"We asked for cheap," Ann said. "Economico." The man shook his head. Even for Cuba this car was a bomb. A bomb that we'd waited four hours to get, arriving at 7 a.m. in Havana and hoping there'd be a car to rent that day. Now here we were in Santiago de Cuba on the other side of the island after six days of battle with the bomb, whom we'd affectionately named Franqui early on in the hopes of endearing it to us. We feared for our deposit. "The engine runs OK," I told the man, "we made it all the way from Havana. It's just everything around it that's crumbling."

I had come to Cuba to discover the island on the millennium. Literally, but also metaphorically. What was Cuba to become in this new century? We spent the first two weeks in Havana before our odyssey with Franqui, and by then I had established a routine much like any I have at home. I rose at around 6 a.m. and drank cafi con leche at a nearby cafeteria on the corner of Avenida 23 and Calle L in Havana -- one of the city's main intersections and home to Coppelia, the famous ice cream metropolis where Cubans line up for hours every day.

In those early mornings I strolled past the woman selling ham-and-cheese sandwiches or cigarettes, depending on what was available that day; past the tiny shooting booth where kids and adults re-created the Revolution; and by my final morning, when Franqui was just a bad but cherished memory, the "Save Elian" poster with his primary school picture faded to white.

The waiters at the cafeteria came to recognize me, one of them shouting "la periodista" when I walked through the door -- the journalist. For months leading up to this trip I had imagined myself prey to the deep and unabashed love that writers for centuries plummet into upon stepping onto Cuban shores. I saw Havana's sultry streets, salsa, rum, cigars, sexy women and amorous men; I imagined dancing till dawn and languid days in the sun with a population of idealist albeit somewhat disgruntled citizens. I thought of religious Santeria rituals and discussions of ideology. What better reason to visit a forbidden place than romantic longing for that which you have been denied? The proverbial apple. The problem with the apple theory, however, is that once you begin, the rest is left for you to finish -- core, seeds, bruises and all.

Asking Cubans what Cuba at the millennium means is a bit like trying to ask a 12-year-old to dismantle the engine of a Toyota. It's not so much that it can't be done -- more that no one really wants to try. In the U.S. we are forever asking who will follow Fidel Castro. Who will be Cuba's next president? What we are really asking is when will those darned Cubans come around to our capitalistic way of thinking? As one 25-year-old said to me, "Politicians all over the world are the same. Fidel is not bad or good. He is Fidel. The important thing is that I work and eat." This was his millennial Cuba. Work to eat. Eat to work. One century same as another. Or, to put a finer point on it, it's not what you drive, but how you keep it on the road.

Visiting Havana, many write, is like going back four decades. Our best example of an anachronistic city. Old American cars enigmatically still running punctuate the winding, cobblestone streets of Old Havana. Once-grand mansions of the '40s and '50s with intricate latticework and crystal chandeliers contain many of the same antiques they contained when their owners fled after the 1959 revolution. Couples along the Malecon walk by the sea amid tourists and prostitutes -- much like they did when the Mafia controlled Havana's economy midcentury. The embargo, many speculate, has done more to keep Castro's minions cheering for him than any other contrivance in Cuba's recent history. If the economy is poor in Cuba's post-Russia era, the blame can be pointed directly northward, Castro says. El bloqueo.

But those who speak of anachronism miss the point. The truth is that Fidel's millennial Cuba is as much in the throes of a new revolution as it was in 1958. This one, however, is more subtle, and more immutable.

Franqui's troubles were not apparent at first. Cars are difficult to rent in Cuba and reservations are nonexistent, so when we were presented with this red, shiny tot of a car for 40 bucks a day, we were overjoyed. No matter that I couldn't see over bicyclists as I drove. There's not much traffic anyway once you're out of the cities. Ann and I sputtered out of the Transtur office hailing Franqui as our ally in travel and, after loading him up with backpacks and 30 liters of black market gasoline and a siphon hose bought via the owner of our guest house, we were off.

Our plan was simple: Cienfuegos, Trinidad, Santa Clara, Camaguey and either back to Havana or on to Santiago de Cuba, where we'd fly back to Havana. With Franqui, the island stood as an open invitation.

But as is true with stories, life and cars, it is the details in Cuba that matter. It's not that the American Fords and Russian Ladas are kept running, it's how they're kept running: through sheer determination, ingenuity and perhaps a little prayer -- all things we would come to understand about Cuba via Franqui.

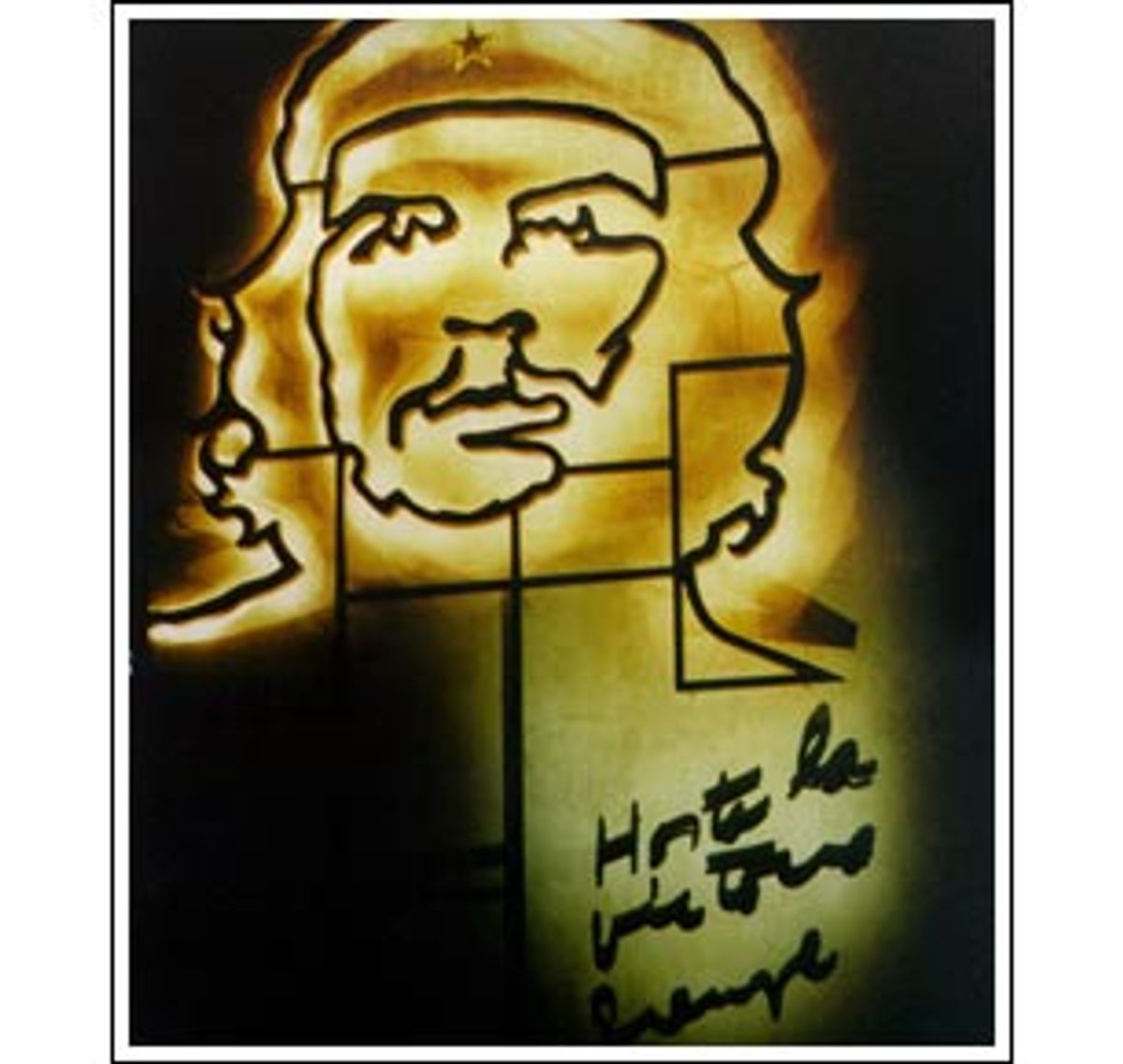

There is a certain sadness to Fidel's failed Revolution. After all, the ideas that he, Che Guevara and Camilo Cienfuegos (Guevara's counterpart in eastern Cuba) had were good and true: men working for the sake of the work, men working unselfishly for one another, all having equal opportunities, equal paychecks, equal goods. At some level, Fidel must be forgiven because the failure cannot be attributed solely to him. Socialism is flawed because humans do not possess the same passions and priorities, not because madmen stand at its helm. To have socialism today you'd have to block out the world and even Castro can't do that.

So when the world comes in, I wanted to know, how do people stave off their anger? One Cuban who worked at a luxury hotel near Santiago refused to eat from the deluxe buffet offered to tourists, despite it being included in his wages; he could not enjoy that which his family was denied. When the woman serving spoonfuls of beef dishes on platter after platter to those tourists goes home to a kitchen of canned meat and six eggs per month, how does she control her rage?

In spite of Castro's efforts, Cuba today is a two-tiered society, though the haves have less and the have-nots have more than could be said of Batista's Cuba, which the United States supported through much of the '50s. Those with American dollars have cars. They may be 20-year-old Russian clunkers with missing door panels, loose floorboards and taped windows, but they aren't motorcycles or bicycles or buses like the have-nots. Soap, gasoline, food, medicine -- all things rationed are often available with U.S. dollars. The irony that his country runs on the monetary unit of his most scorned enemy must surely drive President Castro mad. But Cubans --presidents and peasants alike -- seem to have discovered their own methods of survival long ago.

Our first stop with Franqui was in Cienfuegos, roughly a three-hour drive from Havana. We made it by midafternoon, rejoicing in the sun and sand. We'd taken the Autopista, an enormous highway that runs through much of Cuba which, if there were lane markers, would be roughly eight-lanes wide. Since it is not a land of cars, we saw few along the way and dozens of folks flagged us as we chugged past. Of course Franqui, roughly the size of a large novel, was filled to capacity and we couldn't pick up any stragglers. This was to be our only day free of Franqui anxiety.

The actual millennium here was largely recognized to be next year, and no matter anyway since New Year's -- another century forthcoming or not -- is a family affair and not the debaucherous fiesta of the States. Relatives eat, drink, dance and open small gifts from each other.

Before departing on our journey, we had spent a wonderful evening with a family in Santa Fe, a suburb west of Havana, eating roast pork, yucca and congris -- Cuba's national dish of rice and beans. One of the guests cut sprigs of bougainvillea for us so we'd not feel left out as they opened gifts. Not a single person uttered Y2K. The hysteria that gripped the U.S. seemed to have escaped Cuba entirely. Indeed, one man said in disbelief: "I heard the Americans were buying water and taking money from their banks!" When I confirmed this rumor, he howled.

But Castro's original Revolution deserves some credit. When he took power in 1959 he outlawed racism. While surely it exists still in hearts, and blacks are often targeted as perpetrators of petty crimes, this younger generation of Cubans seems generally to have embraced Castro's view. Interracial couples are as common as their homogenized counterparts. There is no minority housing in any of the towns we visited. Indeed, even when Castro came to the United Nations shortly after he took power, he made a point of staying in a Harlem hotel. Certainly it may have been a show, as many journalists have declared over the years, but show me an American politician who's done likewise.

Even more importantly, Castro's legacy, above all others, will be that he returned to the Cuban people a notion that they could control their own destinies, a sense of pride and nationalism. For hundreds of years they'd been colonized and oppressed by the Spaniards.

Castro, who began his revolution with only a dozen or so men and seemed to have been initially inspired by the Keystone Cops, proved that there is strength in dreams -- 1959 was the first year of Cuban independence. "Our future task," Guevara wrote at the time, is that "the concept of their own strength should return to the Cuban people, and that they achieve absolute assurance that their individual rights, guaranteed by the Constitution, are their dearest treasure." If, in the year 2000, Castro remains angry, it is anger that he cannot change Cuba's history of colonization in the way that he changed its future in 1959.

Now, the thing with Franqui is this: I believe he was inhabited by spirits. A little Santeria, perhaps? It's not so much that he broke down again and again, but that he offered an infinite number of obstacles in our path after that first day. From Cienfuegos we drove to Trinidad, a small colonial town with cobblestone streets (which Franqui disliked) and brightly painted buildings. It was declared a World Heritage site by UNESCO in 1988 and funds have been used to restore it. Since cars are fairly rare and car parts close to extinct, you pretty much have to pay someone to watch your rental car at night. No problem since this costs a buck or two and the man we hired directed me to park two inches from the wall, being careful to pull Franqui's mirror in beforehand.

It wasn't until the middle of the night that I bolted upright with this epiphany: How would I get inside Franqui to pull him out? After all, the only keyhole was on the driver's side, now only centimeters from a brick wall. Ann and I labored over this reality. Climb over the hood and unlock it? I still couldn't get inside. Push it? How to put the car in neutral? Pick it up and move it? In the morning I pointed out my stupidity to our parking attendant, who merely called over another man and the two of them yanked Franqui's rear as if it was made of cotton and we were on our way. For the moment.

In minutes Franqui began bucking and I knew we were in trouble. The gas gauge read half a tank. It seemed to be the fuel line and we miraculously made it to the local Transtur office where we were told there were no cars to rent. Not in Trinidad. Not in Cienfuegos. Not even in Camaguey. All we could do was drive to the Transtur mechanic 10 kilometers away and hope for the best.

We stopped and started Franqui, praying and cursing and wanting the blazing sun to disappear behind a cloud. The drive took nearly an hour, and after six kilometers it seemed Franqui had had enough. We were horrified at first that we'd have to get out and push, but then we realized the rat only weighed six pounds. Off we went.

It took the mechanic 15 minutes to determine that Franqui's half-full gas gauge actually meant empty and not only had we run out of gas and pushed the rebellious tot, but we had done so with 30 liters of gas in the trunk. To his credit, the mechanic merely grinned.

After a wasted day, we drove back to Trinidad, back to the parking wall with the passenger side hedged in this time and relief that the worst was behind us. Our faithful attendant greeted us smiling and, seconds later, pointed to our flat back tire.

Shares