Turning to a book of stories about ex-lovers, you might ask yourself what you want from stories about ex-lovers. A wailing country song or a Latin revenge scenario are good places to start, but it's also understandable if you want an exorcism -- what Frank Sinatra could have used when he moaned to his pack, "Ava! Why can't I get this girl out of my plasma!?"

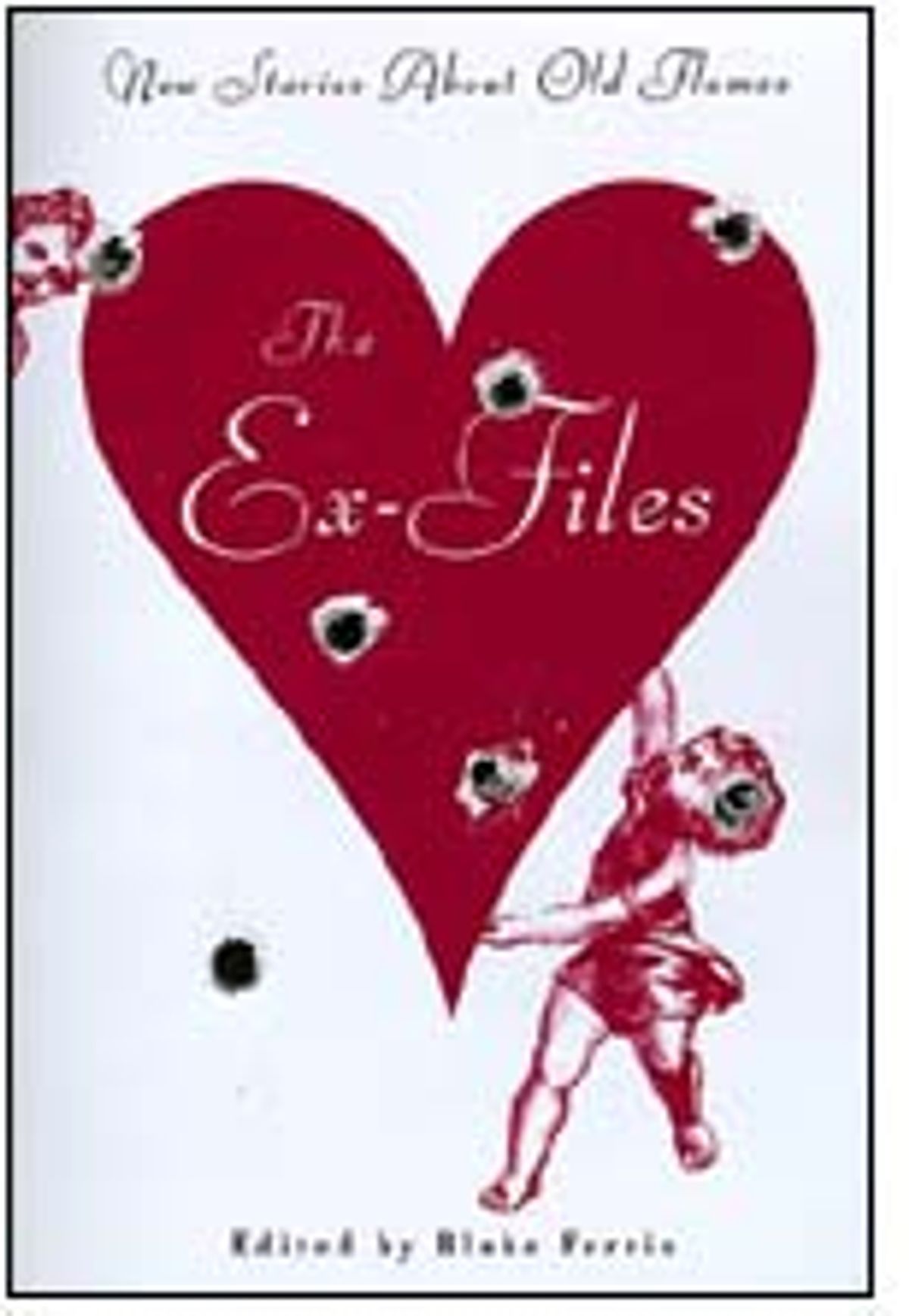

In "The Ex-Files," editor Blake Ferris has assembled what must be history's

first anthology of screeds and homilies to former boy and girlfriends. It's a

book rich with tenacious, if fictional, Avas. These creatures have inspired no less than Dorothy Allison, David Foster Wallace and Junot Diaz. But strange to say, by the end of the collection it still may not be entirely clear who counts as an "ex." Maybe that's why they're hard to forget; they're hard to identify.

|

Wallace's story "B.I. #20 12-96 New Haven CT" -- from his 1999 book

"Brief Interviews with Hideous Men" -- is a twisted monologue by a woman-hater, a

deposition thick with intelligence and contempt. But he ends his diatribe

softly, even stupidly. "Why did it matter if she was fluffy or not terribly

bright?" asks the hideous speaker. "She had all my attention. Happy now? All

borne out? I knew I loved. End of story." The sense of an ending, an end point, that achieving romantic love represents -- and the fierce struggle to resist getting there -- gives several of the stories a thriller-like pacing.

In Jennifer Egan's "Forty-Minute Lunch," a

journalist assigned to profile a teenage starlet probes cravenly for revealing details

for his story. Getting none, he forces the girl to the ground, landing himself

behind bars. Similarly, in Derrick Jensen's "Honeybees," animal rights terrorism nearly overwhelms the love story. The mood is more suspenseful than wistful.

But there are sweeter stories, too. Most notably, Amy Sohn's "I've Done This

Before." Here, as elsewhere, Sohn creates a heroine who crashes into one body- and soul-busting sexual situation after another. But, though she tries, she can't quite take this roughness in stride. She talks tough, generalizing about "every jerky guy

who'd ever fucked me over" and boasting: "I was bold and

aggressive and not afraid to come on to men I wanted." But as the story winds

on it becomes clear that she's missing something nameless, and it's not just love -- there's something

inaccurate or under-thought about what she claims to find routine. When she finally tells her new boyfriend, "I've already had sex doggie-style in this skirt," it's not a

comic or even a crass line, but something like a war-time understatement; you get the sense that these two people don't really know how they got into this skirt, this bed, this jam. It's a strangely lovely story.

In the end, however, as good as some of these stories are, ex-lovers aren't a great organizing principle for an anthology. As these writers represent them, exes make up a formless population, a shadowy, vaguely criminal set. What's meant to unify the stories is their common cultural source: what Ferris identifies in the introduction as the relatively recent norm of serial monogamy.

This love 'em and leave 'em jungle spares no one. As Ferris puts it matter-of-factly, "If you don't have at least a few notches in your lipstick case, you're a loser." It's not so much unforgettable characters that generate tension for these authors, but a bind. Call it the need for notches, and the parallel dream of the Final Notch.

It's clear from these stories that the rocky road back to the ex is, in a narrative, exhausting. Writing about a former lover may work better in lyric poetry, in which repetition and cycling back are intrinsic. In a recent poem, English poet laureate Craig Raine gave his reasons for memorializing a dead girlfriend. Why does he write of her, when she is troublesome, sick, gone? "To make you hear," he writes. "To make you here."

Shares