers once a week, provide a short list of comments for improvement and write the grade in light pencil on the upper right hand corner. As I turned to leave, he said, "Oh, and by the way, on Tuesday, could you please pick my mail up from 212? My back is troubling me. Thank you." "Ahh, sure," I said, just getting a hint of the mess I had gotten myself into.

In the following weeks, tasks piled up like so many used handkerchiefs in his perpetually full backpack: "By the way, could you please keep track of the roll? They don't pay me to be a goddamned secretary." "Listen, could you bring my mail back down to 212? My arm is killing me." "Would you mind terribly putting the grades in a grade book? You will have to buy one. Oh, I trust your judgment, don't be foolish."

It was amazing what he got away with, and how he managed to squeak through the machinery so unscathed. He no longer prepared for classes, graded papers, wrote anything, answered his phone, held office hours or demonstrated any interest whatsoever in students or teaching. And the school couldn't fire him. Apparently, for about five years his teaching evaluations were so bad that the English department went so far as to warn students against taking his classes.

This sloth, this callousness: Were these the fruits of tenure? Sure, I had seen other tenured professors slack off, check out busty freshmen in scandalous fashion while the T.A. ran the show, but at least they seemed interested, at least they published books and tried to appear active in the field. He, on the other hand, did nothing. The university just pickled him, put him in a jar and let him rot in his own juices. Tenure: the last saving grace of the crumbling ivory tower? What the hell was I thinking wanting to be part of this?

"Why don't you retire?" I asked him after a particularly exhaustive rant about the evils of teaching. He was over 60, had been a professor for more than 30 years and should have a good pension coming. His only response was "I need the money," winking, contorting his face like a shrunken witchy-poo apple-head you see at Halloween.

By late November, I was running the entire class, keeping track of roll, correcting every paper, every test, every assignment, taking all the grades. I began to feel guiltily responsible for the class; I knew what those sophomores -- those taking out loans, working through school, trying to better themselves by being the first in the family to graduate from college -- were going through. I was going to be a teacher, after all, and had to get used to such adverse situations -- plus, I needed that letter of recommendation.

"I also need to talk to you about my letter. I am putting together my applications and was hoping ..."

"Listen, I told you I would do it. I can't even think of it now. Ask me in a month."

"But the end of the semester is too late. I need the letters now. I tried to tell you about this."

He spoke very softly: "I can't do them now." He was obviously getting great sadistic joy out of manipulating me. What a sexy new game: to torture a person he actually liked, one who had taken care of him for the past three months. The whole thing was so tragic, so dark and Freudian.

He called the next week and left a message that he had the finals for the entire class, blue books for a two-day, six-hour final exam. "Ahh, is this working? Pick up. James, you need to pick up these books by Sunday. Saturday night is good. Meet me at my apartment. We can talk about the letter of recommendation." Beep.

He was waiting in the lobby when I showed up, standing in a tired terry cloth bathrobe with stains all over it -- earth tones, browns, tans, light greens, bodily hues that bled together in a calico pattern. He handed over the final exams in gigantic folders: "When these are done we can work on the letter of recommendation." I turned around, went down the elevator and corrected papers until 4 that morning.

He called six days before my applications were due and mentioned, again, that he didn't have time to write the letter, but suggested that I write it instead, and he would correct it as he saw fit.

We met in a small cafe a few blocks from his house, a well-lit hole where old Chinese men played checkers and speed freaks sipped well-sugared iced teas while picking their cuticles with ballpoint pens. I had everything: All 54 final exams for his two classes, a meticulously kept roll sheet, all grades, all late papers -- everything -- and, most importantly, my unsigned letters of recommendation.

He made room to the right and asked me to sit, his right knee touching mine. He took the grade sheet and read each student's name aloud: "Maria, you have that she earned a B-plus. She's a sweet girl, let's give her an A-minus. Brandon, B, he gets a C-plus. Marisa, A-minus, she doesn't deserve it: B." And it went on. Everything that any student had done in the class -- the countless revisions, the tutoring sessions, the study groups, the months of sitting through his lectures -- every one of these efforts were erased in a second by the whim of his pen.

"Here is the roll sheet for the entire semester. Do you want this?" I said.

He folded the grade sheet up into his shirt pocket, took a sip of coffee and said: "There are some things you do not understand. Some things are more important than just turning your papers in on time, showing up for class. The grades are done." He grabbed his coat to leave.

"You, you need to sign these recommendations. Here, you said you would sign these, and the back of each envelope. I have them all printed up."

"Ahhmm, quickly, I don't feel good. Where."

I shoved letter after letter in front of him; he signed each without looking. After the 10th, while I was busily licking and sealing each envelope, he sighed, slid down the bench, put on his jacket, again, and prepared to leave.

"I, you have to sign the back of each envelope. They won't accept them if you don't."

He stood up, and with a vicious eye, snorted: "Listen, I am not a fucking secretary. You sign the backs, goddamn it. I am sick. I have to go now. Bye bye."

"I can't; you have to sign the backs or the schools will not accept them. I need these. I am already late. Please."

He stepped closer, now yelling: "Listen, your management skills don't work on me, man. I went to Harvard Law School. I graduated from Columbia. I graduated with honors. You don't tell me what to do! That fucking school can't tell me what to do -- that bitch the dean can't tell me what to do. I went to Harvard. Do you understand that? Hhaarrvvaard. You are an idiot. I won't take orders from you. Fuck you." His voice broke. The entire restaurant was silent, staring. I was sweating. Nobody moved. He walked out.

So this was it -- I finally got it. Another tragic tale of an Ivy League-educated professor teaching at a state university, never meeting his rosy expectation of an active life in the academy, never up for a Pulitzer, never published in the New Yorker, never a chair for the Modern Language Association, never content expounding high art to the lower class, never a scandalous affair with a fawning, impressionable grad student -- left behind with only the memory of the genteel Harvard men, the ascots, the nights reading Gide, lusting after Marais, speaking Latin and exploring Hellenism -- it all ended 30 years ago when he got hired 2,000 miles from home.

We haven't spoken since. I recently saw him from afar, walking across campus, now with a cane, more hunched over, carrying his own backpack, beaten -- his trousers lower, the cuffs hanging over the back of his Wallabies, creating new holes with each weary step forward.

Shares