It's getting harder and harder to miss Shmuley Boteach, the ultra-Orthodox rabbi who's going around calling himself the "Love Prophet" and preaching relationship advice worthy, he believes, of the Old Testament.

The media can't resist this fast-talking rabbi with his string of one-liners on everyone's favorite subject. Recently, on tour for his characteristically kitschy new book, "Dating Secrets of the Ten Commandments," he has debated pornography with Larry Flynt on Judith Regan's talk show and bantered with TV hosts Matt Lauer and Charlie Gibson. He has made the rounds of the network morning shows giving dating advice to singles, and he obliged Time magazine with romantic tips for Monica Lewinsky. He has shown up at a popular Manhattan synagogue with pal Michael Jackson in tow and appeared on Howard Stern's radio show making sympathetic noises the day after the host announced he was splitsville with his long-suffering wife. New York magazine reports that he's even about to launch an online dating service called LoveProphet.com. Topper: Jay Leno handed a copy of Boteach's relationship book to Dennis Rodman when he and Carmen Electra hit the skids.

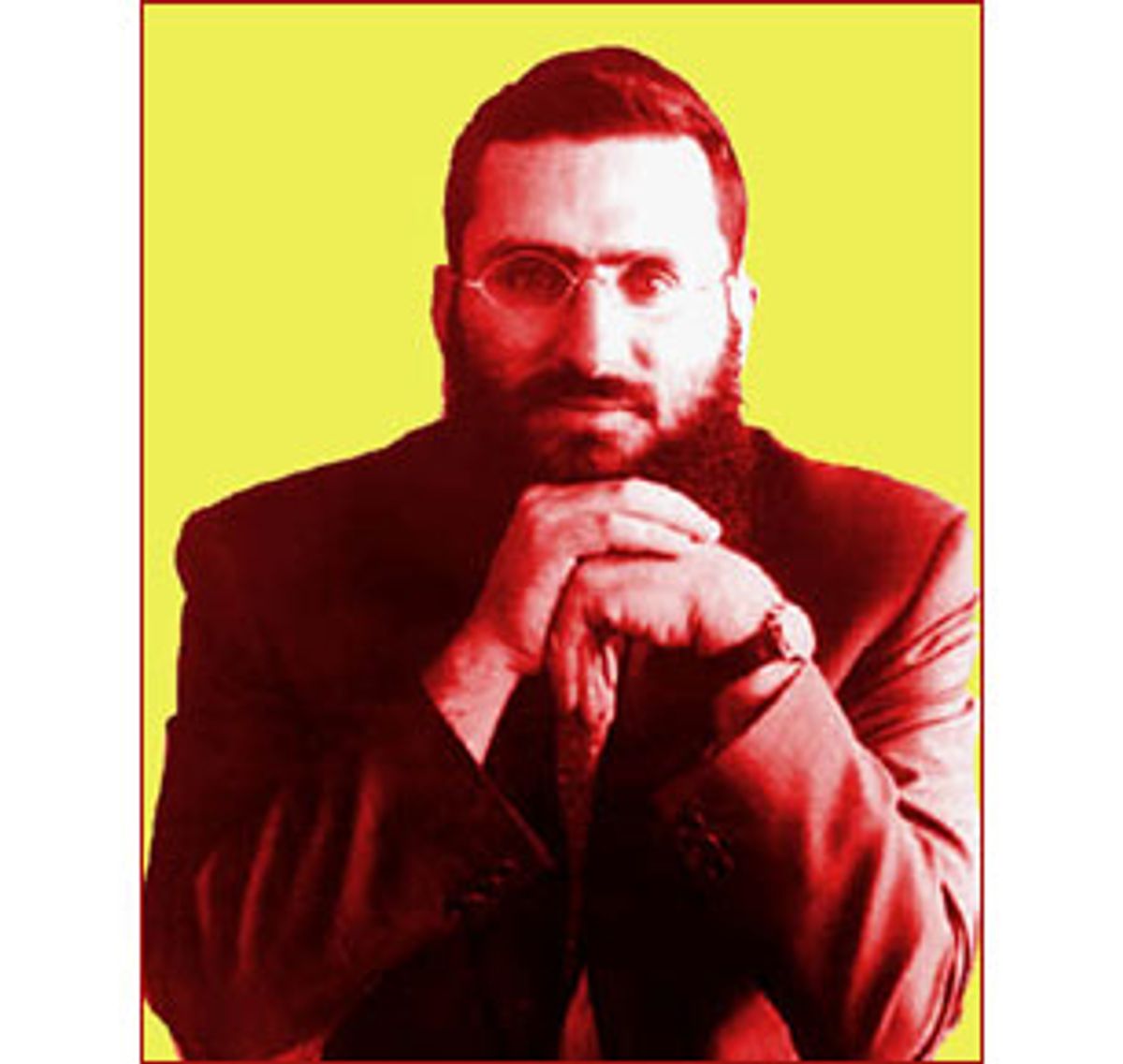

Boteach is immediately recognizable, with his full beard, intense blue eyes and black yarmulke. He's also known for his corny humor, polished last year in his bestseller "Kosher Sex," and the way he's always elbowing for the spotlight. (In recent press releases he has bestowed his "blessing" on oral sex, the film "American Beauty" and attending synagogue.) Mainly, however, he has made his name introducing Jewish "relationship values" to a worldwide audience ("Kosher Sex" was translated into 10 languages), emanating a kind of '60s-style version of universal love in an Orthodox Jewish context.

Sound like a contradiction? In many ways Boteach is. In his personal life, Shmuley, as he likes to be called (it's a diminutive, like Bobby or Mikey), follows Jewish law to the letter and believes that this path -- in all its rigor -- is "the truth for the Jew." On the other hand, he has made a career of reaching out to the nonreligious, Jews and non-Jews alike, who are part of a new wave of seekers looking for tradition and a more spiritual life.

For 11 years at Oxford, as outspoken director of the L'Chaim (as in "Drink up!") Society, Boteach built the second-largest student organization in the history of the strait-laced university. L'Chaim created a come-as-you-are Jewish environment to which students (more than half of them not Jewish) flocked. They came for the scraps of wisdom delivered by Boteach and a legion of celebrity guests (Mikhail Gorbachev, Boy George, Stephen Hawking, among them) speaking on spiritual and religious themes. But mostly they came knowing that they could open their hearts to relationship guru Rabbi Boteach and he would give them nonjudgmental religious advice. (According to Boteach, at Oxford hundreds of non-Jews asked him to convert them to Judaism as well.)

"I have seen my purpose as bringing godliness to places it has never reached," Boteach said, explaining his universalist message "to bring values and godly teaching to the widest possible public, Jew and non-Jews included."

That openness has made Boteach's public career, transforming him, at age 33, from an author of little-read books on Judaica into the spokesman for a universally accessible Judaism. But with his quick tongue and warm spirituality, he has also lost his place in the Orthodox communities that fostered him. Lubavitch, the ultra-Orthodox community that educated and ordained him, balked at his outreach to non-Jews and severed the relationship in the mid-1990s. Then, with the hoopla around "Kosher Sex," published in England in 1998, the conservative British rabbinical establishment accused Boteach of dishonoring his office with his public sex talk; in May 1998, he resigned his synagogue pulpit there. Now, with a new book under his arm and a fledgling chapter of L'Chaim in New York, Boteach is starting anew in the kind of city that can match his brassy ambition.

There is something refreshing about Boteach's willingness to throw some color onto the black-suited, buttoned-up mores of the Jewish establishment. "One of the reasons so many Jews view Judaism as insipid and oppressive," he says with typical bravado, "is that there isn't any inspiring leadership." But as Boteach frankly admits, his efforts are part sincere, part shtick, a song-and-dance routine that will pull in the audience. That's what nabbed him a huge following at Oxford. And that's what gave him instant access to the American media. According to L'Chaim's mission statement, "We regularly host world leaders lecturing to young, impressionable audiences on the values that underpin Western civilization."

Celebrity speakers. Impressionable young people. Boteach has his scholarly finger on the pulse of the nation. And at a time when Americans appear to be embracing religion (in one recent poll, 45 percent of teens said their religious beliefs are "very important" to them), he also has a ready-made audience.

So what are all these listeners hearing? Boteach has made sure to offer something for everyone, and it's all connected by one impulse: to appeal to the spiritual seeker by putting the rosiest glow on even the most severe of Jewish laws.

His "Dating Secrets of the Ten Commandments" sounds more like chummy advice than the divine "shalts" and "shalt nots" of the original Ten. In a chapter on the Seventh Commandment (the one prohibiting adultery), for instance, we get tips on "preserving your mystique" and "look[ing] intently at your date." But you can rest assured that behind the sympathetic tone, there are some pretty strong strictures, and they're written in stone.

"It is our hope that by engaging individuals in matters of the soul," L'Chaim's mission statement reads, "we can bring them to understand that there are standards by which man should live." It's a vague statement -- what standards? -- that soft-peddles the thorny Jewish precepts that might make Boteach unpopular among the secularized, liberal audiences he's trying to attract.

For example, Boteach paints a halo around the traditional woman's role while proclaiming his feminist ideals. He has said he believes that "women can be everything men are, and more," but deplores what he calls the "masculinization of women" and suggests that women's "nurturing, healing warmth" is best suited to keeping the home fires burning. His defense of feminine modesty, mandated by Jewish law, echoes that of last year's media darling, Wendy Shalit: That which seduces must be kept private. In an interview he announced that women "do not serve in overtly public roles in Orthodox Judaism because God has given them the beautiful gift of the feminine mystique that makes them the object of male desire." And as Boteach told one synagogue group, according to Jewish law, "women aren't allowed to sing [in public] because the voice arouses. What a beautiful concept!"

In a single chapter Boteach condones some sexual exploration, then explains that Judaism "insists that amid the various experimental sexual positions, there should be one principal position." (Can you guess which one?) And when it comes to masturbation, he doesn't invoke the biblical Onan to back up the prohibition. Rather, he cautions that when a man masturbates, "it has grave consequences for his marriage." (The logic is that if he masturbates, he won't be sexually dependent on his wife, so a special bond will be lost.)

As for homosexuality, Boteach's readers will find no mention of "sin" or "abomination" here. Instead, he voices the vague expectation that with sufficient godliness, the practice will simply wither away: "In the godly system, the disparate parts come together to form the greater whole," he said in an interview. "Men and women create life through marriage. Homosexuality is dismissed in favor of heterosexuality. Sameness is said to be lower on the rung than difference." A few more rules to watch for when you're trying on Boteach's sex code for size: pornography out, S&M out and lights ... out.

Where did this unlikely love prophet come from? Lubavitch, the subculture that produced him, is one of the largest international Orthodox communities in the world. Headquartered in Crown Heights in Brooklyn, N.Y., Lubavitch has since World War II run aggressive outreach campaigns directed at Jews throughout the world, sending thousands of emissaries to revive Judaism everywhere from Azerbaijan to Zaire. In 1989, Boteach was one of them.

Residents of major U.S. cities may have seen these missionaries on the streets, young bearded men in suits and hats who ask dark-haired passersby, "Are you Jewish?" and then, if the answer is affirmative, hand out a Chanukah menorah or some other paraphernalia of Jewish observance. Some areas are blessed with a large recreational vehicle, labeled the "Mitzvah Mobile," that barrels down the street, its P.A. system blaring, inviting Jews to participate in religious life. (A "mitzvah" in Hebrew is a good deed, more literally a commandment.) Lubavitch has outposts on many college campuses as well as in the farthest reaches of the globe.

What the group is promoting is the most strict observance of Jewish law, but as in the case of Boteach, the sell is soft, at least at first. Unlike many other ultrareligious communities, Lubavitch Jews welcome strangers into the fold. So you've never kept kosher? Don't be ashamed. Lubavitch will teach you. Not sure you want to be religious? Don't worry. Just light one candle. Outsiders are often invited to celebrations in the tightknit community, as opportunities to experience the bliss of a Sabbath without work or to observe the blessings of a Lubavitch family.

It's all a way of easing the initiate into Orthodox practice. Lubavitch respects how hard it might be to adopt all 613 commandments that make up the basis of Jewish law, and it's understood that you can take a good long time to learn them. But the group's tolerance does have its limits, as new members gradually learn. You can't take forever to get into full compliance, and you can't pick and choose which commandments to obey. Eventually, you'll have to shape up. As one spokesman said, "We must reach everyone, no matter how far an individual may have strayed, and awaken their inherent connection to the Torah, which God, in his infinite kindness, endowed and entrusted us with as a blueprint for life. It would be gravely misleading to 'change' it, to 'water it down,' for the sake of expedience, for it is not ours to alter."

Twelve years ago, when Boteach was 21 and his pregnant wife 19, he was sent to Oxford to recruit secular Jews to the Orthodox way. Boteach, however, has taken Lubavitch's strategic openness to another level. He stands on no clerical ceremony. He has dispensed with the modesty of his Lubavitch peers, and as a result of his iconoclasm he has been rejected by his community as well. It also seems that he has lost the moral authority to bring the Jews he attracts into compliance with Jewish law.

The 23-year-old president of Boteach's outreach organization (it's a volunteer position), Arash Farin, says he feels no pressure to conform to the Orthodox standards Boteach lives by. The rabbi, he says, encourages him to date Jewish girls, but "he doesn't tell you how to live."

Farin speaks almost proudly about this, highlighting the basic contradiction of Boteach's position. The rabbi long ago recognized the spiritual strivings of a population raised on individuality and self-determination. He also recognized his own ability to bend their ears, to transform the imperatives of Orthodox Judaism into a recipe for personal growth that they could swallow. In part he learned this from his Lubavitch mentors; in part he has gone his own way.

In a quiet moment Boteach tells me, "My professional split from Lubavitch was extremely painful and continues to be so, because of my love for Lubavitch. It's like I'm a man without a community."

And he is. He lives his Orthodox life among the secular, trying to lead his secular followers to Orthodoxy. If he takes the hard line, he's likely to lose them. And if he takes the soft line, it doesn't do much for his belief that Halakha, Jewish law, is "the truth for the Jew." "He doesn't tell you how to live," said the young president of Boteach's organization, praising the rabbi for his restraint. But then, one wonders, what does he do?

Shares