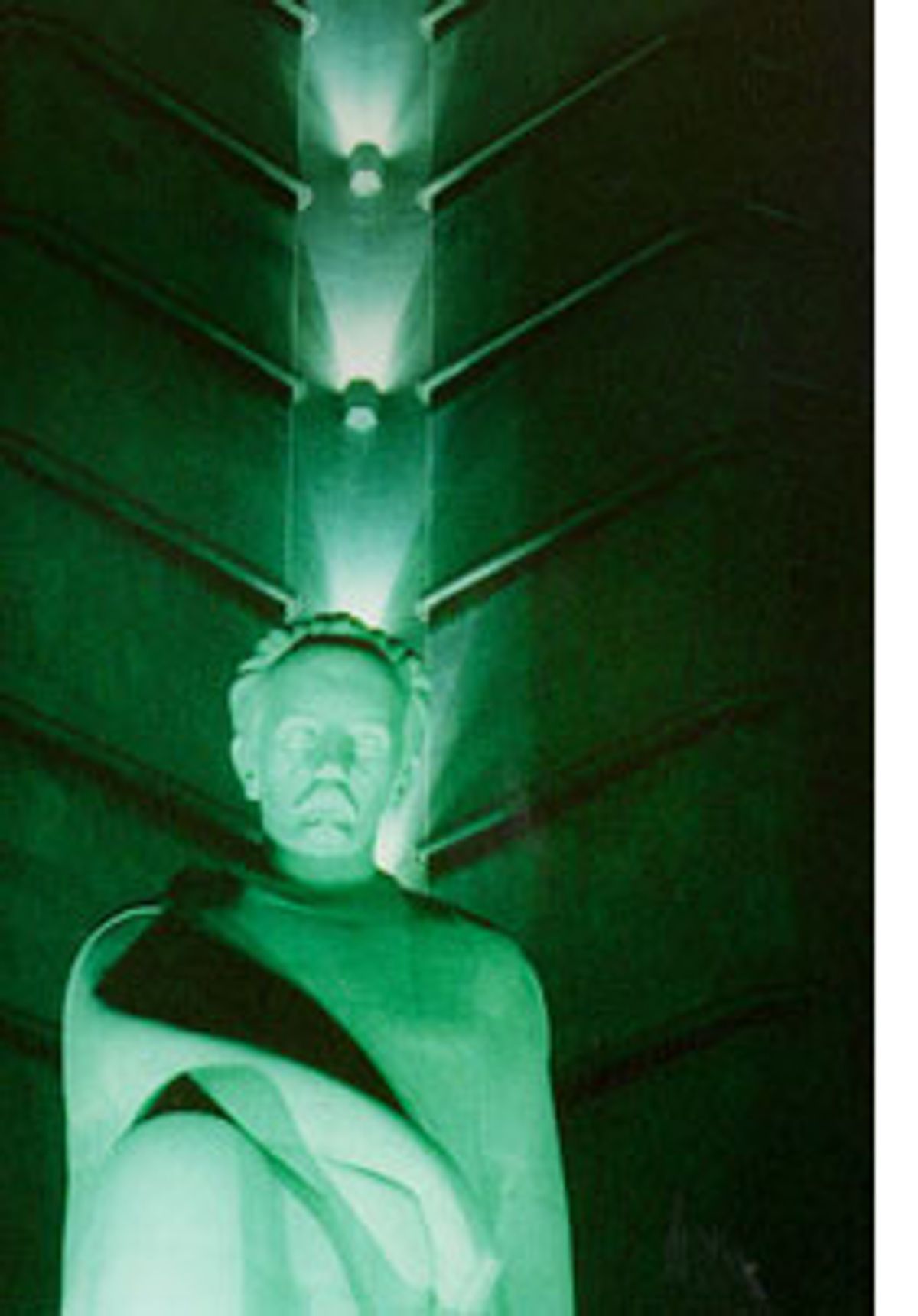

Here is the truth: Before I came to Cuba I loved

Fidel Castro. And still do, a little, in the way

that you love an ex who once seemed so right for

you. It's not a romantic, yearning-in-the-loins

love, but an idealistic respect for someone with

the gall to think he could change an entire country

and the ability to succeed.

It wasn't falling in love with Castro or Cuba that

surprised me; I knew before I left Chicago that it

would be a place that would speak to me, a place

where passion wouldn't be a thing defined only in

bedrooms and whispers, but a place where I'd get my

color back, make my vision a little sharper. I need

that every now and then. Like Samson and his hair,

travel's where I get my strength. What did surprise

me was how separate Castro came to be when I spoke

of Cuba, like understanding that Vietnam is so much

more than the setting of America's biggest 20th

century blunder.

The latest U.S.-Castro muscling over Elian

Gonzalez is a case in point, the best

example of what Fidel's done for Cubans. U.S. media

shows the 50,000-plus demonstrators in Havana to

bring Elian back home. Indeed, billboards

and posters with a confused looking Elian

punctuate the city declaring Devuelvan a

Elian a su Patria -- return Elian to

his native country. Thousands of similar T-shirts

are passed out. It is government-perpetuated,

declares the United States, which is meant to

somehow render it devoid of meaning.

Indeed, like many events in Cuba, the Elian

protests appear to be, in part, cause for

socializing as much as anything. At one of the

events I saw, groups of blue-clad security men sat

amid the protesters, chatting and eating peanuts

from funneled pieces of paper. The speakers evoked

rage at the situation, but wandering through the

masses felt a lot like a walk through a summer

festival -- not because conviction here was less

than total, but because this is Cuba.

So begins the new Revolution. Each Cuban with

dollars is a budding entrepreneur, an independent

capitalist. Throughout our first week here, Ann and

I commented on those strange gas fumes emitted from

each car we rode in. Then we learned that the

employees of state-run gas stations skim off the

top and resell the gas on the black market for

U.S. dollars, which the car owners, or renters,

keep to siphon from small jugs in their trunks.

Same with cigars. And soap. And food. And shoes.

Anything for sale anywhere -- tools, stereos,

cassettes, refrigerators -- nearly all is available

on the street to those with dollars. And since

rations only cover the average Cuban for two weeks,

such grand-scale thievery is tolerated. Franqui,

our sputtering Subaru, initiated us into this

system.

This is not to suggest Cuba is a rich economy --

there isn't all that much to buy. I searched in

Havana for days for a banana and finally gave up.

Bottled water, very expensive in Cuba, is more

prevalent in remote areas of Tibet and Cambodia.

Public transportation is the worst I've seen

anywhere. Cars are few and buses fewer.

There is a free farmer's market now, following

Castro's reforms in 1994, but it is expensive even

for foreigners. Beef is saved for tourists and

pregnant women. Each Cuban gets roughly six eggs a

month, but omelets are plentiful in hotels. Toilet

paper is rare, even in hotels, and most households

use newspaper or magazines. Taxis have become the

domain of those wealthy enough to own cars. To get

a ride, one need only wave an arm and Juan Q.

Public will pull over and take you anywhere within

the city for a few dollars, offered inside the car

while the police look the other way. One man in

Cienfuegos even took us on his horse and buggy down

a labyrinth of side streets to avoid the police.

For $2.

My Cuban friend Leonardo, who spent time in the

States, told me that he did not live in so

repressive a society as I might think. We were

driving to Havana from the new Josi Marti airport,

built last year. I did not answer, but sat smugly

in the back of his gasoline-smelling car and

thought he didn't really know oppression because

he'd never really known freedom. But slowly, over

the course of my weeks in Cuba, I began to see that

it was I who'd been wrong.

It began with Leonardo telling us about when he was

a ballot counter during the 1996 elections. (Since

1992, elections have been held every two years for

the General Assembly, which includes Castro.) When

he saw people write "Down with Fidel" on ballot

cards and suffer no consequences, he virtually

stopped living in fear -- overnight. There are four

daily papers in Cuba, he said, and it is up to

journalists to exercise freedom of

speech, though what sorts of pressures they may

feel he couldn't speculate. But freedom of speech

-- like station attendants selling gasoline, farmers owning land and

families who turn their living rooms into

restaurants and their bedrooms into guest housing

-- is the foundation of this new revolution. Tiny

steps toward capitalism.

We had decided to avoid Franqui's flat tire until

the morning and though the lugnuts gave us quite a

challenge, the parking attendant's son and neighbor

replaced the old tire with the spare in no time. We

gave them a few dollars, thanked them profusely

and, at Ann's wise urging, drove back to the

Transtur mechanics to have our spare patched up.

Happily, it seemed they had little to do until our

arrival with Franqui. While they fixed the

spare, we explained about the gas gauge being

broken and they took to fixing that, too. Then they

fixed a missing part on the door panel. Then they

cleaned the windows. And when we asked if Franqui

could make it to Santiago they all smiled and said:

No problema. Several hours later we were on our way

again, this time absolutely confident that we had

treated Franqui well and would be duly rewarded

with faithful service hereafter.

The loud POP came halfway between Trinidad and

Camaguey, amid soft fields of sugar cane with the

Escambray mountain range behind us and palm trees

punctuating the fields. My heart raced remembering

the difficult lug nuts of the morning. This was no

mere flat. A 4-inch slice through the tire exposed

the metal threads once holding it

together.

There wasn't a car in sight. I said a silent prayer,

jumped on the tire iron and miraculously the

lugnuts budged. We managed to change the tire -- me

thanking Ann for forcing us to get that spare fixed

-- and drove to a shop in Bayamo at the foot of the

Sierra Maestra mountain range to buy a spare. The

shop, of course, was a man with four tools and a

sign hanging outside his house. When it was

determined that no spare could be found in the

whole town, nor any surrounding towns, nor probably

the whole eastern portion of the island, the man

sewed the wrecked tire together with plastic

thread, ironing sheets of rubber over the inside

and eventually salvaging the unsalvageable. This,

as much as anything, symbolizes the unwavering

fortitude of four decades with Fidel and cast.

Cuba is no Utopia, certainly, and daily we were

reminded of the dichotomies inherent in the country. Money

does not hold the power that it does in the United

States since it cannot always purchase what you

need. One man told me he'd been offered U.S.

$40,000 for his house by a Dutch man, but he'd

turned it down. "What would I do with that money?"

he'd said. "Houses are harder to get than money."

He'd seen the wealth in the United States. He'd

seen all that money could buy, all that he lives

without. But then he'd seen the poverty in Haiti

and Jamaica. "They eat garbage," he said. "They

live like dogs."

Tourism, of course, is Cuba's main economy. And for

the socially conscious traveler, Cuba is one place

where your dollars can go directly into the hands

of the people and not the government. This happens

when tourists avoid large hotels, that are

visible at night because they are in the part of

town with the most electricity. In fact, if you

stand in La Cabana, the old Spanish fortress across

the bay from Havana where Che Guevara set up shop

after the '59 triumph, you can chart the tourist

areas of town -- they are the sections with the

most light. The rest of Havana is dark and still.

But this new Revolution is slower in the

countryside. In the week we drove Franqui through

the island, it took us several days to realize that

the posters and billboards with Elian's

visage began to disappear, as did many of the Cuban

flags hanging from windows, and posters of Camilo

Cienfuegos began to replace those of Fidel. Occasionally the

old "Socialism or Death" slogans appeared on walls,

though they had been virtually erased from Havana,

and the hustlers that Havana police strive to keep

away from tourists seemed to multiply tenfold in

Trinidad and Camaguey.

Halfway through the drive to Santiago I discovered that

instead of being fixed, Franqui's gas gauge was now

stuck on full. I began counting kilometers.

The equation between what you think you know and

what you come to learn in Cuba never evens out.

There is always more to discover because the rules

are liquid; what you read rarely matches what you

see. Property, for example. Cubans are not allowed

to own their own houses -- on paper, at least. But

if they want to buy, say, the roof from a man in a

one-story house, they can build up from there,

someday having a roof of their own to sell. One

large three-bedroom apartment we visited in

Santiago had cost U.S. $7,500 to build with

materials all purchased one by one on the black

market. This week, a toilet. Next month, maybe a

sink. It's the ratio of available capital to

available material, and the laws of supply and

demand are not applicable in Cuba. Yet.

The man who fixed our tire in Bayamo ordered us to

toss the thing immediately upon arriving in

Santiago. After three hours at the shop, we were on

our way with 74 miles to go. I drove gingerly

over potholes and train tracks, white-knuckling the

steering wheel and imagining how we'd get Franqui

through the mountains and into Santiago if another

tire blew.

When we finally drove into the city after sundown,

our hearts melted with relief and we fell

immediately in love with Santiago's winding streets

and hills, which reminded us of San Francisco. We

pulled up to a guest house that had been

recommended and were greeted enthusiastically in

English by a young woman who seemed to come

factory-made with a smile. We left the car out

front temporarily, with the hazards on. Relaxing

for a moment in the open courtyard of her house,

Ann and I grinned at each other. We all -- even

Franqui -- had made it, had reached a kind of

promised land.

"Better not leave Franqui out there," I told Ann,

"with the keys inside."

Her face dropped. Turned white. "The keys?" she

said.

Indeed. I'd left them in the car. She'd locked it.

And there it stood, flashers going like

admonishments that we would never be free of

Franqui's spirit. The woman in the guest house

smiled nervously, telling us perhaps her husband

could help if he got home soon. We shook our heads

at our misfortune. How could the gods betray us so?

A man in a car happened by and greeted us;

our new hostess told him briefly of our plight,

asking if he could possibly help. He nodded at the

car, studied it for a moment, then plucked his own

car keys from his pocket, stuck one in Franqui's

single keyhole and voil`, the car was

unlocked. "SOY CUBA!" we shouted in unison, I am

Cuba! Franqui would not conquer us!

Most Cubans agree that changes are needed for

survival -- 1993 was an awful year, with people

starving in the streets after the fall of Russia.

But things are better now. More goods are being

bought and sold and everyone has a home. Indeed,

wandering the night streets of Havana, Cienfuegos,

Camaguey, Trinidad and Santiago, I came across only

one homeless person. Too many changes at once will

bring on a collapse like in Russia, many fear. And

though Fidel waves these as perpetual banners, free

health care and education are banners worth

waving.

If there is one thing that unites Cubans, beyond

Elian fervor, it is a collective hatred of

Miami Cubans. Fidel may be bad, but the Cubans in

Miami are worse, everyone says. An infiltration of

those in Florida, many fear, would bring tides of

crime, drugs and poverty -- all the debauchery

Miami is infamous for. The Miami Mafioso, the Cuban

population there is called. And Cuba would return

to its pre-Castro days with the mob running

high-stakes gambling and overpriced sex shows.

Only this time things would be worse because those

in Miami have more money. Fidel, at least, is a

known commodity.

Though their fears are not unfounded, neither set

of Cubans bracketing the Florida straits is

offered a proper perspective. The stereotypes are

pervasive: Miami is gangs, drugs and murder whereas

Cuba is only prostitution and petty thievery.

As for the U.S. embargo, Cubans have at least one

reason to rejoice: It has probably saved the island

from the inevitable death-by-tourism plaguing Bali,

Cancun, Jamaica, Bermuda and countless other

"tropical paradises." There is a down-home warmth

to the place, like the house of a favorite cousin.

The police are numerous, but friendly, and greet

you as you pass. Talk to a Cuban for more than 10

minutes and you'll be invited home, provided you

convince the police that you're not being hustled.

It's a place where human noise, which is constant

and loud, offers a sense that life is happening all

around you. Not machinery, but the voices of

community.

Within our first 10 days in Havana we knew our

neighbors and the brother of our guest house's

owner, and his son's girlfriend, and the father's

doctor and the neighbor's friends. Three times I

ran into people I'd met, as if Havana was some

small town I'd grown up in and not just a place I

was visiting. It is the frenzied, frenetic rhythm

of a salsa song with pauses long enough to catch

your breath and dance again. It is the broken

instrument held together just barely, sounding

nearly as it always has, a little rough around the

edges and painted in pastels, but still playing.

Not unlike Franqui, the little devil that did, in

the end, bring us where we wanted to go. Franqui

hadn't brought us in the way we expected, and not

in the ways we know or could have imagined. But all

along the way people had aided his and our

survival, given their time, material and skill with

a patience that only comes from years of making do

with what you're given: eating, as it were, the

whole apple. Franqui, his skin bruised but core

intact, had made it nonetheless.

Shares