At the end of a narrow road, deep inside one of the few

remaining forests in New Delhi, I asked my taxi driver to honk

the horn. "Let's see what happens," I said.

But the driver was reluctant. He stepped cautiously from his car

and scowled at the dense stands of sissoo and teak. He appeared

to be as intimidated by this obscure patch of Indian forest as I

had been by the crush of cars that converged recklessly at the

traffic circle where we had met an hour earlier.

"Go on," I coaxed.

The horn blast that followed smashed through the woodland

tranquillity like squealing tires on suburban asphalt. But no

sooner had the sound begun to fade over the forest canopy than it

was overrun by a chorus of barking hounds. "It's the Doberman

pinschers," I whispered, as if their ruckus was a sign foretold

to me by an Indian mystic and not, as it had been, by a

middle-aged porter at New Delhi Railway Station. "Find the dogs

and she will be close," I said, repeating his cryptic

instructions aloud.

Wary of who "she" might be, or perhaps girding himself against an

onslaught of salivating hounds, the driver stepped back inside

his taxi and closed the door. "When your business with the lady

is complete, you will find me waiting," he said. "Please don't be

hurried. Price is same."

Among the taxi drivers who swarmed around me that morning trying

to hustle guide services, this one seemed to appreciate my sense

of off-the-beaten-path adventure. I'd already seen the Red Fort,

the presidential palace and Parliament buildings; been thrust

unwillingly into gem emporiums and carpet shops; and even toured

the Birla Temple twice (the second time because my driver didn't

seem to understand my use of the word "no"). This time, I chose a

guide carefully and explained my expectations clearly. "I want a

unique travel experience," I told the driver. "I want to meet an

Indian queen." Now, here we were at the first difficult juncture

and he appeared to be abandoning me.

"If you hear me shouting for help, you will come running ...

won't you?" I asked.

But the driver would have none of it. "I drive the taxi," he

said. "For heroics you must call Mr. Rambo."

I suppressed an urge to update him on American action hero

archetypes and instead smiled anxiously, wondering who then would

come to my rescue if I should run into difficulties. As I

traversed a narrow trail leading deeper into the forest, my

thoughts of rescue escalated as the sound of the dogs grew

louder. Like infantry lying in wait across a battlefield, they

sniped at each crackle and rustle as I made my way along the

trail. And then, just when I felt certain they had surrounded me,

I saw two hand-painted signs. The first confirmed my fears. It

read: "Be Cautious for Hound Dogs!" But the second replaced the

fears with delight, as it became clear that everything I'd been

told was true. It read: "The Raj House of Oudh. Entrance Strictly

Forbidden."

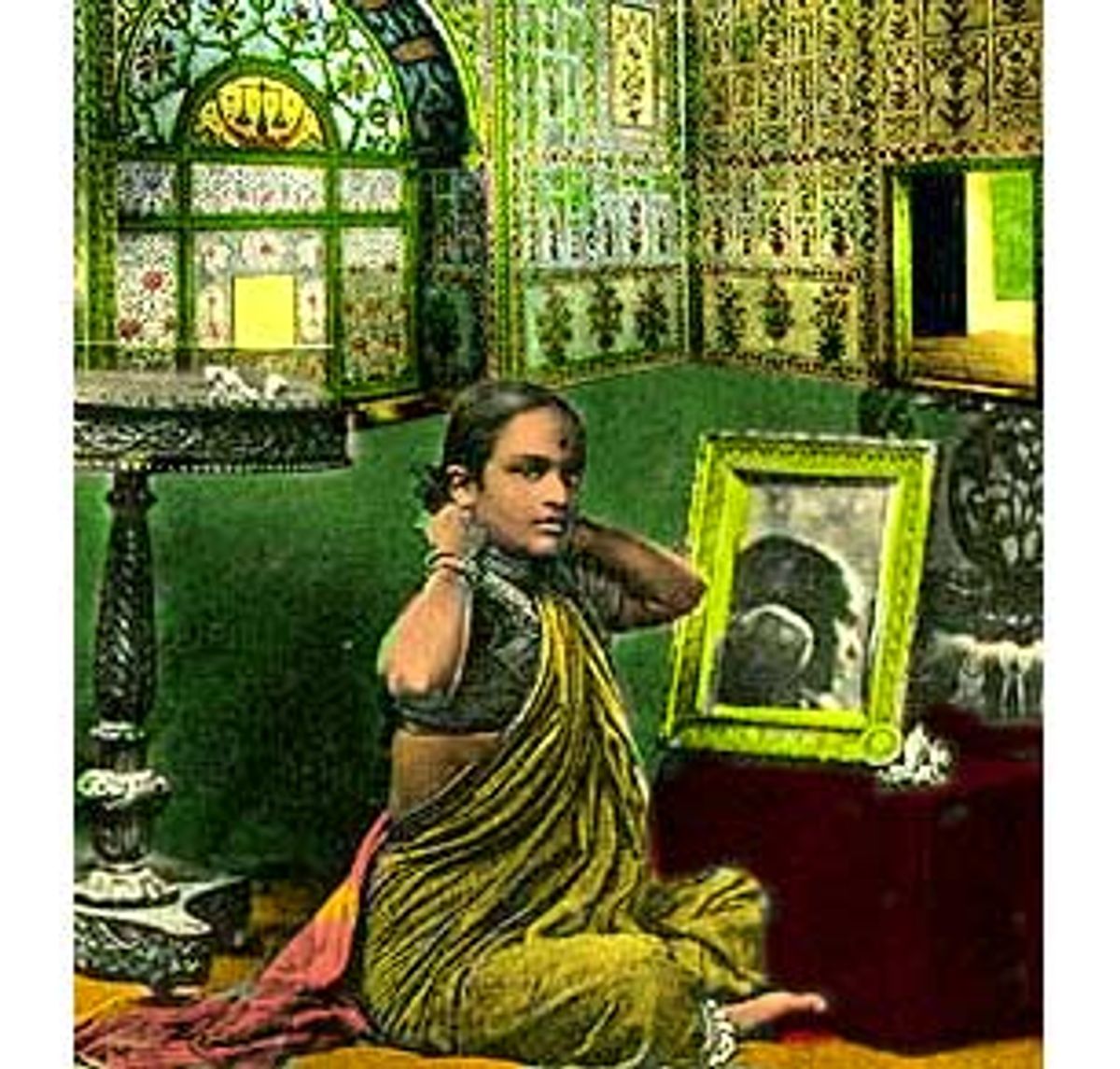

I'd first heard about the Raj House of Oudh and its self-anointed

"begum" (the Muslim word for queen) while visiting India some

years earlier. Although all Indian royal families had been

stripped of their titles in the early 1970s, Wilayat Mahal had

become a celebrity of sorts. For more than 13 years, this

great-granddaughter of the last ruler of Oudh had taken up

residence at the New Delhi Railway Station, squatting imperiously in

the VIP lounge just off Platform 1. She attributed her sparse

surroundings to a historic injustice -- a grievance stemming back

to 1856, when the British annexed the kingdom of Oudh and deposed

her ancestor, King Wajid Ali Shah. Today, like all former

princely states, Oudh is part of the Indian confederation, and

its family palaces have been converted into schools and

government offices.

Despite this harsh reality, Mahal had devoted her entire life to

preserving her aristocratic heritage. Even in her train station

home, a dark room without running water or electricity, she

reportedly sat majestically atop a raised platform, wrapped in a

black silk sari, while dictating letters to "Elizabeth" at

Buckingham Palace and India's prime minister, demanding the

return of her ancestral kingdom.

Sometime between my visits to India, the government agreed to

move Mahal, her two adult children, 12 Doberman pinschers and

five ragged servants to the old hunting lodge about 200 yards

from where I now stood. But it was the thought of her in the New

Delhi Railway Station -- pain on her face as a crackling

loudspeaker trumpeted each train arrival and departure -- that I

found so gripping. Mahal's determination to preserve the past

while testing the bounds of the present seemed to embody India's

underlying conflict. Meeting her, I suspected, would tell me more

about this land than any museum or mosque.

"Hello," I shouted toward the lodge, mindful of the warnings on

both signs. "I've come to meet the begum of Oudh. Is she home?"

There was no answer.

"Hello," I shouted again, this time trying to make my intrusion

appear more professional. "I'm a journalist. I'd like to

interview the begum. May I come up?"

My willingness to walk the remaining distance to the lodge seemed

to incite the dogs. They whimpered and jumped, knocking into one

another as they jockeyed for position behind large iron gates.

But it wasn't I who had provoked them: Someone was coming out to

greet me. Splinters of sunlight fell over the path and I could

see it was a boy, maybe 14 or 15 years old. His tunic and turban

were frayed and obviously meant for someone much bigger. When he

reached me, I noticed he wore gloves and clutched a badly

tarnished silver tray.

"I'm really sorry to bother you," I said, suddenly embarrassed by

all the honking and yelling. "Would it be possible for me to meet

Wilayat Mahal, the begum of Oudh?"

He didn't answer. Instead, he held out his silver tray and said

with authority beyond his years: "Petitions for great audience

must be in writing."

His cool demeanor made me feel I'd met him before, or perhaps it

was the thousands like him across India -- ticket agents, tour

guides, hotel clerks and bank tellers -- with the same vacant

faces. Was this an expression of good breeding or of great

boredom? I was never quite sure.

Using the boy's silver tray as a tabletop, I decided to keep my

note simple. "To Whom It May Concern. I am a journalist with an

interest in India's royal families. I would like nothing more

than to meet Wilayat Mahal and ask her some questions."

Within a few minutes, he returned with Mahal's reply. Written on

heavy parchment paper with "The Rulers of Oudh" embossed in gold

at the top, it read: "When you are unaware to whom you attend --

We do not refrain 'To Whom It May Concern.'"

Refrain? I read the note several times, trying to make sense of

it. But it was the boy's prompt departure that made Mahal's

intent painfully clear.

As I walked back to the car, I felt foolish for thinking I could

drop in on a queen, even if she didn't really have a kingdom. The

taxi driver, although happy to see I had not become dog food, was

eager to move on to a more traditional tourist stop -- after

which, I suspected, he planned to deliver me like a fatted calf

to wolfish carpet and gem merchants. For the moment, however, I

put my suspicions aside and showed him Mahal's note.

"She writes to you on paper with gold letters," he said. "To

prove you are worthy of her attention, you must seduce her."

My first reaction was to laugh. But then I began to see his

point. Right now, she had no reason to talk to me. I was neither

important nor sufficiently ingratiating.

Seduction of the queen was a task I felt oddly equipped for.

Growing up in Canada, I'd already invested hundreds of hours

pledging, saluting, toasting and singing my praises to a monarch.

By comparison, this would be a snap. Pulling out my pad and pen,

I began crafting another letter. This time, I thoroughly greased

the page with words I imagined would make any royal positively

weak-kneed.

"As you are the head of one of India's oldest royal houses and

greatest kingdoms, I humbly request one hour of your time," I

began. As a further inducement, I asked the driver to take me to

nearby Malcha Market, where I had the letter typed.

Later, when the same boy answered my call, I couldn't resist

bowing slightly before setting the crisp, white page upon his

tray. Then I waited. For more than two hours I stood staring at

the old lodge, trying to imagine what the queen's life must be

like behind its crumbling facade. A little more than a century

earlier, Mahal's great-grandfather had lived in a magnificent

palace, surrounded by beautiful courtesans, artists and

musicians. Perhaps that's what provoked the British annexation in

the first place. Oudh was a kingdom in pursuit of sensual

pleasures, not sensible ones. Across Asia, it had become renowned

for dance and poetry, for opium and exotic perfumes, and for

growing the best roses. But Mahal's forest lodge had no gardens.

Her servants had to bicycle a half-mile just to fetch water for

tea. This was a dismal and decrepit place, in which the Kingdom

of Oudh lived on solely in her imagination.

When the boy returned again, he carried two large sheets of

paper. As before, the message was cryptic. "We demand no sympathy

this regal class of ours," the first page began. "Clinging to the

past we may be crushed. The spider web intrigues against the

Royal House of Oudh. We are paying the debt of nature and trust

to the natural defenses." Her words were like riddles, revealing

everything and nothing at the same time. Then I reached the last

two lines, and my heart sank. "You have been commended an

interview Nov. 26 at 3:30 p.m. sharp. If yes, inform the bearer."

"Nov. 26?" I said, unable to conceal my emotions. "That's in two

weeks. I'm leaving India tomorrow morning."

Without a word, the boy turned and walked away. I wanted to go

after him, to stop him from delivering this final message, but

all I could do was move a few steps closer to the old lodge and

wonder about the curious lives of its inhabitants.

When I got back to the taxi, the driver made no inquiries about

my last trip into the woods. Instead, he turned the key in the

ignition and began navigating his taxi along the narrow road

leading out of the forest.

"Now, I will take you to the Birla Temple," he said.

Shares